| 07 | ECONOMICS |

|

|

|

"Since there is now increasing evidence of environmental deterioration, particularly in living nature, the entire outlook and methodology of economics is being called into question. The study of economics is too narrow and too fragmentary to lead to valid insights, unless complemented and completed by a study of meta-economics." E.F. Shumacher, Small is Beautiful, p.54 |

|

|

|

|

|

When the economy came crashing down in 1929, few thought the downturn would last as long as it did. It was not until the beginning of WWII that recovery finally took hold. While it is now difficult to imagine (or not) that a war could come to our rescue, the fragile economics of the country during the Great Depression demanded intervention. One early intervention was the creation of a series of government programs that were designed to hold the country together through the economic crisis. [Sound familiar?] These collective programs were called the New Deal and included administrations such as the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA), the Public Works Act (PWA), the Works Progress Administration (WPA), The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), and the Indian Relief Act (IRA). These were but a few of the programs, but were the essential elements that resulted in the creation of the Blue Ridge Parkway. What Franklin D. Roosevelt attempted to do was to redistribute wealth throughout the nation, and he saw transportation as a key to economic recovery. He was only partially successful in his attempt to equalize the distribution of wealth, but his public works initiatives were largely very successful. Roosevelt was also an important player in the development of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, a portion of which rests in North Carolina. In 1937 Roosevelt came to the park to dedicate the new eastern National Park.

The Blue Ridge Parkway and the Great Smoky Mountains National Park were only a small part of the remediation for the inequitable or the mal-distribution of wealth, but the employment in the two parks was remediation that continues to pay large dividends for the geographic area. FERA made emergency grants to states to try to stem the tide of poverty. FERA was first instituted in the Hoover administration in 1932 and like the earlier ERA (Emergency Relief Act) , the new FERA program, established in May of 1933, was primarily charged to address unemployment. Unlike the Hoover program, the Roosevelt FERA program was designed not to provide outright cash to the unemployed, but was designed to provide jobs for cash. Many of those jobs included work on public lands, including the Parkway. Harry Hopkins was appointed by Roosevelt to head FERA and it is largely his social vision that was at work in the new Federal program. In 1935 FERA was replaced by the more familiar WPA (Works Progress Administration, later named the Works Project Administration). program, and Hopkins was again tapped to lead the program. FERA was the first Roosevelt administration assault on the mounting national economic and social crisis, but the WPA was the star program that continues to be associated with the New Deal and with the work on the Blue Ridge Parkway. Another important program for the Blue Ridge Parkway project was the earlier PWA (Public Works Administration) program, which was funded through the Department of the Interior. This program under the guidance of Harold Ikes, then the Secretary of the Interior, competed in many ways with the FERA program under Harry Hopkins' direction and the two directors were frequently at odds with one another. Ickes plan was to make recovery pay for itself with a series of public works projects. Under his leadership, the PWA also served as a stimulus program but it worked more with the private sector than the public sector by soliciting a series of contracted projects. It was an ambitious program, and before it ended in 1939, it had spent 7 billion dollars in private contracted bids in an effort to stimulate the economy. Roosevelt added to the progressive programs instituted early-on by Hopkins by legislating a Social Security Act, taxes on the wealthy, and an Emergency Relief Appropriation of 4.8 billion dollars that mostly funded the largest of the New Deal programs, the WPA. It is the WPA that is most closely associated with the construction of the Blue Ridge Parkway and it is the WPA and the earlier Agricultural Adjustment bill, that was legislated in 1933, that attempted to reconcile the rapid urbanization of America with the decline in the family farm. It is this urban and rural drama that was played out in Asheville and along many sections of the Blue Ridge Parkway.

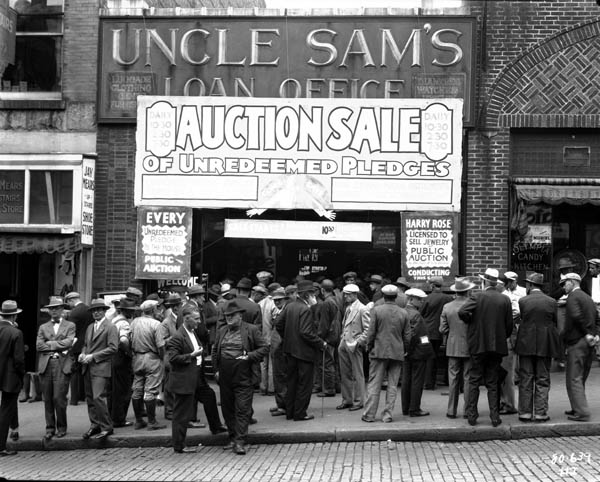

"Standing in Front of Uncle Sam's Loan Office, Asheville, NC" E.M. Ball Photograph Collection, UNCA

It has been pointed out that unlike urban families, rural families, especially in Appalachia, often fared well when it came to sustaining their basic needs, as their subsistence level was near the bottom of the measure to begin with. Yet, this observation, in the view of many is exaggerated. Most Appalachians did not believe themselves to be poor. Many mountain families have different memories of the 1930's and the picture they reflect on is of well-managed farms, abundance of food, and sufficient basic goods. Food produced on regional mountain farms was available locally by barter or through strong community relationships or communal supply, and other basic resources were available. People living in urban centers did not fare as well. The incidence of severe poverty and hardship has been well documented for urban centers during the Great Depression.

The lessons learned during the New Deal were lessons that carried on into later farming practice. The drastic measures called for in the restricted crops, raised the farm prices and provided much needed income to farm families, but the share-cropper and the farm tenant suffered major blows. Most of those non-owners were African American. As farm laborers and also as domestic service laborers, blacks and other minorities were often excluded in legislation for social insurance and wages and hours and many of them sought work in other locations. Some came to work on the Blue Ridge Parkway where they were paid equitably, in most cases. Today the Blue Ridge Parkway winds its way through twenty nine counties and contributes two billion dollars each year in revenue to North Carolina and Virginia. Two billion dollars is the amount paid out over the entire lifetime of the CWA program. The Blue Ridge Parkway today produces twice as much revenue as the entire federal program produced in one year in 1933. Where do the revenues from travel and tourism go? Generally the revenue goes back to the county and to the cities along the route of the Parkway, but a hefty share goes into the State Department of Commerce coffers. Hotel tax, restaurants, gift shops, gas stations, recreation facilities and other revenue generating facilities provide some local revenue, but in North Carolina the general revenue from travel and tourism is the largest income for the state and the Department of Commerce, one of the most powerful departments in North Carolina. Revenues from tourism is greater than manufacturing, and greater than agriculture. Given this picture, the Blue Ridge Parkway has more than paid for itself and contributes solidly to the stability of income for the entire State of North Carolina. Putting revenue back into this state-wide revenue resource makes sense, but unfortunately today, fewer proportionate dollars from Commerce go back to many of the sources of the revenue such as heritage sites, Parkway, museums, and archives. The gains to the Parkway from land donations is substantial. Other organizations, such as the Blue Ridge Parkway Foundation in cooperation with the National Parks Service, has since 1997 been " .. participating in and funding a variety of projects to enhance the experience of visitors to the Parkway." The Conservation Trust of North Carolina has also been a steady contributor to the welfare of the Parkway under its former two organizations: the Blue Ridge Rural Land Trust and High Country Conservancy, which merged to create the Conservation Trust of North Carolina. Their emphasis is on the preservation of working farms, forests, rivers and streams, mountain ridges, and wildlife habitat, and many of those abut or are associated with the Blue Ridge Parkway. |

|

|

|

|