|

|

|||

| 01 | NOT SO 'BACK OF BEYOND' : URBAN ECHOES ON THE BLUE RIDGE PARKWAY | ||

|

|

|||

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

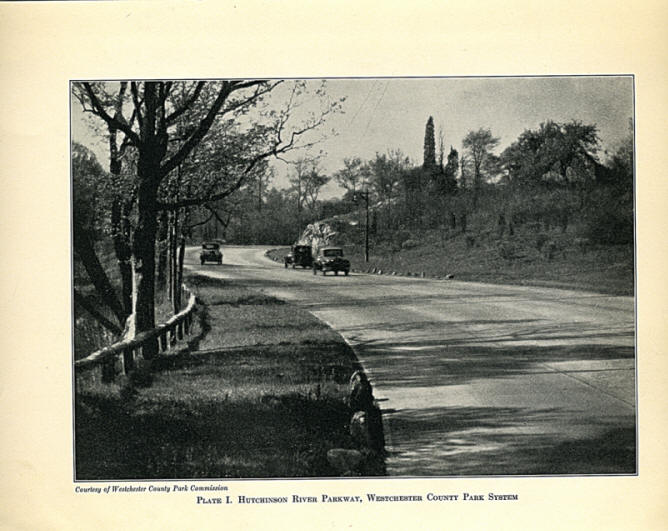

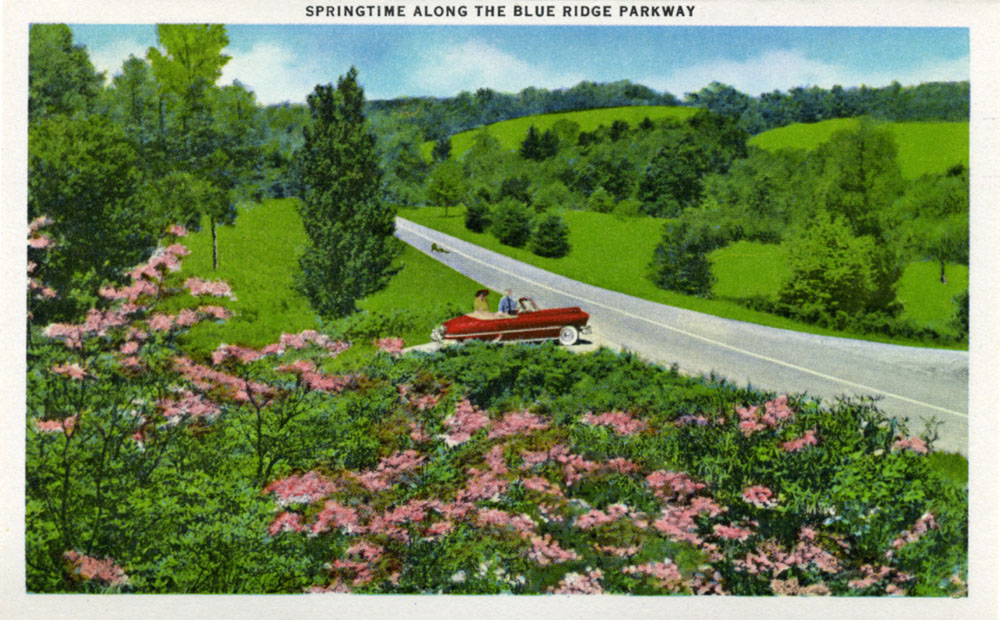

This exhibit presents a window on only a fraction of the many questions, answers, pleasures, issues, delights, and debates surrounding the construction and use of the Blue Ridge Parkway. It offers to those who have journeyed along its 469.02 miles (or so), an opportunity to reflect on this publicly held complex landscape. And, for those who have never been on the Blue Ridge Parkway, it is hoped that this exhibit will encourage exploration of some part of this scenic and wondrous roadway. The exhibit explores the Blue Ridge Parkway through the filter of its urban influences. The "urbaness" of the Parkway is found throughout the many socioeconomic and aesthetic elements of its design, construction, and use. The very nature of the Parkway does not easily call to mind an urban experience, but the "urbaness" can be found if one looks and listens to the echoes. The urban echoes are in between the many mileposts of the road, in its aesthetics, its politics, its economics, its many individual contributors (landscape architects, engineers, and workers), its issues of diversity, its environmental impact, and its current use. The urban echoes on the Blue Ridge Parkway can only be heard if one listens carefully and cares to see this long, thin, black road in a park through a different lens. The anonymous author of the "The Proposed Speed-road in Central Park," argues, that the new road in Central Park would "enable a few opulent citizens" to enjoy their chosen pastime for a few weeks in the Spring and Autumn, "during which time the horsemen would find nothing but the experience of driving itself, the 'exceeding great reward' along the new road." The anonymous writer asks the reader to visualize the proposed new pleasure road through an aesthetic lens. He likens the proposed new road to the desecration of a landscape painting "whose image is partially cut away." The deeply held visual beliefs of the anonymous writer come from his personal response to changes in an urban landscape that he believes belongs to him. We all have deeply held beliefs about our landscapes and their uses. Whether the landscape is our urban space or our rural landscape, these are spaces we have been conditioned to view with an appraising eye. We measure the landscape against a subliminal standard of visual organization that is conditioned by our values, our childhood experiences, and our physical visual acuity. Viewing is always tied to feelings, that we often describe as 'our aesthetic', conscious or subliminal. Whether it is the aesthetics, the politics, the planners and engineers, the travel and tourism economics, the issues of diversity, or the environmental aspects of the Parkway, the viewed aggregate in this exhibit is from the urban vantage point and its socioeconomic consciousness. "Urbaness" is as much a part of the Parkway, as are the Mile Posts scattered along the 469.02 miles, (or so), of this famous road. The urban echoes in the Parkway create a tension within the pastoral landscape that can be both felt and seen along the route. Leo Marx described these tensions in his provocative book, The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the pastoral ideal in America, (1964). He suggests that the the rise of the machine and industry in the early 1800's was the point at which our pastoral society underwent an important cultural split. The intrusions into the landscape are, in his view, "tokens of industrial power" introduced into the serene environment and into the idyllic setting of nature's garden. The intrusion of the discordant machines; artifacts of industrialization. Marx tells us that these 'intrusions' breed feelings of foreboding, anxiety, distress and dislocation. Early elements of this discontent is seen in the anonymous author, above, who complained about the re-design of 'his' roadway in Central Park, and he saw an intrusion on the scenic beauty and authenticity of 'his' familiar landscape.' The evocations of this writer are not uncommon to his time, as there were strong emotions associated with industrialization in the late nineteenth century. Many novels and works of art in the late nineteenth century and the early years of the twentieth century, detail the cultural shift at work in the confrontation of naturist and conflicted industrialist. In his Machine in the Garden, Marx describes the cultural shift as an "interrupted idyll" brought on by industrial capitalism with all its economic baggage. He suggests that when technology enters into the pastoral and natural environments it represents a major cultural shift and sets up an intellectual divide. In this country a divide was created between those who accepted material progress as their primary goal, and those for whom whom material possession was not fulfilling. We have yet to find ways to cross this divide effectively and as late as the 1980's one of the most dramatic industrial artifacts was introduced as a cap-stone project along the Parkway at Grandfather Mountain.

Called the Linn Cove Viaduct, this massive engineering project wraps around the face of rugged Grandfather Mountain and shouts "interrupted idyll." One of the most dramatic representations of the tensions of the "machine in the garden", it continues to call forth the same strong reactions found in the "Proposed Speed-road ...." article. Unlike the the rest of the roadway along the Parkway which either hugs the contours of the landscape and in many cases penetrates it in a series of tunnels, this cantilevered and extra-terrestrial testimony to man's achievement, is often the visual icon depicted in the later literature of the Parkway. Like a Disney ride, this industrial artifact speaks to our fascination with technological challenge as well as our need to escape to another realm of adventure. The Linn Cove Viaduct is both a token of industrial power and an exquisite and sinuous brush stroke across a muted canvas. It is both authentic and inauthentic experience and the tension of pride, dislocation, awe, and foreboding suspends us in time and place. Getting away to nature and out of the industrial city in order to relax and refresh is not only promoted in early Parkway literature, it was planned for in the design of the Parkway. The early idea that the escapee could get in a car and have a continuous experience with parks and wilderness was under discussion before any construction began. The idea of an open country, where the urban dweller could find a "get-away," an ideal vacation and be refreshed by escape to an unexplored region, is part of the intent of the designers. Regionalism, also a unifying factor for the Parkway, is a geographic tool for drawing boundaries around an experience. The planners called for the Parkway to tie together the two magnificent parks at either end of the project: The Shenandoah Park and the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The two parks were to be enhanced by the addition of the connecting Parkway which enlarged the boundary of experience and provided a means to increase the economic gains of all three parks. It is little wonder that Disney set its sights on a new theme park in the Shenandoah Valley. Postcard folio - Description of Early Parkway

The Parkway's thin black thread of a road, some 469.02 miles, (or so), in length, reaches across 216.95 miles of southwest Virginia and 253.07 miles of north-western North Carolina.

It is in many ways an artifact of several earlier utopian visions and designs. The men whose vision shaped the Parkway had already seen the success of Yosemite and Yellowstone, and the eastern Shenandoah National Park. They gave to the Parkway their escapist dreams and the subjective sum of their experiences. Harold Ickes, the director of the Department of the Interior, Harry Hopkins, the New Deal genius, Stanley Abbott, the young visionary who was charged with the design of the Parkway and the multiple engineers on the project were either urban escapists, urban reconstructionists, or open space preservationists and most had their roots in urban soil. The naturists write of protecting and promoting the Parkway's beauty, its verdure, and the virtual healing properties of the drive along the road. These protectionist views were at work in the Central Park debate, as well as the Parkway discussions. Both the anonymous author protesting the Central Park changes and the Parkway protectionists, held the idea that parks were not to be used as theaters for spectacle. This is a value only partially held in today's see and be-seen park environments. Early Reconstructionist Influences The years, 1930-1942, while a brief span of time, were very important to the cultural life of the country. It was a time permeated by urban reconstructionist ideals but dominated by individuals who were conflicted in the implementation of those ideals. A reconstructionist mind-set can best be understood by briefly exploring the live of two individuals who set in motion the utopian reconstruction of the lands through which the Blue Ridge Parkway threaded. Thomas Jefferson and Tench Coxe were two well-known reconstructionist utopians whose visions helped to give shape to the ideas and the geography across which the Blue Ridge Parkway runs. It is the prescience, the forward looking ideas, the anticipatory reconstructionist utopian visions, of these two individuals, that resonate so remarkably with the geography of the Parkway. At the heart of their differences are two views: industrialization and preservation/conservation. Jefferson, the essential southern Republican planter, was more frequently pulled toward his origins and the origins of the country, the virgin wilderness, and its Edenic charm. Coxe was the quintessential urban Federalist merchant, an industrialist, who was both attracted to industrialization and repelled by it but for most of his life he had his sights on the 'Shining City on the Hill.', the New Jerusalem. Both men imagined the coming industrialization in ways that were later exposed and dramatized in the cultural dissonance of landscape architecture and those who planned this ribbon of asphalt, we call the Blue Ridge Parkway. |

|||

|

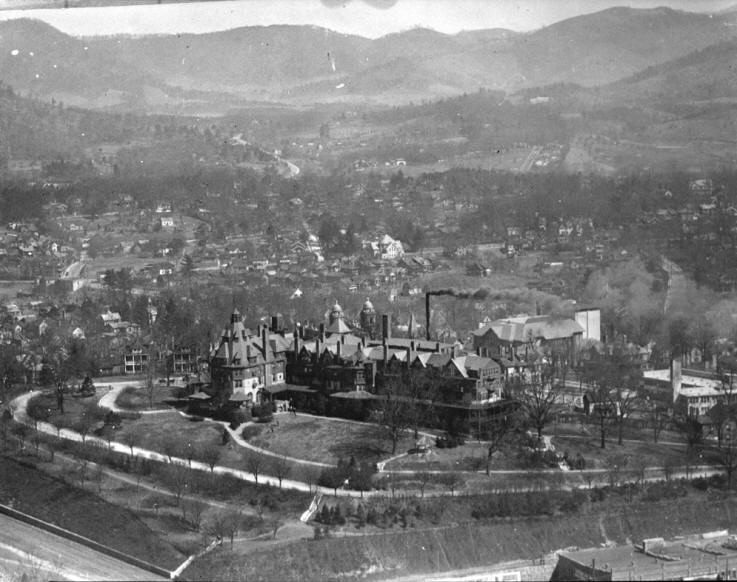

Battery Park Hotel It was Tench Coxe's descendent, Col. Frank Coxe who found the true wealth of the western North Carolina region, ---its tourist appeal. Through Colonel Coxe's efforts the Western Railroad came across the Blue Ridge at the Swannanoa Gap and into Asheville in 1880. In 1886 the Spartanburg to Asheville Railroad opened. In that same year Col. Coxe opened the doors to his magnificent Battery Park Hotel and around this hotel, the 'Shining City on the Hill.', or, 'in the Hills', began to take shape. Coxe's hotel set the standard for southern hotels and resorts for years to come. Following the construction of the Battery Park Hotel, Asheville and western North Carolina became a center for tourism and it was Coxe, more than any other individual, who opened the doors to travel and tourism in the western part of the state and established the economic base for the industry. |

|||

|

|

Coxe was also a railroad man. Through his Pennsylvania coal interests he became a man of substantial wealth. In 1881 he moved to Charlotte where he became the vice-president of the Western North Carolina railroad, the first railroad to traverse the mountains of western North Carolina. The railroad came to western North Carolina largely through the funding of Col. Frank Coxe and the tourists came largely because of the railroad. Shortly after 1881, Col. Coxe moved to Asheville. His machines, the locomotives, crossed the Blue Ridge and entered Eden. He turned Eden into a commodity and sold it to an enthusiastic audience. The selling of Eden was not difficult for Coxe and it was not difficult for those who planned the Blue Ridge Parkway. |

||

|

The painting of an 'Edenic' western North Carolina, formed the central argument for the North Carolina Parkway advocates. There were no arguments in this group with Coxe's vision and with the scenic appeal of the region for nearby urban centers, nor for its business economics. The arguments were to come later. As the Parkway idea evolved, the arguments surrounding the various visions and ideologies grew. The regionalist and the metropolitanist, the naturist aesthete or the dictatorial aesthete, the liberal and the conservative, the politician and the environmentalist, the urbanist and the rural dweller, white and black and brown, and female and male, all struggled to find a role in and along the Parkway. Sometimes the visions of these people were spiritual, sometimes economic, often political, sometimes aesthetic, and occasionally the vision was densely theoretical, but all visions shared one thing in common ---- their sincerity. |

|||

|

The planning of the Blue Ridge Parkway still begs the question. Were the planners of the Blue Ridge Parkway reconstructing their landscape into a carefully built and ordered New Jerusalem, or were they designing for their escape to the Edenic land of personal liberty and innocence? Were the sources of the Blue Ridge Parkway found in reconstructionist ideals? Or, are they rooted in preservationist ideologies? Are the "machines" in the garden, attempts to move the country forward? Or, were they simply visions and desires, extracted from individual cultural heritage? This exhibit does not propose to answer these difficult questions of intent or to intentionally foreground one view over another, but it does intend to keep the debates active and the ideas flowing as we enter into the seventy-fifth year of this elongated road within a park. By looking backward and forward through text and image, it is hoped that some new discoveries will be made and that the viewers will be moved to fix their gaze and their minds on the many potential visual wonders and the ideas offered by this collective community park, garden, parkway, utopia, roadway, and heritage journey, and to reflect on what it might mean if this extraordinary parkway did not exist. |

|||

|

Selling the Blue Ridge Parkway - Scenes

"Scenes Along Blue Ridge Parkway," Asheville Postcard Co., folio, 1950's |

|||

|

The debates associated with the Parkway have from the beginning begged the question of whose "beauty" and whose aesthetic is at work in the creation, maintenance, and use of the Parkway? Is the aesthetic of the Parkway a construction or a reconstruction? Is the ideal aesthetic best found in urban origins? Is the "authenticity" and experience of the Blue Ridge Parkway fabricated? Is "beauty" and the "Back of Beyond" a concept to be framed and sold? Exploited? Is the Parkway a conception of an urban "opulent society" pleasure park, or a WPA project built on the backs of the poor? Or, conversely, did the Parkway open to the American public employment and opportunities that did not exist? Is it only a scenic area of healthful fresh air, a rejuvenating and leisurely ramble through fabricated authenticity? An escape? Is it just 469.02, (or so) miles of roadway where beauty, rest and relaxation are made accessible? Did the parkway acknowledge the growing mobility and desires of all segments of the population by providing an accessible pleasure park within driving distance of the largest population base in the United States? To whom did it deny access? Who is the Blue Ridge Parkway for? Who will it serve in the future? There are no easy answers to these questions. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||