EDUCTION IN THE SOUTHERN MOUNTAINS:

|

| * |

| Pages # |

I.D.#

edu_so_mt_ |

Description |

Thumbnail |

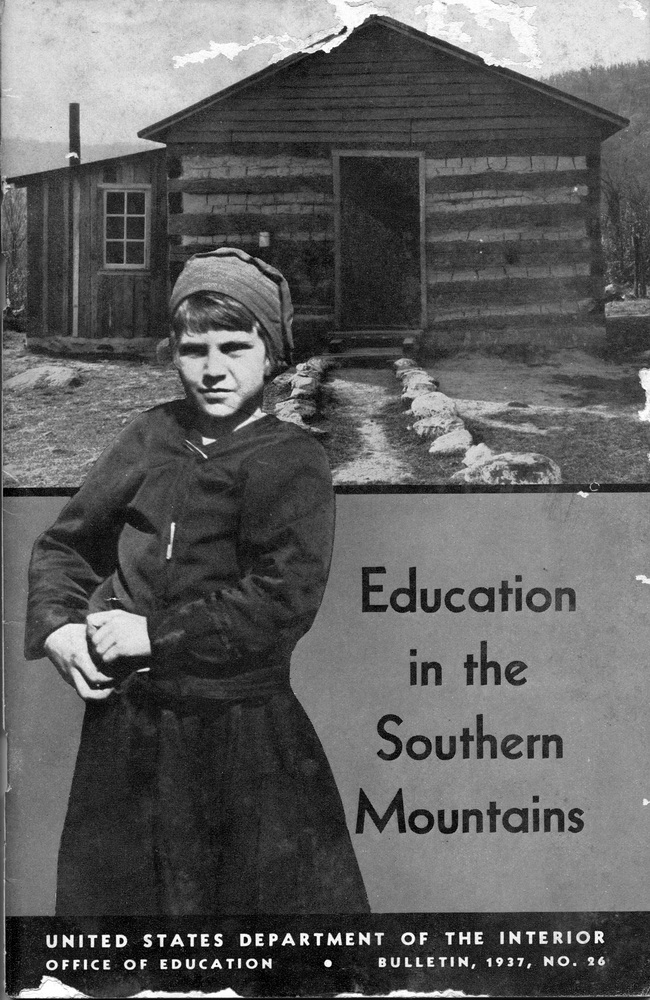

| cover |

cover |

[Cover] Education in the Southern Mountains

United States Department of the Interior

Department of Education

Bulletin 1937, No. 27 |

|

| Foreward |

|

FOREWORD The mountain area of the Southern

States has recently aroused unwonted attention on the part of the people

of the United States. That economic conditions were unsatisfactory; that

social services, including education, were wholly inadequate; and that

these conditions, with the isolation prevalent in mountain sections,

combined to set the people of these areas apart from normal farming

communities, has long been a matter of common knowledge.

Definite undertakings looking toward rehabilitation on a region-wide

scale were not, however, until recently, seriously contemplated. The

Federal Government, in the establishment and maintenance of the

Tennessee Valley Authority, has now entered the region with plans for

reconstruction of at least a large part of the area on an extensive

scale. Interest in education, as perhaps the most important of the

social services so long inadequate, motivated this study of educational

conditions in the area. It is believed it will serve a useful purpose in

furthering plans for continuing the improvements in social conditions,

now so auspiciously begun, through providing authentic information not

hitherto available.

Bess Goodykoontz,

Assistant Commissioner of Education. |

|

| Title page |

|

[Title page] U.S. DEPT. OF

THE INTERIOR, Harold L. Ickes. Secretary

OFFICE OF EDUCATION. J.W. Studebaker, Commissioner

Education

in the

Southern Mountains

Prepared by

W.H. Gaumnitz,

Senior Specialist in Rural Education Problems

Revised and edited by

Mrs. Katherine M. Cook,

Chief division of Special Problems

BULLETIN 1937, NO. 26

U.S. GPO, WASHINGTON, DC 1938

price 15 cents |

|

| Contents |

|

CONTENTS

PageForeword____________________________________________

Chapter I. Introduction____________________________________________ 1

The Southern Highlands—A favorite theme of news and fiction

1

Extent and character of the Southern Highlands ____________

3

Ability to support schools_____________________________ 4

Social and economic conditions________________________

6

Chapter II. School Conditions in the Southern Appalachians_________ 9

Plan of the study____________________________________ 9

The educational problem in terms of numbers_______________

12

Availability and accessibility of schools—A general view_______

14

Proportion of children attending school____________________

14

Elementary and secondary school enrollments_______________ 15

Area per school in square miles and transportation

expenditures. ___ 17

Some measures of the amount and quality of

schooling ___ 19

Grade levels attained_________________________________ 19

Length of school term and days attended_______________________ 21

Illiteracy__________________________________________ 21

Age-grade status of pupils_________________________________ 22

Qualifications of teachers______________________________ 24

Financial measures of educational opportunities

27

Average annual expenditures_______________________________ 27

Value of buildings, grounds, and school equipment_______________ 29

Estimated taxable wealth available for the support of schools_______

32

Financial aid for schools from State sources_______________

32

Human resources as a factor in school support________ _________ 34

Availability of schools in selected mountain

counties 36

Plan and purpose of this phase of the study__ __________________ 36

Location and distribution of schools__________________________ 38

Distances children live from school___________________________ 40

Relationship of school attendance to availability___ ______________45

Chapter III. Denominational and Independent Nonpublic

Schools. 47

Introductory statement________________________________ 47

Types of nonpublic schools_________ ___________________ 47

Curricular offerings_______________________________________49

Nonschool educational activities_________________________ 50

FIGURES

I. Location and expanse of the Southern Appalachian Mountains and

the counties selected for special study

_ 3

II. Location and accessibility of schools, 1932, Lumpkin County, Ga_

37

III. Wolfe County, Ky___________________________________ 39

IV. Macon County, N. C_________________________________ 40

V. Monroe County, Tenn ______________

41

VI. Mercer County, W. Va____________________________ 43 |

|

| 01 |

001 |

EDUCATION IN THE SOUTHERN

MOUNTAINS

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

The Southern Highlands— A Favorite Theme of News and Fiction

According to an author and

student of mountain life, there is no section of our country of which

there is "so much known that is not true" as of the Southern Appalachian

Mountain regions. Much of what is "known" about the southern hill

country, its inhabitants, and their education, is derived from fiction

and colorful newspaper and magazine articles. In order to captivate the

interests of the public or to arouse a desire to do something about

prevalent conditions, writers dealing with such problems naturally

portray the unusual and the extreme. The discovery in 1929, for example,

of an isolated mountain community in which educational opportunities

were still undeveloped suddenly became the subject of picturesque

accounts spread far and wide by press and rostrum. Yet school conditions

for the county as a whole of which this particular hill community was a

part, were generally good. The people of the United States have drawn

from such sources and episodes the general and often mistaken idea that

the conditions portrayed in these unusual localities are typical of the

southern mountains as a whole.

A mountain worker recently voiced his complaint of

this mistaken attitude toward this area as follows:

For many years the southern mountaineer has been the butt of much

highbrow ridicule. He has been scandalously misrepresented and often

shamefully maligned. There are two main reasons for this treatment.

What the outside world has known about us in the past has been

gained from reading books and magazine articles whose scenes are

laid in our mountains. The writers of these books have painted the

mountain people as being feudists and moonshiners ; as ignorant

people living in fearful squalor and degradation; as descendants of

criminals in whose bloody footsteps they still follow; as

ignoramuses who resent the least appearance of anything

|

|

| 02 |

002 |

modern. Mountain books, short stories, novels,

pictures, plays, and collections of ballads galore have recently

appeared—nearly all of which are of an unsympathetic nature. The authors

of these productions chose to write about exceptional and isolated

cases, or imaginary cases, and brand them, without warrant or excuse, as

typical mountain conditions.[1]

Although fully recognizing the tendency of popular writers to depict the

extreme and thus to overdraw the picture, it is, nevertheless, true

that school conditions in the southern mountains constitute a difficult

problem. Reliable accounts of the type quoted below, calling attention

to the neglect and failure to bring educational opportunities worthy of

the term to such communities, could be multiplied:

Unattractive and uninviting though this bleak little school building

may be, to the mountain folk it brings a contact with the outside.

Within, the barrenness was somewhat dispelled by bright pictures

adorning the walls. But even their cheerfulness could not conceal or

counteract the meagerness of furnishings and equipment; no teacher's

desk or chair, no shelf or drawer for books and supplies, five desks for

some score of children, four rough benches (one serving as teacher's

chair and desk), a blackboard limited to one wall, a map of the world

(Mercator's projection), a defective stove, a water pail, and a wash

basin.[2]

* * * Those of us who are working in schools on the secondary level

appreciate the reasons that have caused our boys and girls to be poorly

prepared for the work of the standard high school. We know that in

literally thousands of the one-room schools throughout the mountain

counties the children do not have textbooks. In Kentucky alone 30

percent of the boys and girls in the rural schools last year were

without textbooks; in many schools not more than 10 percent were

provided with schoolbooks. In these same schools there are no

supplementary readers, no charts, no maps, no material for educational

seatwork. The blackboards are so slick one can scarcely make a mark with

a piece of chalk, and pieces of old felt hats are still used for

erasers. Under such conditions we find great soul hunger and little food

with which to satisfy that hunger. It is perfectly apparent that boys

and girls, whose educational opportunities have been such as these, have

not had a fair start in life. Their retardation is easily understood.

Those of us who work in these schools, those of us who have studied

the educational problems of this section in comparison with those of

other sections know that in the mountain counties boys and girls do not

enjoy equal educational opportunities.[3]

[1]

[2]Hitch, Margaret.

Life in the Blue Ridge Hollow. Journal of Geography, 30:

309-323, November 1931

[3] Baird, W. J.

Education. Mountain Life and Work, vol. IX, no. 2, July

1933.

|

|

| 03 |

003 |

Extent and Character of the Southern Highlands

The area designated as the Southern Mountains is composed of a variety

of communities. The region recognized in a recent social and economic

survey of the Department of Agriculture[1]

as the Southern Mountain area and considered in this bulletin, embraces.

[MAP]

205 counties. It lies within six States- Georgia, Kentucky, North

Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia. (See fig. 1.) Smaller

sections of Maryland, South Carolina, and Alabama are frequently classed

as belonging to this general area but these units are not included in

this study. The total area comprises 55,375,580 acres. It is larger by

far than any of the six States of which the Southern Mountains are a

part and is greater in area by 13,000,000

[1]

Economic and Social Problems and Conditions of the Southern

Appalachians. Washington, U. S. Department of Agriculture,

1935. (Miscellaneous Publication No. 205.) pp. 1-2.

|

|

| 04 |

004 |

acres than all the New England States

combined. Its greatest length is about 500 miles; its greatest width 200

miles. The total area has a population of nearly 5,000,000. As a whole

the region is sparsely populated. Low population density, as will be

seen later, is one of the chief difficulties to be met in providing such

social services as public education. While sparsity of population is

characteristic of the area there are two cities, namely, Chattanooga and

Knoxville in Tennessee, each with more than 100,000 population. Six

other cities, namely, Clarksburg and Charleston in West Virginia,

Roanoke in Virginia, Asheville in North Carolina, Johnson City in

Tennessee, and Ashland in Kentucky, have populations ranging between

25,000 and 100,000. There are several other cities such as

Charlottesville and Bristol in Virginia; Bluefield, Fairmont, and

Morgantown in West Virginia; and Rome in Georgia, each of which has a

population of more than 15,000. Moreover, there are within the area

county seats and minor industrial centers with populations ranging

between 2,500 and 15,000. In the urban centers the educational services

and facilities are as a rule as well developed as in other urban

communities of the Nation.

Ability to Support Schools

In many communities in the more sparsely settled mountainous

sections, facilities for public education are inadequate or entirely

lacking. In large parts of the area the farms are extremely small. In

1930 almost one-half of the farms in this highland region were less than

50 acres in area. Fully one-third were less than 20 acres. Their size,

lack of fertility, hillside location, and eroded condition make for low

incomes.

Data are available from a variety of sources showing the prevailing

situation. The Department of Agriculture survey states:

On more than 50 percent of the 383,870 farms, the farm value of all

farm products sold, traded, or used by the farmer's family was under

$600 per farm; on about 30 percent the value per farm was under $400. In

about 18 percent of the minor civil divisions comprising the Southern

Highlands the average value of the farm products traded or sold was

under $200 and in about 3 percent it was under $100 per farm.5

The amount given represents the gross production of the farms

studied. More than 40 percent of the farms in the region were

classified as self-sufficing, meaning that the value of the products

used directly by the farm family was equal to or greater than the value

of all crops, livestock products, forest products, or other farm

products sold or traded during the year. In other words, on two out of

every

s Ibid. p. 41.

|

|

| 05 |

005 |

five farms all of the commodities produced were

necessary to supply the immediate needs of the family, leaving no cash

with which to purchase the "all else"

[1] so essential to a good

life. Moreover, the products available are so limited in variety, if not

in quantity, as to afford subsistence farm families only a low standard

of living. Table 1 shows the average income of farmers of the mountain

counties compared with that of all counties within the respective

States. If certain mountain counties were separated from the group

average for comparison, the value of production per farm would be even

less. According to a study of a group of representative mountain

families in Kentucky, "the total cash income * * * amounted to less than

$45 per family * * * the average dwelling house was worth $110 and the

entire capital, including land, buildings, livestock, tools, and other

items of equipment was $551.[2]

follows:[1]

[TABLE]

In our immediate sections the average (annual) income of the small

farmer is between $85 and $90. The farmer has, of course, his garden and

his land from which he gets most of his living, but $90 does not offer

much margin for taxes, clothes, books, education, seeds, fertilizer,

etc. For a single trip from the county seat we pay the doctor $7. * * *

The topography and history of the mountain country explain why over

large areas our elementary schools have been very poor. While they are

improving greatly,

[1]

Campbell, Mrs. Olive D. Adjustment to rural industrial change with

special reference to mountain areas. Proceedings of the

National Education Association, 67: 484-88, 1929.

|

|

| 06 |

006 |

they are still very inadequate. As a result we have a

large population which, if not actually illiterate, is very limited in

education. This population presents a special educational problem of

which we hear much, and which must always be considered, but which

cannot be considered apart from the economic and social phases of

poverty * * *. Evidence presented later in this study indicates

that the taxable wealth on which schools draw in large part for support

is less adequate in mountain than in the nonmountain areas (see p. 32)

of the same States. A number of studies comparing State tax resources

indicate that the Southern States[1]

which include the mountain area are generally less able economically to

support schools than those in certain other sections of the country.

Since both local and State sources of income are inadequate as compared

with other areas, the mountain

[IMAGE]

Home on the Road to Old Rag, Virginia

section appears to have a double handicap from the point

of view of school support.

Social and Economic Conditions

The causes of backward social and economic conditions in the southern

mountain areas have been discussed widely by many authors and need not

be considered at length here. Conditions have been rapidly changing

during the last 25 years. Improved

[1]

Financing public education, Washington, National Education Association,

1937. (Research Bulletin, vol. XV, No. 1.) |

|

| 07 |

007 |

schools, public and private; roads; hospitals; telephone

and telegraph lines; electric lighting; and modern home conveniences are

among the influences now overcoming isolation and social backwardness.

The program and activities of the Tennessee Valley Authority 10 have

recently given encouragement to the people of the southern mountains.

Efforts are being made through its Division of Social and Economic

Development to study the resources of the area, develop its

potentialities, and plan a program of action. This program is designed

to improve the general social and economic welfare of this section of

the Nation, as well as to exclude from cultivation the portions

undesirable for the maintenance of homes and community life. The effects

of these changes upon education should be significant.

In an intensive study of 428 representative families living in the

mountain areas of eastern Tennessee, eastern Kentucky, and western

[IMAGE]

Home of family of 10 which has been on relief for 18

months.

North Carolina, Prof. Lester R. Wheeler

[1] gathered data showing

changes during the past 25 years in the home, community, and economic

life of the southern mountaineer. He concluded that during these years

the average mountain family has decreased in size from

i° Meyer, Walter E.

The Tennessee Valley looks to the future. Journal of the National

Education Association, 23: 233-48, December 1934.

[1]

Wheeler, Lester R. A study of the remote mountain people of the

Tennessee Valley. Journal of the Tennessee Academy of Science, 20:

January 1935.

|

|

| 08 |

008 |

about 10 members to 8; that the average mountain home

has changed from a "one-room and lean-to-structure'' to a two-story,

frame building of five rooms; that the very limited stock of home-made

furnishings has been replaced by factory-made furniture, including a

sewing machine, a victrola, and a clock; that in every 100 families the

number of home owners has increased by 4, the number of renters has

increased by 6, and the number of squatters has decreased by 10; in

place of one cow per family which constituted the average possession in

livestock in 1910, practically every family now has two cows, a hog or

two, and several chickens; wagons and trucks have largely supplanted the

wooden slip-drags and the horse and the automobile have to a large

extent supplanted travel on foot. Where travel by train was practically

unknown 25 years ago, 67 percent of the mountain people now report

having ridden on a train. The influence of more and better schools is

seen in the increase of the family library from the Bible and an almanac

in 1910 to 32 volumes, a weekly or monthly magazine, a fountain pen and

ink in 1935; improvements were also noted in such basic things as home

sanitation, the place of women in society, and the general standards of

living. The study summarizes the situation by pointing out that the

social and economic status of the average mountain home of 25 years ago

closely resembled the lower 10 percent of those found in that region

today. It appears probable, therefore, that the extreme conditions

commonly depicted by the literature dealing with the southern mountains

represent accurately only the lower 10 percent (according to the author

just quoted) of the homes and communities of this region and not the

average. However, this estimated percentage involves a large number of

boys and girls for whom the presence or absence of an opportunity for an

education is a matter of real importance. It is the purpose of this

study to present data to show educational conditions both in the more

backward mountain communities and in the southern mountain regions

generally. |

|

| 09 |

009 |

CHAPTER II

SCHOOL CONDITIONS IN THE

SOUTHERN APPALACHIANS

Plan of the Study

This chapter presents the following information concerning

educational conditions and efficiency of the school systems: (1) The

average educational practices in the five counties of each State which

are generally regarded the most mountainous and consequently present the

greatest difficulties in the development of public education; (2) the

average educational practices in five representative counties in the

non-mountainous area of each State; (3) the average educational

practices in all of the counties of each of the States commonly regarded

as forming a part of the Southern Appalachian area; and (4) the average

educational practices in each State as a whole. It is apparent that the

total mountain region of each State contains all gradations of

mountainousness and that the averages for the total mountain counties

will include the data for the most mountainous counties. Also the

averages for the States as wholes include both the most mountainous and

the non-mountainous counties.

A comparison of conditions among type areas in each State will

indicate the extent to which mountain conditions have retarded

educational developments. The comparisons will, of course, not be as

sharp nor will the differences be as great when the measures are reduced

to averages for groups of counties as if data for each county were

presented separately.

The statistics in this section were gathered in part from the

published reports and files of the six State departments of education

which exercise jurisdiction over the schools of the area. In some cases

statistical adjustments in the data available were essential in order to

secure comparability. In a few instances, additional data were gathered

directly from the schools.

The data employed are for the most part for the school year 1929-30

and pre-date the period of the depression. However, other studies of

educational changes indicate that the scaling down of such public

services as education has been fairly proportional between mountain and

non-mountain communities, the poorer school districts suffering somewhat

greater reductions. The differences between the educational situations

in 1929-30 and now are not, therefore, as great as one might |

|

| 10 |

010 |

expect. Ordinarily school conditions do not vary greatly

from year to year. The 1929-30 data have the advantage of being

comparable to the data published by the United States Census Report, a

source frequently drawn upon in this study. (The data deal with

educational conditions among white persons unless otherwise indicated.)

Scope and Setting of Survey.—The names of the entire group of

mountain counties as well as those of the counties selected to represent

the most mountainous and the non-mountainous sections are as follows:

[TABLE] |

|

| 11 |

011 |

[TABLE] The counties constituting the total

mountain area included in this study are marked out with a heavy broken

line on a map of the southeastern quarter of the United States. (See

fig. I.) On this map are shown, through distinctive hatchings, the

location of the five counties selected to represent the most mountainous

sections, as well as the five counties selected to represent the

non-mountainous areas of each State. The former were selected from a

group ranked by school officials from each State as areas which are most

mountainous and in which mountain conditions definitely influenced

educational development. The latter were selected at random, care being

taken that one county in each State contained one of the larger urban

centers and that all non-mountain sections of each State were

represented.

The six States with which this study is concerned constitute an area

of 253,617 square miles (see table 2), 85,356 of which are included in

the area known as the Southern Highlands. About two-thirds of this area

is in three of the States—West Virginia, Virginia, and Tennessee.

The area within the Tennessee Valley Authority is outlined in figure

I. It includes 23,477 square miles, or 27.5 percent of the total

Southern Highlands. More than three-fourths of the mountain section of

Tennessee and about one-half of that of North Carolina are included

under the Valley Authority. |

|

| 12 |

012 |

[TABLE] THE

EDUCATIONAL PROBLEM IN TERMS OF NUMBERS

The first aspect of

education in the southern mountains to be examined here concerns the

number of children of school age living within the area. The age groups

as given in the table roughly correspond to the periods of elementary

and secondary education. (See table 3.) In the 205 mountain counties of

the six States, slightly more than a million children 7 to 15 years of

age and somewhat fewer than half a million of those 16 to 20 years of

age live. From the standpoint of potential school attendance,

therefore, approximately a million and a half boys and girls are

involved—nearly 40 percent of the children of the designated age groups

in the six States. About half as many children of school age live in the

most mountainous as in the non-mountain counties. The differences are

particularly marked in Georgia and in Tennessee.

The

data presented in table 3 show also the distribution of the youth by age

groups in the mountainous and non-mountainous sections of these States.

The proportion of children 16-20 years of age to the total group is

considerably greater in the latter than in the former, the differences

being greatest in Tennessee and least in Virginia. This indicates the

tendency of older children to forsake the mountain communities to find

homes and occupations elsewhere. The differential is not affected by

persons attending schools away from home because the children were

enumerated where they reside rather than where they attend school. The

general tendency for children of the post- |

|

| 13 |

013 |

elementary school ages to leave the mountain communities

is more evident when the factor of sparsity is considered than when

population data only are compared. (See table 4.) The natural sparsity

of population in the mountain counties and the tendency of the children

to leave home early together constitute one of the chief difficulties in

making suitable school facilities available, particularly for

secondary-school children. Of course it is possible that if better

educational opportunities were accessible, the mountain child

[TABLE]

would not leave home so early. |

|

| 14 |

014 |

Availability and Accessibility of Schools—A General

View Perhaps the most important consideration relating to school

conditions in the southern mountains is the question of whether or not

there are schools available within reasonable distances of the

children's homes. The factors involved in this question are many and

complex.[1]

Comprehensive information concerned with school accessibility is not

available. Data which provide certain significant indices are, however,

presented as indicative of the situation. They concern the proportion of

children of school age enrolled in school; the comparative enrollments

in the elementary and secondary grades; the average number of square

miles per elementary and per secondary school; and the per-pupil

expenditure for transportation.

Proportion of children attending school.—The proportion of children

of school age enrolled in school is considered a practical measure of

school availability. If the proportions in each of the several age

groups compare favorably with those in other communities, it may be

assumed that schools are available. However, evidence of enrollment

does not necessarily mean that the schools are readily accessible or

that the children attend regularly. In table 5 data are presented

showing percentages of persons attending school in the several types of

areas for the age groups 7-15, 16-20, and 21 years and over,

corresponding roughly to the periods commonly associated with the

elementary school, the high school plus junior college, and college

plus any organized efforts in the field of adult education,

respectively. In order to get an index of school enrollment for the

entire school age group, the total number of children 7-15 years of age

and those 16-20 years of age were combined and percentages found for the

proportion reported to have been in school in each type of community

studied.

These data indicate that of the children 7 to 15 years of age, the

period most closely affected by the compulsory attendance laws,[2]

from 5.7 to 19.7 percent failed to attend school during the school year

indicated. For the counties representing the most mountainous sections

of these States, the proportions not enrolled in school ran consistently

higher than those of the representative nonmountain counties of the same

States. In the mountain counties of Kentucky, nearly one of every five

children of elementary school age failed to enroll in school; attendance

in the nonmountain counties of this State was 12.6 percent higher than

the average for the mountain

[1]

Cook, Katherine M., and Gaumnitz, W. H. Availability of schools in

rural communities. In the Status of Rural Education. Bloomington,

111., Public School Publishing Co., 1931. (National Society for the

Study of Education, 30th Yearbook, Part I.)

Gaumnitz, W. H. Availability of public-school

education in rural communities. Washington, Government Printing

Office, 1931. (U. S. Department of the Interior, Office of

Education, Bulletin 1930, No. 34.)

[2]

The compulsory laws of Kentucky, Tennessee, and West Virginia

require the attendance at school of all children 7-16 years of age;

Virginia, 7-15; North Carolina, 7-14; and Georgia, 8-14.

|

|

| 15 |

015 |

counties, closely paralleling the percentages in the

same age group in the non-mountain sections of the other five States

studied. The non-attendance was more than 10 percent in the most

mountainous counties of all of the States except West Virginia.

[TABLE]

Of the children 16-20 years of age in the mountain sections of the

several States, approximately two-thirds did not attend school during

the period. This compares fairly closely with percentages found for

these Southern States as wholes, as well as with percentages for the

entire Nation. But when the percentages for the most mountainous and the

non-mountainous counties are compared, substantial differentials may

again be noted in favor of the latter, West Virginia again providing the

exception. Among persons more than 20 years of age, the percentages show

relatively small differences among the various types of areas.

The differences between the percentages for the most mountainous and

nonmountainous sections of the various States are less marked among

older children. They are no doubt able to walk greater distances. Those

going to colleges no longer travel daily the distance from home to

school. Moreover, some of the schools for pupils of high-school age are

boarding schools, especially in the more mountainous sections. Private

and philanthropic enterprises make a great effort to bring older persons

from the more backward communities into contact with educational

opportunities.

Elementary and secondary school enrollments.—Accessibility should

|

|

| 16 |

016 |

be considered also

from the standpoint of the grade level attained. Data presented in table

6 show that only a small proportion of children of the more mountainous

sections are enrolled in high school. While

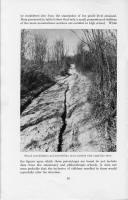

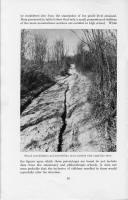

[IMAGE]

School consolidation and accessibility

must contend with roads like these.

the figures upon which these percentages are based do not include

data from the missionary and philanthropic schools, it does not seem

probable that the inclusion of children enrolled in them would

materially alter the situation |

|

| 17 |

017 |

In every State the non-mountain counties show much

larger percentages of the entire public-school enrollments attending

high school than the mountain counties. If all the children old enough

to attend the last 4 years of the public schools were enrolled in these

grades, the percentage should approximate 30. That this percentage is

seldom reached is indicated by the fact that the Nation's schools as a

whole average only 17.1 In city school systems it tends to approach more

closely the maximum than in rural communities. This fact accounts

largely for the 30.6 percent of the school population found in high

school in the non-mountain counties of Georgia. Fulton County, Ga.,

contains the city of Atlanta, in which enrollment in high school is high

compared to that in other areas of the State. Comparatively few of the

children in school in the most mountainous

[TABLE]

counties, particularly in Georgia, Kentucky, or Virginia, attend

high school, unless they go to nonpublic schools or schools outside of

their home counties. Opportunities for secondary education are probably

not available in the home counties. While fairly high percentages of

those 16 to 20 years of age are attending school (see table 5), many are

evidently still in the grades, and are either marking time because no

high schools are available or are retarded.

Area per school in square miles and transportation expenditures.—

Further evidence that the opportunity to obtain a secondary school

education at public expense is not generally provided in the most

mountainous sections of these States may be found in the data showing

the average area per high school (see table 7). It seems reasonable to |

|

| 18 |

018 |

assume that, barring the use of boarding and

transportation facilities as means of overcoming distance from school,

the average area served by the secondary school of a given community

should not be much greater than the area served by the elementary

school. The areas per elementary school are, therefore, likely to

represent closely the maximum attendance areas of the high schools. It

may be noted (see table 8) that in the mountain counties comparatively

little money is spent for pupil transportation, thus indicating that the

accessibility of the schools provided is not materially improved through

this means. And, so far as is known, provisions are seldom made from

public funds to pay the board of pupils who attend high school away from

home. If, therefore, the basic assumption is granted, it is clear from

the data presented that comparatively wide areas of the most mountainous

counties

[TABLE]

are not within reach of schools offering high school work. |

|

| 19 |

019 |

than in the mountain counties of these States. However,

the non-mountain counties in these States show unusually large

expenditures for pupil transportation. In the other three States the

average areas vary comparatively little for all schools. The area per

high school is, however, considerably greater for the mountain counties

of all six States than for the nonmountain counties. In Kentucky and

Tennessee the average area per high school is nearly twice and in

Georgia more than three times as great in the most mountainous counties

as in the nonmountain counties. Even if the secondary schools were

centrally located and if the children could travel to and from such

schools in a direct line "as the crow flies", those living farthest away

would obviously have to travel long distances to school. In the most

mountainous counties of Georgia, for example, the distance might be more

than 6/2 miles each way. High schools in the mountain counties are as a

rule in villages not often located in the geographical center of the

respective counties. Moreover, the more mountainous the area, the more

likely it is that a given point can be reached only by a circuitous

route. Although the data presented thus far are somewhat general and

indirect in character, they indicate that public schools, especially

high schools, are not as available in the mountain as in the nonmountain

areas of the States in question and that inaccessibility is more serious

in the most mountainous counties. It also appears that many children of

high-school age attending school are still in the elementary grades.

Some Measures of the Amount and Quality of Schooling

Grade levels attained.—Table 9 presents data concerned with the grade

levels to which the children in the different types of areas are

retained in school. Taking the third grade as representing 100 percent

attendance, percentages were computed which show the extent to which the

children are still in school when the sixth grade, the first year of

high school, and the last year of high school, respectively, are

reached. The third grade is used as a basis because, by the time the

child reaches this grade, he is normally 8 or 9 years of age. He is old

enough to withstand the hardships entailed in traveling reasonable

distances to school and not old enough to be kept home for work or to

stay away from school because he thinks himself too grown up to attend.

The data indicate that there are about two-fifths as many pupils in

the sixth grade of the schools of the most mountainous counties of

Kentucky as in the third grade. In the non-mountain counties of the

State fully two-thirds of the pupils are retained to the sixth grade. |

|

| 20 |

020 |

In Tennessee and Virginia also the percentages of pupils retained to the

sixth grade are higher in the non-mountain counties. In North Carolina,

however, a larger proportion of pupils of the most mountainous counties

stay in school to the sixth grade than in the non-mountain counties.

Ratios of enrollments in the first year of high school to those in the

third

[TABLE]

grade are higher in the non-mountain counties of all the States.

Indeed, comparisons for both the first and last years of high school

show the effect of mountainousness upon pupil retention. If the data

presented in table 10 are representative, there are whole mountain

counties in the six States in which only about two of five children

receive as much as a sixth-grade education. Even the best of the more

mountainous counties seldom keep more than three-fourths of the children

through this grade. With the exception of West Virginia and North

Carolina, the schools of the more mountainous counties lose at least

three out of every four children before they reach high school and only

one-fourth to one-half of those who enter high school remain until the

last year. The non-mountain counties of these States, other than West

Virginia, retain about twice as many to high-school entrance and hold a

much larger proportion of the children until they reach the fourth year

of the secondary school.

Generally speaking, the schools of each of the six States as a whole

consistently show better records in retaining pupils to the higher

grades |

|

| 21 |

021 |

than the mountain sections. For the high-school levels

the differences are for the most part marked. The highest percentages

retained in school, even in the nonmountain areas, are considerably

below those found for the Nation as a whole. Some States in which the

schools are developed beyond the average would, of course, show

retention indices higher than those for the Nation as a whole.

Length of school term and days attended.—Two indices of the amount of

school education provided in the mountain communities are the number of

days per year schools are open and the number of days the pupils

actually attend school. Data presented in table 10 give information of

the types indicated. They may be read as follows: In the five most

mountainous counties of Georgia the elementary schools are open an

average of 141 days per year; in the five nonmountain counties they are

open 179 days—nearly 2 months longer. In the former the pupils attend on

an average 98 days annually and in the latter 142 days. The actual

period of instruction received by the average child in the most

mountainous counties of Georgia is nearly 9 weeks shorter each year than

in the non-mountain counties. In at least three of the States the

disadvantage of short terms in the most mountainous counties is

aggravated by irregular attendance.Illiteracy.—Two types of

illiteracy data are discussed in this study. (See

[TABLE]

table 11.) The illiteracy of persons 10-20 years of age may be

thought of as the present responsibility of the schools. The illiteracy

of persons older than 20 may be regarded as evidence of the past failure

of the schools. The fact that the percentage of illiterates |

|

| 22 |

022 |

shown for the younger age group is in every case very

much lower than for the older group, indicates that a greater effort is

being made than formerly to achieve some education. [TABLE]

Data for both age groups are favorable to the non-mountain counties.

In the most mountainous counties of Kentucky, Virginia, and Tennessee,

approximately 1 in 20 of the children of school age were reported as

illiterate in 1930; of those over 20 years of age in the most

mountainous counties of 4 States, more than 1 in 10 were unable to read

and write. There is some evidence that the more backward communities are

now improving more rapidly than the non-mountain sections. In any event,

the data presented in table 11 do not show as much illiteracy in the

most mountainous sections as the general reports from these regions

would lead one to expect. Due to the high literacy rate of Fulton

County, containing the city of Atlanta, the non-mountain area of Georgia

is the only type area included in this study in which the illiteracy now

"in the making'' is lower than that of children 10 to 20 years of age

for the Nation as a whole. The non-mountain counties of four of these

States, however, show a smaller percentage of white adult illiterates

than the average for the Nation. In all but one case, the illiteracy

percentages of the six States, taken as wholes, are considerably higher

than those for the Nation.

Age-grade status of pupils.—A measure commonly used as an index of

the effectiveness of schools is the age-grade status of the pupils.

Assuming that a child 6 or 7 years old should be in the first grade, one

7 or 8 years old in the second grade, one 8 or 9 years old in the third

grade, and so on, table 12 shows that the percentages of children |

|

| 23 |

023 |

who are above normal age for their grades are higher in

the most mountainous counties than in the non-mountain counties of the

respective States. Retardation is apparently nearly as great a problem

in the high school as in the elementary grades. No data wholly

comparable are available for the Nation as a whole, but a sample study,

based upon data for 1927 [1]

involving 116,651 white pupils in the elementary grades of 70

representative city schools located in 35 States, showed 13.4 percent

over age; another study made in 1928

[2] of 7,632 pupils in the

elementary grades of 45 representative consolidated schools showed that

15.2 percent of the children were a year or more retarded; still another

study made in 1930,[3]

including both elementary and secondary schools located in the rural

communities of 22 counties of 5 representative States, showed that of

the 52,574 pupils involved, 17.6 percent were 1 or more years retarded.

Table 13 offers additional data concerning retardation. It should be

read as

[TABLE]

follows: 64 percent of the 10-year-old children of the most

mountainous counties of Kentucky are retarded. Of these, 23.6 percent

are retarded 1 year; 21.1 percent, 2 years; and 19.3 percent, 3 or more

years. In the no-nmountain counties of this State, 37.8 percent of the

10-year-old children are retarded; 19.4 percent, 1 year; 10.9 percent, 2

years; and 7.5 percent, 3 years or more. It is significant to

[3]

Gaumnitz, W. H. Availability of public education in rural

communities. Washington, Government Printing Office, 1930. (U.

S. Department of the Interior. Office of Education, Bulletin 1930,

no. 34.)

5 Blose, D. T. An age-grade study of 7,632

elementary pupils in 45 consolidated schools. Washington,

Government Printing Office, 1930. (U. S. Department of the Interior,

Office of Education, Pamphlet No. 8.)

[1]

Blose, D. T., and Segel, David. The school life expectancy of

failures in the elementary grades. American School Board Journal,

March 1933.

|

|

| 24 |

024 |

note that the differences between the percentages for

the two types of communities become greater as the number of years of

retardation increases. The proportion of the children retarded as well

as the number of years they are retarded is considerably greater among

the 14-year-olds than among the 10-year-olds. Not only are larger

proportions of the children retarded as they become older, but the

number of years the average child is retarded increases as he becomes

older. These facts probably account to a considerable degree for the

comparatively small number of pupils shown by table 9 to reach the

upper grades of the school. There is a tendency for retarded children to

become discouraged and leave school. [TABLE]

Qualifications of teachers.—Educators generally agree that the most

important factor in school efficiency is the teacher. Other things being

equal, the teacher most thoroughly trained should be the most

successful. It follows that the quality of the education provided by

the school is to a degree determined by the amount of training the

teachers have received. In order to examine this aspect of the education

provided in the southern mountains, data are presented (see table 14) to

show, first, the proportion of the teachers serving these schools who

have high-school education or less and, second, the proportion who have

2 years or more of college education. Those in the first group are

above |

|

| 25 |

025 |

the level of the general population of these

communities, but inadequately trained for teaching. The second group

have training now widely accepted as a minimum standard for teaching

certificates. [TABLE]

[IMAGE]

Mountain school and teacher's cabin.

With the exception of West Virginia, the differences between the

training of the teachers of the most mountainous counties and of those

of the non-mountain counties are favorable to the latter. (See table

14.) In the most mountainous counties of Georgia and Kentucky, for

example, more than three-fourths of the teachers have a high-school

education or less. In the former, the percentage of teachers |

|

| 26 |

026 |

with this training is more than seven times as great in

the most mountainous counties as in the non-mountain counties. In

Virginia the percentages of such teachers in all types of areas are

smaller than in any of the other States, but in the most mountainous

counties the proportion is nearly six times as great as in the

non-mountain counties. In the non-mountain counties of the States

having the best record in teacher preparation a considerable proportion

of the teachers are comparatively unprepared and nearly one-half fall

below the accepted standard of 2 years of college education. The recent

oversupply of teachers is resulting in raising the certification

standards and consequently in lowering the percentages of undertrained

teachers. While comprehensive comparative data are not available,

progress along this line in the most mountainous counties appears to be

less satisfactory than in the non-mountain counties as indicated in the

table.

Experience is usually also considered an important measure of the

efficiency of teachers. Studies of experience as a factor in teaching

efficiency verify the general observation that especially during the

first 5 years of service in the schools a teacher gains in knowledge and

skill through professional reading, contacts with fellow teachers, and

similar types of experiences. Although the differences are

comparatively small, the percentages (see table 15) show clearly that

in all of the six States, except Virginia, the schools of the most

mountainous counties employ a larger proportion of beginning teachers

than those of the non-mountain counties. Conversely, the non-mountain

counties of all but West Virginia attract and hold a larger proportion

of experienced teachers. A study of 150,182

[1] teachers employed in

1930 in schools located in centers of 2,500 or fewer population in the

United States revealed that 17.4 percent were teaching their first year,

while 68.4 percent had taught 3 or more years. For the most part, the

available data show that stability of the teaching force does not differ

widely in the six States from that in the Nation as a whole. The slight

advantage shown by some of these States in this respect would probably

disappear entirely if, as in the Nation-wide study, data from city

schools were excluded.

Another factor which determines to some degree the quality,

training, and fitness of the persons employed as teachers is the salary

paid. The average annual salaries of teachers and supervisors of the

various types of counties in 1930 are shown in table 16. The average

teacher employed in the most mountainous counties of Georgia was paid

$436 per year; in Kentucky, $510; in Virginia, $588; in North Carolina,

$654; in Tennessee, $716; and in West Virginia, $988. The salaries are

[1] Gaumnitz, W. H. Status of

teachers and principals employed in the rural schools of the United

States. Washington, Government Printing Office, 1932. (U. S. Department

of the Interior, Office of Education, Bulletin, 1932, No. 3.) |

|

| 27 |

027 |

higher in the nonmountain counties in all States. Omitting Georgia, the

differentials range approximately from $250 to $400.

table 15.-— Percent of

teachers new to the profession and those having 3 or more years of

experience, 1930

[TABLE]

financial measures of educational opportunities

Average annual expenditures.—When the educational opportunities

of two or more communities are compared from a financial viewpoint, two

major considerations are: The amount spent annually to support the

public-school program; and the money invested in housing and material

equipment. To secure measures whereby the various groups of counties may

be compared, annual expenditures for the public schools for whites,

except funds invested in new sites, buildings, and equipment, were

totaled by counties and by groups of counties. (See table .17.) These

were then divided (1) by the total number of white teachers employed in

the schools, (2) by the number of white children

|

|

| 28 |

028 |

6-20 years of age living in the respective counties, and (3) by the

number of pupils enrolled in the public schools for whites.

[TABLE]

While each type of divisor

has its own peculiar significance as a measure of the amount and quality

of education provided, the annual per-teacher cost is probably the best

of the three measures of financial support in a given community. It

overcomes somewhat the differences due to sparsity of population. In

one-teacher schools it is roughly equivalent to all the money spent for

school purposes.

The measure of comparative costs most commonly employed in the United

States is the average expenditure per pupil. Since this measure does not

consider the children of school age who live in a given area but are not

attending school, the per-capita costs were computed also on the basis

of all children 6-20 years of age who live in each group of counties as

given by the United States census report. The three types of data are

presented in table 17.

Great variations in public-school expenditures among the States and

between similar types of communities are shown in the table. In each

case, except for the non-mountain group, Georgia shows the lowest annual

expenditure for public education; West Virginia the highest. The schools

of the most mountainous counties of Georgia and Kentucky spent less than

half as much on education as those of |

|

| 29 |

029 |

West Virginia. Insofar as greater expenditures mean

better schools, comparisons between the most mountainous and the

non-mountain counties reveal significant differences in favor of the

latter. The differences in expenditures shown are from 45 percent higher

in West Virginia to nearly 300 percent higher in Georgia. When

comparisons are made to the United States as a whole, even the highest

average expenditure found in these six States falls below the national

average. Value of buildings, grounds, and school equipment.—Data to

show the amount of money per teacher and per child 6-20 years of age

invested in school buildings and sites and in permanent school

equipment are presented in table 18. The value of school property

reported by local school officers is in part estimated. However, it is

believed that the counties in question follow the same method of

determining and reporting the amount of money invested in school

property. The data are therefore assumed to be comparable among the

several States.

[IMAGE]

Certainly they permit comparison between the groups of counties

within each State. In the case of West Virginia separate data for white

and Negro schools were not available for either the value of school

buildings and grounds or for the equipment. Hence the data presented for

this State are for both races. The same is true of equipment values

recorded for Kentucky.

The five most mountainous counties, as well as the mountain counties

as a whole within each State, have apparently invested comparatively

little in school buildings and equipment. If it is assumed that the

averages for the non-mountain counties represent the amount a community

should invest in school buildings and equipment, it may be concluded

that the more mountainous groups of counties fall far short of the

need. In Georgia, for example, the most mountainous |

|

| 30 |

030 |

counties report an

average investment in buildings and grounds of less than $800 per

teacher as compared to more than $5,000 in the non-mountain counties—a

ratio of 1 to 6. In Kentucky the most mountainous counties show an

investment less than one-fourth that of the non-mountain counties. In

Tennessee and West Virginia the difference is less striking. But even in

these States the non-mountain counties have invested nearly 1 % times as

much money in school buildings and grounds per unit of measure as the

most mountainous counties. The entire mountain counties of the several

States, with the exception of Tennessee, show consistent and marked

disparities when the average values of school buildings and grounds are

compared with those of the

[TABLE]

|

|

| 31 |

031 |

States taken as wholes. Compared on the per-child basis,

the differences are greater than on the per-teacher basis. Generally

speaking, both in the value of school buildings and grounds and in the

amount invested in school equipment, the mountain counties fall below

State standards as well as below those maintained in the non-mountain

counties of the respective States. When national averages are taken as

standard, these shortcomings of the mountain schools are still more

apparent. Averages do not, of course, show extreme conditions. In some

communities visited there were no public-school buildings; church

buildings and benches were used for school purposes. Equipment consisted

of the few books and materials the children brought from home or which

were provided through the resourcefulness of the teacher. Many public

schools observed in the remote mountain communities are plain square

buildings in poor repair, containing very little equipment.

Under the local system of financing public education, widely

practiced in the United States, the presence or absence of educational

services, and the conditions of the schools in general, are found to

bear a very close relationship to the wealth of the communities in which

they are located.[1] Since

the economic conditions of the southern mountains are below standard,

the school buildings and equipment provided are also unsatisfactory.

Estimated taxable wealth available for the support of schools.—Some

idea of the differences in taxable wealth among the types of

communities in the States studied may be obtained from table 19,

showing the estimated wealth per teacher employed and per child 7 to 20

years of age. The data include figures for both whites and Negroes.

The differences between the average estimated wealth per teacher for

the most mountainous and the non-mountain counties are for the most part

significant. The differences are somewhat less when computed on a

per-child basis than when computed on a per-teacher basis. A comparison

of the average expenditures and the per capita wealth suggests that the

several groups of mountain counties levy slightly higher taxes for

school purposes than the average of the respective State of which each

is a part. Similar comparisons between these States and the Nation

reveal, however, that school tax rates are somewhat lower in the six

States than in the Nation as a whole.

Financial aid for schools from State sources.—It is of interest in

this connection to note the extent to which schools in the States

studied draw upon State funds to supplement or equalize the funds

available for school purposes from local tax resources. Information is

presented to show the amount of money contributed to the public schools

from State sources computed on the basis of the number of teachers em-

They Don't Pay Taxes. Journal of the National Education Association,

21: 259-61,

[1]

Cowden, Susie E. November 1932.

|

|

| 32 |

032 |

[IMAGE]

[IMAGE] |

|

| 33 |

033 |

ployed and on the basis of the number of children 7-20

years of age living in the various counties. (See table 20.) [TABLE]

In West Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Georgia an effort is

being made through state aid to off-set the limitations of the

[IMAGE]

Abandonment of old clap-board buildings |

|

| 34 |

034 |

mountain counties due to inadequate taxable wealth. In

West Virginia, and probably also in North Carolina, the favorable

differential in State aid enjoyed by the most mountainous counties

fully offsets the unfavorable differential in per-capita wealth. In

Virginia there are comparatively small differences between mountain and

non-mountain communities in estimated taxable wealth. In the other three

States the aids provided from State sources for the schools of the most

mountainous counties do not appear to offset the disparities in their

ability to support schools. In Kentucky, for example, State aid per

capita is, if anything, greater in the non-mountain counties despite the

fact that the per-capita wealth is more than three times as great

[IMAGE]

Replacement by new consolidated schools

as in the five most mountainous counties.

In recent years much progress has been made in the equalization of

the educational opportunities through the use of State funds; West

Virginia, North Carolina, and Tennessee are examples. If comparative

data were available showing State aid in mountain and non-mountain

counties for a date later than here presented, changes in the situation

would probably appear in these States.

Human resources as a factor in school support.—The ratio which the

number of adults 21 years of age and older bears to the number of

children and youth to be educated is sometimes considered as a factor in

a community's ability to support schools. Table 21 shows the |

|

| 35 |

035 |

[TABLE]

|

|

| 36 |

036 |

old, 5.7 adults. In the most mountainous counties,

however, the ratios are 1 child to 1.7 adults for the younger group of

children, and 1 to 4.1 adults for the older group. In the non-mountain

counties of this State there are, therefore, 1.2 and 1.6 adult producers

more per child of elementary school and high-school age, respectively,

than in the mountain counties. Georgia and Tennessee show very similar

disparities. If the effects of this factor on. the inequality in ability

among the various types of counties to support an adequate school

program are added to those previously mentioned, the lack of

educational progress is more easily understood. Rupert B. Vance

[1] points out the

significance of this factor in his study of the relationship of regional

resources and human adequacy when he calls attention to the fact that 11

of the Southern States, with less than one-quarter of the Nation's

population, have fully two-fifths of the Nation's children to rear and

educate. If only the children living on farms are considered, it appears

that the rural areas of these 11 States now rear and educate nearly

two-thirds of all the farm children 5-20 years of age of the United

States.

Availability of Schools in Selected Mountain Counties

Plan and purpose of this phase of the study.—In order to get a

close-up view of the whole question of the accessibility of schools in

the Southern Appalachians, a detailed study was undertaken of a number

of selected mountain counties. Data are here presented in the form of

county maps (see figs. II to VI and tables 22 to 25), which are

supplemented with statistical data collected directly from individual

schools. The five counties named below, with the State in which each

is located, furnished the information necessary for this part of the

study: Lumpkin, Ga.; Wolfe, Ky.; Macon, N. C.; Monroe, Tenn.; and

Mercer, W. Va. These counties may be thought of as fairly typical of the

most mountainous sections of these five States. They represent,

therefore, those parts of the mountain areas in which the problems of

making public educational opportunities readily accessible to all of the

children are the most difficult.

Factual data presented in this section were collected directly from

the schools and the county superintendents of the counties in question.

The purpose is to provide, by way of illustration, answers to the

following questions: Just how many and what kinds of schools are there

in the most mountainous counties? How are they distributed over the area

to be served? How far are the elementary schools from each other? The

high schools? How far do the children live from the

[1]

Vance, Rupert B. Human Geography of the South. University of

North Carolina Press, 1932. (University of North Carolina Social

Study Series.)

|

|

| 37 |

037 |

[MAP]

|

|

| 38 |

038 |

are: The time required and the effort expended in

traveling to and from school. These vary with climate, topography, road

conditions, the age of the child, cooperation of parents and the like.

In surveys of city school systems, the practice followed in certain

recent studies is to fix one-half mile as the maximum distance a child

should walk to school. The maximum distance fixed in studies made by

rural educators and by the compulsory education laws of most of the

States is usually either ll/2 miles or 2 miles. A maximum of 2 miles is

the basis used for purposes of this section. Location and distribution

of schools.—The schools within the five counties were located on the

county maps as accurately as possible, with the help of the county

superintendents, and a circle drawn around each school upon a 2-mile

radius. No home within a given circle is more than 2 miles from the

school located at its center. The actual distance children walk to

school may, of course, be greater. Mountain roads tend to wind in and

out with the valleys and creeks. Precipitous mountains often act as

barriers. Even where there are areas of fairly level country, the route

from home to school will seldom follow a straight line.

The circles placed around the schools, together with the symbols

showing that they serve the elementary or the secondary grades, or both,

will afford some idea of the distances the schools of various types are

from each other. (Figs. II to VI.) The schools are usually located in

valleys and on bottom lands. In areas in which the contour lines are

farthest apart, indicating little change in elevation, the circles

overlap considerably; in areas in which the contour lines are close

together, indicating mountainous terrain, there is comparatively little

overlapping. Indeed, parts of the more mountainous areas are not

included in any of the circles, indicating that such areas are located 2

miles or more from the nearest schools. The small circles, squares, and

other symbols locating the schools, and the numbers within these

symbols, show that almost all of the elementary schools are of the 1-

and 2-teacher type. The high schools usually employ three or more

teachers, indicating that they serve as central schools for several

elementary school districts. In Lumpkin County, Ga., for example, there

is only one high school in the entire county.

Transportation to either the elementary or the secondary schools is

provided in comparatively small portions of these communities. One

reason for the absence of transportation is that roads in the more

mountainous sections are as a rule undeveloped. Where school bus routes

are maintained, peculiar markings have been placed on the maps to

indicate whether they serve the elementary pupils, the high-school

pupils, or both. Lines paralleling the few existing bus routes were also

marked out to show the territory located within 1% miles |

|

| 38 |

039 |

of these routes, the assumption being* that children who

live within 1 ji miles of such routes may be thought of as being

accessible to the schools to which these bus routes lead. Symbols are

used to show white schools, Negro schools, and nonpublic as well as

public schools. Although these circles show that, even in these more

mountainous counties of the Southern Appalachians, the number and

distribution of the schools are such as to place practically all areas

within 2 miles

[MAP]

Figure III: Location and accessibility of Schools,

1932, Wolfe County, Ky.

of some sort of an elementary school, there are areas in each county

which fall outside of these circles. In Lumpkin County, Ga., and Macon

County, N. C, nonschool areas are comparatively numerous and large.

Mercer County, W. Va., on the other hand, has practically no such areas.

The question of whether children of school age live within the areas

outside the circles is very important. If these areas contain no

children they are of little interest to us so far as the problem of the

availability of schools is concerned. Data were gathered directly from

representative schools within these counties to show |

|

| 40 |

040 |

the actual distances the children live from their

schools. Most of the schools furnished information showing the distances

between home and school of both the children attending school (see table

22) and those of school age who are not attending school (see table 23).

It may be assumed that those reported as living more than 2 miles from

school live outside of the circles. The data given in the tables concern

only the children walking to school because provision for transportation

involves changes in the problems of school accessibility. Distances

children live from school.—In each of the five counties there are some

children both in and out of school who live more than

[MAP]

Figure IV: Location and accessibility of schools,

Macon County, 1932, N.C.

Distances children live from school.—In each of the five counties

there are some children both in and out of school who live more than 2

miles from the nearest schools provided. (Table 22.) Of those attending

school in these counties a total of 1,098, or 9.2 percent, live from 2

to 4 miles, and 143, or 1.2 percent, live 4 miles or more from the

school. Of the out-of-school children in the five mountain counties

there are 489 children living from 2 to 4 miles from a school and 48

living 4 miles or more; or in percentages, 30 and 2.9, respectively.

There is good reason to believe that many of the out-of-school children

were not reported by the schools and that the proportions unreported

vary directly with the distances they live from the schools furnishing

the information. If all of the out-of-school children were included |

|

| 41 |

041 |

[MAP]

|

|

| 42 |

042 |

[TABLE]

|

|

| 43 |

043 |

[MAP]

|

|

| 44 |

044 |

children who have at one time or another attended

school, data were secured for a total of 1,630 out-of-school children 5

to 20 years of age. Of these, 1,503 were 13 years of age or older. Most

of them had probably discontinued school. However, as will be seen in

table 25, fewer than half of them had reached the seventh grade before

leaving school; nearly a fourth had not gone beyond the fourth grade.

Nearly one-third of all of these out-of-school children live 2 miles or

more from school. In general the proportion of the out-of-school

children living long distances from school is greater than that of those

attending school. Many of the older out-of-school children living long

distances from school are most likely not in school because there are no

high-school facilities near their homes; others, as will be seen

presently, have because of the long distances and other reasons,

attended school so irregularly that retardation and lack of interest

have resulted in their discontinuing school before reaching high school.

[TABLE]

|

|

| 45 |

045 |

Relationship of school attendance to

availability.—Distance from school probably influences the number of

days per year and the total number of years children attend school as

well as enrollment. Tables 24 and 25 concern, respectively, the actual

number of days attended by the designated groups of 7,152 children in

school and the grade levels reached by 1,604 out-of-school children at

the time they left school. An examination of table 24 indicates

approximately two-thirds of the sampling reported attended school 130

days or fewer; two in seven attended 50 days or fewer. The median days

attended ranged from 90 in Wolfe County to 142 in Lumpkin County. Of the

sampling of out-of-school children reported (table 25) all but 100 were

13 years of age or older. Of the latter, approximately one-half were in

grades 3-6 when they last attended school; a few had been in grades 1-2

and the remainder had reached the seventh grade which probably was the

highest grade offered in many of these mountain schools. Both the poor

attendance and the fact that so many of the children fail to continue in

school beyond the sixth grade suggest pointedly the effects of long

distances and related influences. One recognizes the difficulties

involved in providing adequate school facilities, elementary and

secondary, to children living in remote isolated

[TABLE]

Table 24: Number and percent of non-transported

children attending school the number of days indicated during one year.

communities, especially when those resulting from sparsity of

population are aggravated by the presence of mountain conditions and an

inadequate economic basis of school support. A permanent solution

probably involves fundamental reorganization of the system |

|

| 46 |

046 |

of administration and support in addition to

initiative on the part of officials responsible. While some of the

difficulties inherent in the physical conditions indicated may be

overcome by more immediate remedies such as adequate school funds and a

more practical program of studies complete solution will doubtless await

the reorganization indicated.

[TABLE]

Table 25. - Children of school age not attending

school classified according to age groups and highest grade levels

reached when last in school. 1

|

|

| 47 |

047 |

CHAPTER III DENOMINATIONAL AND

INDEPENDENT NONPUBLIC SCHOOLS

Introductory Statement

In many southern mountain communities where there are no public

schools, or in which for many years there were none, missionary and

other philanthropic organizations have established schools. Reliable

data showing how many children and youth are attending such schools are

not available. It is, however, well known that some of the

outstanding successes in providing an education suited to the needs of

these isolated groups must be credited to private and denominational

schools. One has only to think of such well-known institutions as

Berea College, of Berea, Ky.; the John C. Campbell Folk School,