| 06 | PEOPLE | |

|

|

||

|

HORACE MARDEN ALBRIGHT (1890-1987) |

||

|

Horace Albright, a protégée of the first director of the National Park Service, Stephen Mather was there at the beginning of the planning process for the Blue Ridge Parkway. It is his dedication to the idea of a National Park Service bill that saw the bill through to enactment in 1916. This early organizational work for the National Park Service and his careful wording of the so-called "creed" for the National Park Service set the tone for the department from those earliest days to the present. A graduate of the University of California, Berkeley in 1912, Albright did not have an urbanist origin ... at least some would not claim Bishop, California in the early decades of the twentieth century as a major urban center. Bishop, on the "other side of the Sierra Madre mountains, is a farming community but at the doorway to some of the most rugged and spectacular scenery of the Sierras. Albright throughout his life showed a clear preference for the western landscape, and as a former Superintendent of Yellowstone National Park and Assistant Director (1919-1929), he knew the parkland of some of the countries earliest and most beautiful parks. Upon graduation from Berkeley, Albright went to Washington where he began his life-long career as a public servant. He was first a clerk and then assistant to Stephen Mather Director of he National Park Service. His later appointment to Yellowstone and his return to Washington in 1929 to serve as Director of the Department gave him one of the broadest perspectives of any Director of the agency. While many of the organizational structures still seen in the National Parks Service go back to Albright, it is Mather who sits behind it all. He was a forceful influence on Albright and they shared many of the romantic notions of "regionalism" that helped to form the basis for planning of the Blue Ridge Parkway. One of Albright's major contributions to the National Parks Service was the introduction of historic preservation into the National Parks Service and in 1931 all National Monuments and Military Parks were transferred to his department. Albright is remembered by his staff as a man of integrity, great honesty, humor, and a rabid devotion to the National Park Service and its mission. By 1933 he had retired from his government office and became president of the United State Potash Company (1933- 1956). He returned to California where he died on March 28, 1987, at the age of 97. |

||

| BIBLIOGRAPHY: For more information on Horace Marden Albright see : National Park Service: The First 75 Years

|

||

|

|

||

|

STANLEY ABBOTT (1908-1975) |

||

|

On June 30 of 1936 Congress formally announced the establishment of the Blue Ridge Parkway with the act [Public Law 848]. The Parkway was placed under the jurisdiction of the National Parks Service and Stanley Abbott was officially named the Resident Landscape Architect and the Acting Superintendent in March of the following year, 1937. He was only 25 years old. He remained as the lead designer of the Parkway and its Superintendent until the outbreak of WWII when he was called into service for the war effort. Abbott's youth was not a deterrent to his appointment by two of the founders of parkway design, Jay Downer and Gilmore D. Clarke. When he was appointed to oversee the creation of the Blue Ridge Parkway, Abbott was already well-known in the small circle of landscape architect professionals. He was one of the founding members of the Society of Landscape Architects, the close circle of professionals. Abbott, often described as a 'regionalist' found in Harold Ickes and others associated with the parkway design, an opportunity to extend his vision of an environmentally sensitive design plan that would preserve the cultural history found along the parkway route. He was, by some accounts, an enlightened land manager and with R. Getty Browning, the North Carolina primary engineer, produced a parkway that remains one of the most significant examples of landscape architecture in the country. Abbott was born in Yonkers, New York and his urbanist origins and close proximity to the largest city in the country left a lasting impression on him. His professional training was through Cornell University where he studied landscape architecture and immediately was employed to work with the Westchester County Parks Commission in New York. He also was engaged in the planning phase of the Finger Lakes State Parks recreation area and it is in these two jobs that his strength as an administrator shown. His interest and expertise in park design and in land use planning can be seen in the early planning for the Blue Ridge Parkway. His sensitivity to the park as an extension of the urban environment is clearly seen in many of his planning documents, particularly his interest in "landscape improvement." He gave landscape work his highest priority when prioritizing the maintenance projects of the New Deal CCC camp workers. Later in his career Abbott worked for the NPS to plan the Mississippi River Parkway and in 1953 he returned to the East to work on the Colonial National Historical Park in Virginia. As head of his own landscape architectural design firm he completed many significant projects in Virginia, including Virginia Military Institute, Virginia Polytyechnic Institute, the Governor's Mansion, and the four Virginia colleges of Radford, Roanoke, Mary Baldwin, and Hollins. |

||

| BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Stanley W. Abbott, "Historic Preservation: Perpetuation of scenes where history becomes real," Landscape Architecture 40(4), July, 1950: Blue Ridge Parkway. HAER No. NC-42, p. 75-76 Cultural Landscape Foundation http://tclf.org/content/stanley-abbott |

||

|

|

||

|

FRED AND CATHERINE BAUER |

||

|

Fred Bauer, the Vice Chief of the Eastern Band of the Cherokee Tribal Council during the years of construction of the far western Blue Ridge Parkway was not born in the Qualla Boundary, but came there to live following an early life and education on the East Coast. Catherine and her husband, Fred Bauer were referred to as 'White' Cherokee and they were often determined to not follow the Cherokee community in many of their positions. However, Fred's family ties with Jarrett Blythe, who was a half-brother, gave both Fred and Catherine a central place in the small Cherokee community. Both were persuasive speakers and their conservative ideology resonated with many in the community. The Bauers were particularly outspoken with regard to the "Communist menace" and it was most likely Catherine's outspoken opposition to a standard school text book that contained elements of what she believed to be communist overtones, that resulted in her conflict with Foght. The source of her subordination is unclear, but while substituting at the Soco school she discovered in a history text what she believed to be 'Communist' sentiments and she called this to the attention of school authorities and requested the removal of the text from the curriculum. The accusations began to fly and Catherine was asked to resign her post. Part of her disgruntled stance was no doubt the result of the recent controversies surrounding the Indian New Deal which, in Catherine's view, left much to be desired and smacked of socialism, particularly as it applied to education. Foght saw the Indian New Deal differently than Catherine and was supportive of John Collier, the Commissioner and his reform actions. The acrimony in this initial dispute escalated into one of the most interesting theoretical and political debates within the Cherokee tribe and within the context of the New Deal programs. Catherine Bauer was a graduate of Cornell University and came to western North Carolina to teach as a substitute teacher at the BIA school in the Qualla Boundary in 1934. She received excellent reviews for her work and by 1935 she was recommended by her supervisor for a permanent position at the Soco Day School, located in the Soco valley area of the Qualla Boundary. Just shortly after that permanent appointment she had a confrontation with the supervisor who had recommended her work and the confrontation was so severe that Harold Foght, the Superintendent of the North Carolina Cherokee, Department of the Interior and Catherine's supervisor, lodged a formal complaint of insubordination against her. |

||

| BIBLIOGRAPHY: Finger, John R.. Cherokee Americans : The Eastern Band of Cherokees in the Twentieth Century.. Lincoln : University of Nebraska Press, c1991 Eaton, Rachel Caroline. John Ross and the Cherokee Indians, Menasha, 1914. |

||

|

|

||

|

JARRETT BLYTHE |

||

|

Chief of the Tribal Council of the Eastern Band of the Cherokee who opposed Fred and Catherine Bauer's proposal for the Blue Ridge Parkway's route through the Qualla Boundary and favored a route that is essentially the one in existence today. Described by some as the most popular and the smartest Chief to ever head the Eastern Band of the Cherokee, Blythe was very adept at playing both sides of an argument. He was Chief from 1931 until 1937, just short of the end of his term in office. The North Carolina Eastern Band of the Cherokee, unlike their Oklahoma tribal brother, did not relinquish their tribal organization and government and they continue to retain all tribal government today. The composition of that government requires that two members be elected from each of the five townships in the Qualla Boundary. The grand council meets in October of each year and is generally called together by the principal chief and he makes a report on the welfare of the tribe. |

||

|

BIBLIOGRAPHY |

||

|

|

||

|

R. GETTY BROWNING (d. 1966) |

||

|

R. Getty Browning was the Federal Parkway Engineer and the Senior Locating and Claim Engineer for the Blue Ridge Parkway. It was his work that guided the initial exploration and design of the parkway. He trekked the ridgelines of the Blue Ridge to find the optimum route and it is Browning who made the recommendations to Abbott and to the engineers regarding the geography and the view-sheds and ultimately was called to Washington where he presented a persuasive argument to Harold Ickes for what became the route of the Blue Ridge Parkway. It was Browning's maps that were given to the Secretary of the Interior in 1934 as preparation for the Parkway planning and which acted as the catalyst for the acceptance of the Blue Ridge Parkway plan. Later, in one of the many trips to western North Carolina made by Ickes and by Arno Cammerer, his assistant, it was Browning who was called on to escort the dignitaries on planned trips to the Blue Ridge Parkway construction sites and to the surrounding mountains. Browning knew his western North Carolina geography, as he had spent countless hours walking the route that would later become the parkway. Fred Weede describes a mapping trip that Browning led for those who were promoting the new parkway. A native of Maryland, Getty started his career as a surveyor. He worked in West Virginia as a bridge surveyor and for the railroad and then back to Maryland for the Maryland Roads Commission which was centered in Baltimore.. He came to North Carolina in 1920 to work for the newly formed Highway Commission in that state and stayed for the remainder of his career. He became the chief location and claim engineer for the North Carolina Commission and was responsible for many highways within the state, including the Blue Ridge Parkway. A resident of Durham, North Carolina, Browning moved to Raleigh in 1925 when he was promoted to the position of director of the Location and Right of Way department fro the Highway Commission. He was a significant contributor to the war effort and was charged to assist the Navy in development of a large munitions plant. He also played a key role in the production of tankers used in the war effort. As one travels on the Blue Ridge Parkway and arrives at Milepost 451.2, a plaque that honors Browning and his work on the Blue Ridge will be found. If the traveler looks up at the peaks near the city of Waynesville, North Carolina, they will see a high peak of some 6,000 feet. This is Browning Knob, named for the indefatigable mountain lover, R. Getty Browning. |

||

| BIBLIOGRAPHY: | ||

|

|

||

|

JOHN COLLIER

(May 4, 1884 - May 8, 1968) |

||

|

Roosevelt recognized Collier's valuable contributions to Indian welfare and appointed him to the the office of Commissioner of Indian Affairs in 1933 and in this position, Collier proposed the Indian New Deal in 1934. The Indian New Deal, part of FDR's New Deal programs was supported by the passage of the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, which by most accounts was one of the most sweeping reforms of Federal Indian policy and which reversed the assimilation policies of all previous administrations. Also referred to as the Wheeler Howard Act, the legislation returned Indian Land to communal property and encouraged self-determination of the Indian, reversing the 1887 Indian General Allotment Act that promoted assimilation. It was this Act that spawned the fierce debate between Fred and Catherine Bauer and some segments of the Eastern Band of the Cherokee regarding the route of the Blue Ridge Parkway through Indian land. |

||

| BIBLIOGAPHY: Finger, John R. Cherokee Americans : the eastern band of Cherokees in the twentieth century. Lincoln : University of Nebraska Press, c1991 |

||

|

|

||

|

HARRY HOPKINS

(August

17, 1890 – January 29, 1946) A valued advisor to FDR, Hopkins was a native of Sioux City, Iowa where he attended the small but prestigious Grinnell College, a liberal arts institution well known for its progressive education. Upon graduation in 1912, Hopkins was employed by Christodora House*, a settlement house on the Lower East Side of New York City on Tompkins Square, where he quickly became a valued employee and met John A Kingsbury who headed the AICP (Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor in New York). |

||

|

|

|

| BIBLIOGRAPHY: | ||

| Adams, Henry Hitch.

Harry Hopkins: A Biography (1977)

Bremer, William W. "Along the American Way: The New Deal's Work Relief Programs for the Unemployed." The Journal of American History 62 (1975): 636-652. Hopkins, June. Harry Hopkins: Sudden Hero, Brash Reformer. (The Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt Institute Series on Diplomatic and Economic History.) New York: St. Martin's. (1999).Biography by HH's granddaughter. Hopkins, Harry L. "Boondoggling: It Is a Social Asset." The Christian Science Monitor (August 19, 1936): 4, 14. Hopkins, June. "The Road Not Taken: Harry Hopkins and New Deal Work Relief" Presidential Studies Quarterly Vol. 29, 1999 Howard; Donald S. The WPA and Federal Relief Policy (1943) online edition Kurzman, Paul A. "Harry Hopkins and the New Deal", R. E. Burdick Publishers (1974) McJimsey George T. Harry Hopkins: Ally of the Poor and Defender of Democracy (1987), biography. Meriam; Lewis. Relief and Social Security (1946). Highly detailed analysis and statistical summary of all New Deal relief programs; 900 pages; Sherwood, Robert E. Roosevelt and Hopkins (1948),a memoir by a senior FDR aide and a Pulitzer Prize winner . ISBN 978-1-929631-49-0 online edition Singleton, Jeff. The American Dole: Unemployment Relief and the Welfare State in the Great Depression (2000) online edition Smith, Jason Scott. Building New Deal Liberalism: The Political Economy of Public Works, 1933-1956 (2005) Smith, Jean Edward. FDR, Random House (2007) "Harry Lloyd Hopkins". Dictionary of American Biography, Supplement 4: 1946-1950. American Council of Learned Societies, 1974. |

||

|

|

||

|

HAROLD ICKES (March 15, 1874 – February 3, 1952)

|

||

|

It was Ickes who ordered the desegregation of our National Parks in the 1930's, including the Blue Ridge Parkway. And, it was Ickes who made the final approval on the route the parkway would take out of Virginia. He decided on the North Carolina route. If Ickes had one very strong suite (he actually had many), it was his staying power. He was with the Franklin D. Roosevelt cabinet for the length of Roosevelt's terms in office. He served the longest term ever as head of the Department of the Interior. Roosevelt has a number of men who were considered the "Brain Trust" of the President. Ickes was was more like a "trusted brain". He could always be counted on to hold fast to his ideas and to always chart the high-road in any debate, particularly those that involved humanitarian issues. Ickes contributions to the shape of our country and to our National Parks cannot be exaggerated. Something of a thorny personality, Ickes did not like Abbott and the two locked horns on many occasions. He also had several contentious rounds with Harry Hopkins and is known to have "seen the world differently" from Hopkins on many issues. Roosevelt, however pulled from all those around him the best of their ideas and Ickes had more than a few. |

|

|

His background like so many of those whose ideas shaped the Blue Ridge Parkway, was urban. He was born in Altoona, Pennsylvania and moved to Chicago when he was 16. He attended the University of Chicago and completed a B.A. in 1897 and later in 1907 received his law degree from the same institution For a brief time he worked as a journalist with The Chicago Record and later for the Chicago Tribune. His experience as a reporter gave him a keen knowledge of people and of social action which led him into the world of reform politics. The remarkable social activism of Ickes is seen in his role as president of the Chicago NAACP (1923) and his life-long commitment to the rights of minorities and people of color. He spoke out against the internment of Japanese during WWII and acted as a representative for the Roosevelt administration during the founding conference of the United Nations in San Francisco. In foreign affairs he favored independence for the world's colonized countries, and promoted self-rule of those colonies. He was a Republican by political persuasion and came to the Roosevelt cabinet on the recommendation of his long-time friend Senator Hiram Johnson, whom he knew from Chicago. Roosevelt was interested in placing on his cabinet a progressive Republican who would bring in those of similar persuasion in the Republican party and Hiram Johnson, who was Roosevelt's first choice recommended his friend, Ickes. While he served in the President's Cabinet as the Secretary of the Interior, he also served simultaneously as the director of Roosevelt's PWA (Public Works Administration) the New Deal program that first supported the development of the Blue Ridge Parkway. It was Ickes who ordered the desegregation of our National Parks in the 1930's, including the Blue Ridge Parkway. His efforts on the part of African Americans was only partially successful against Jim Crow but opened the way for the eventual equitable access to our national park system by African Americans. And, it was Ickes who made the final approval on the route the parkway would take out of Virginia. He decided on the North Carolina route. |

||

|

|

||

|

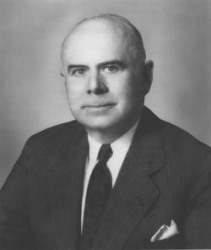

THOMAS H. MacDONALD "THE CHIEF" (July 23, 1881 – April 7, 1957)

Director of the Bureau of Public Roads |

||

|

Generally given the credit for first proposing the Parkway as an extension of Virginia's Skyline Drive. MacDonald was the Director of the Bureau of Public Roads and with the backing of John G. Pollard, MacDonald first promoted the idea through Senator Harry F. Byrd of Virginia to President Roosevelt and then Secretary of the Interior, Harold L. Ickes. In the initial meeting with Senator Byrd to discuss the proposal, MacDonald declined to take credit for the idea and said to the committee that the idea was the outgrowth of conversations with other intreested parties, including Radcliffe and Straus of the Public Works Administration. MacDonald indicated that the project addressed the "Necessity to provide, or rather to make available, certain facilities which we have, and to which we have not in the past given as much weight as I think we are justified in giving. |

||

|

|

This gentle persuasion was all that was needed with the receptive committee and by the end of the meeting the motion to proceed was accepted and a committee was planned and members from the group chosen to represent the interests of the three state stakeholders. All agreed that the plan, whatever its form would be a Federal plan with state cooperation and that the road would begin at the Shenandoah and would possibly end at at Spotswood, NC. [TN ???]. This plan was dramatically changed when the final route was approved by Ickes. MacDonald was born in Leadville, Colorado on July 23, 1881 and moved shortly with his family to Montezuma, Iowa where his father dealt in grain and lumber. His educational background included an undergraduate degree from the Iowa State Teachers College where he studied with Anson Marston and received a B.A. degree in civil engineering in 1904. After graduation he was retained by the College and three years later in 1913 he was hired by the state of Iowa to be the chief engineer, or head of their three-person highway commission. In his Iowa position, Macdonald worked closely with Logan Page who was serving as the chief of the federal Bureau of Public Roads and who was an officer in the American Association of State Highway Officials (AASHO). It was this association that brought him to Washington in 1918 following Page's death. |

|

|

While associated with the AASHO MacDonald helped to write and legislate the Federal Aid Road Act of 1916. He later served as the President of the organization. In Washington MacDonald served as the Chief of the Bureau of Public Roads (BPR) for nearly 34 years. Influenced by the work and ideas of Logan Page, his predecessor, Thomas Macdonald was for all intensive purposes a Progressive but did not promote himself or the ideology, preferring to keep a low profile and a rigorous work ethic which he used to push through numerous changes in the Bureau. One of the most lasting contributions to road-work made by MacDonald was his concept of limiting funds for construction to a federal-aid system, it was this financial restructure that made the federal highway a success under his administration. Our current interstate system owes much to MacDonald's ideas and his management but ironically, he was not an automobilist. In fact in 1947 he noted that the "preferential use of private automobiles" in our cities was creating serious issues for quality of life in the city and that the trend indicated a movement toward mass transit. He was so right when he warned that if individuals could not be separated from their automobiles "the traffic problems of the larger cities may become well nigh insoluble." By all accounts he was emotionally austere but commanded enormous respect from all who worked with him. When he was eulogized a friend said of him that he was "a statesman who built an enduring monument to himself not so much in roads and bridges as in the lives of people." MacDonald retired from the Bureau of Public Roads in 1953 and died shortly after that on April, 1957 [1958 ?]. |

||

| BIBLIOGRAPHY: Biographical Dictionary of Iowa: MacDonald, Thomas Harris Pete Davies, American Road Stephen B. Goddard, Getting There: The Epic Struggle Between Road and Rail in the American Century Tom Lewis, Divided Highways: Building the Interstate Highways, Transforming American Life US Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration

http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/infrastructure/rw96d.cfm |

||

|

|

||

|

BENTON MacKAYE (March 6, 1879 – Dec.

11, 1975) |

||

|

(March 6, 1879 – Dec. 11, 1975) "The effect of an unbalanced industrial life, ... is the cause of an unbalanced recreational life." Benton MacKaye, founder of the Appalachian Trail, saw recreation and mobility very differently than did those who developed the Blue Ridge Parkway. Both the Parkway planners and Mackaye, however, focused their visions on the ridgelines of eastern mountains. It was the competition for nature's high places that finally brought McKaye directly in conflict with those who developed the Parkway. MacKaye is one of the best counter-points to study when evaluating the history of the Parkway. While he supported the idea of land preservation for recreation and conservation purposes, held by Abbott, Ickes and Hopkins, he held a more balanced view of human needs in the planning cycle. The formation of MacKaye's wilderness ideas came near the end of 1921 in an article that didn't mention the word "wilderness", once. The article published in the October issue of the Journal of the American Institute of Architects was a treatise on recreation camps which he believed would provide a healthy form of recreation for the public just recovering from World War I. In his recreation camps he imagined that the act of camping would bring the leisure seeker to understand "the problem of living." Horace Kephart (1862-1931) produced his popular manual, The Book of Camping and Woodcraft; A Guidebook for Those Who Travel in the Wilderness, in 1915, (New York, Outing Publishing Company) some five years before MacKaye's article appeared. The two held many views in common though it is unlikely that MacKaye would have tolerated Kephart's life-style. Benton MacKaye's efforts to save America's wilderness and to preserve regions threatened by "metropolitianism" is legend. One of two founding members of the Wilderness Society, he worked with the Federal government to promote wise land use and worked against the Federal government when he believed they had over-stepped their bounds and were responsible for the destruction of wilderness areas. It was his belief that the construction of the Blue Ridge Parkway over-stepped the boundaries of responsible land management and promoted "mass recreation" instead of responsible stewardship and was always uneasy with travel and tourism as an extension of commerce. For a brief time MacKaye worked with John Collier and his New Deal Indian Service and as a regional planner with the Tennessee Valley Authority, but was soon disenchanted by the efforts of the New Deal which he saw as promoting economic reforms that were ineffective and which failed to integrate the short-term work programs with the idea of long-term economic recovery. He was adamantly opposed to any development of skyline drives which he believed created too much "automobility" in the country and destroyed the valuable and aesthetically pleasing ridgelines of the mountains. A strong commnuitarian, MacKaye believed in the local and in the community provision of support and services. Most likely it was his rich family life and the many experiences he engaged throughout his life that gave Benton MacKaye the drive to succeed that he exhibited most of his life. He was born in Stamford, Connecticut on March 6, 1879 to parents who were actors and dramatists. James Steele MacKaye and his wife Mary were well known in the early years of the nineteenth century. They had a large family of six children. Benton was the youngest of the children. The family had difficulty managing their finances and moved repeatedly living for a time in Vermont, Massachusetts, New York and Connecticut and finally, New York. The family maintained a cottage in Shirley Center, Massachusetts which was a lovely, rural setting that Benton relished for its open countryside. All the children were talented and progressive in ideology. Benton's older brother Percy MacKaye, a playwright, discovered Appalachia early in his career and spent time at Pine Mountain Settlement School where he studied the mountain dialect and wrote several plays based on his encounters with the settlement school community and his experiences of living in the eastern Kentucky mountains. When Benton was fourteen his father Steele MacKaye died. His older brother William had died just after the move to Shirley Center and the two deaths were very hard for the young Benton. He did not thrive in the standard school setting and found many ways to seek his own instruction. As an autodidactic learner Benton was a voracious and rapid learner. Lewis Mumford a life-long friend of MacKayes said of his friend's learning style, "This direct, first-hand education through the senses and feelings, with its deliberate observation of nature in every guise - including the human animal -- has nourished MacKaye all his life." [Ness, "The Path Taken," Preservation Magazine, July/August 2003] He did, however, finish both a B.A in geology (1900) and an M.A. (1905) in forestry at Harvard University's School of Forestry and was invited to teach at Harvard upon graduating. He was the first registrant in the new School of Forestry at Harvard where he had gone at the urging of his two brothers, Percy, who had gone to Harvard to study drama, and James, who studied engineering and philosophy at the school. MacKaye was a large personality and his influence was felt in all the positions he held throughout his life. He worked for many government agencies that had a direct influence on the Blue Ridge Parkway, including the U.S. Forest Service, the Tennessee Valley Authority, and the U.S. Department of Labor. He was a key contributor to the Energy Survey of North America and authored two books and numerous articles on a wide range of topics. Benton MacKaye, founder of the Appalachian Trail, saw recreation and mobility very differently than did those who developed the Blue Ridge Parkway. While MacKaye frequently spoke out against our automobile society, his ideas were at work with many who were charged with the design and execution of the Parkway. One of two founding members of the Wilderness Society, he worked with the Federal government to promote wise land use and worked against the Federal government when he believed they had over-stepped their bounds and were responsible for the destruction of wilderness areas. It was his belief that the construction of the Blue Ridge Parkway over-stepped the boundaries of responsible land management and promoted "mass recreation" instead of responsible stewardship and he was always uneasy with travel and tourism as an extension of commerce. In some ways his views were forward looking and in other ways he was more comfortable with the "traveler" of the nineteenth century than with the "tourist" of the twentieth. |

||

| BIBLIOGRAPHY: Mackaye, Benton. The New Exploraton: A Philosophy of Regional Planning ______________. Expedition Nine: A Return to a Region. ______________. From Geography to Geotechnics. [A collection of 13 of his essays] Anderson, Larry. 2002. Benton MacKaye: Conservationist, Planner, and Creator of the Appalachian Trail. Johns Hopkins University Press Nash, Roderick. 1987. Wilderness and the American Mind. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press. Ness, Erik. July/August 2003. "The Path Taken". Preservation Magazine. Rubin, Robert A (ed). July 2000. "Trail Years: A History of the Appalachian Trail Conference". Appalachian Trailway News. Sutter, Paul. October 1999. "Retreat from Profit": Colonization, the

Appalachian Trail, and the social roots of Benton MacKaye's wilderness

advocacy". Environmental History. Luxenberg, Larry. 1994. Walking the Appalachian Trail. Mechanicsburg, PA Stackpole Books. |

||

|

|

||

|

STEPHEN TYNG MATHER (July 4, 1867-

January 22, 1930) |

||

|

Stephen Tyng Mather was born on July 4, 1867 and died on January 22, 1930. He is recognized as a major force in the American environmental movement. Mather began his career as an industrialist and was the president and owner of the Thorkildsen-Mather Borax Company, a mining industry centered in the west. His mining business gave him a solid income with which to ply his ideas on wilderness development. With his friend, Robert Sterling Yard, Mather began a campaign to create a new Federal program that would oversee the nation's parks. The new National Parks agency, in Mather's view would act to preserve scenic areas of the country that were quickly being taken by private purchase. Mather was brought to Washington where he was put to work creating his vision. He created the new agency, he called the National Parks agency and on January 21, 1915, he was appointed to head the agency, now called the National Parks Service and eventually placed under the direction of the Department of the Interior. As the new director of a new agency, he set about to implement many of the ideas he held regarding parks, wilderness, environmentalism, and management. When the new National Parks Service was placed under the umbrella of the Department of the Interior, the director at the time was Franklin Lane. With the department in place, Mather surrounded himself with like-minded men who promoted his vision. His vision became the persistent vision of the National Parks Service for most of it early years. In the recent Ken Burns PBS series, "The National Parks" America's Best Idea," Mather and his vision is given considerable attention and the romantic genius of this founder of our National Parks is given his due. Image from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stephen_Mather

|

||

| BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Everhart, William C.; The National Park Service; Praeger Publishers, New York, 1972 Lear, Linda. Harold L. Ickes: The Aggressive Progressive, 1874-1933 (1981) Shankland, Robert; Steve Mather of the National Parks; Alfred A. Knopf, New York; 1970 Wirth, Conrad L., Civilian Conservation Corps Program of the US Dept. of the Interior, March 1933 to 30 June 1942, a Report to Harold L. Ickes, January 1944 National Park Service Biography Guide to the Stephen Tyng Mather Papers at The Bancroft Library Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stephen_Mather "The Visionaries", by Kate Siber. [Regarding Stephen Mather and

Robert Yard and the creation of the National Parks Conservation

Association.] Full text available in National Parks, Fall

2011, Vol. 85 Issue 4, p. 1-8. |

||

|

|

||

|

JOHN NOLEN (June 14, 1869 - February 18, 1937) |

||

|

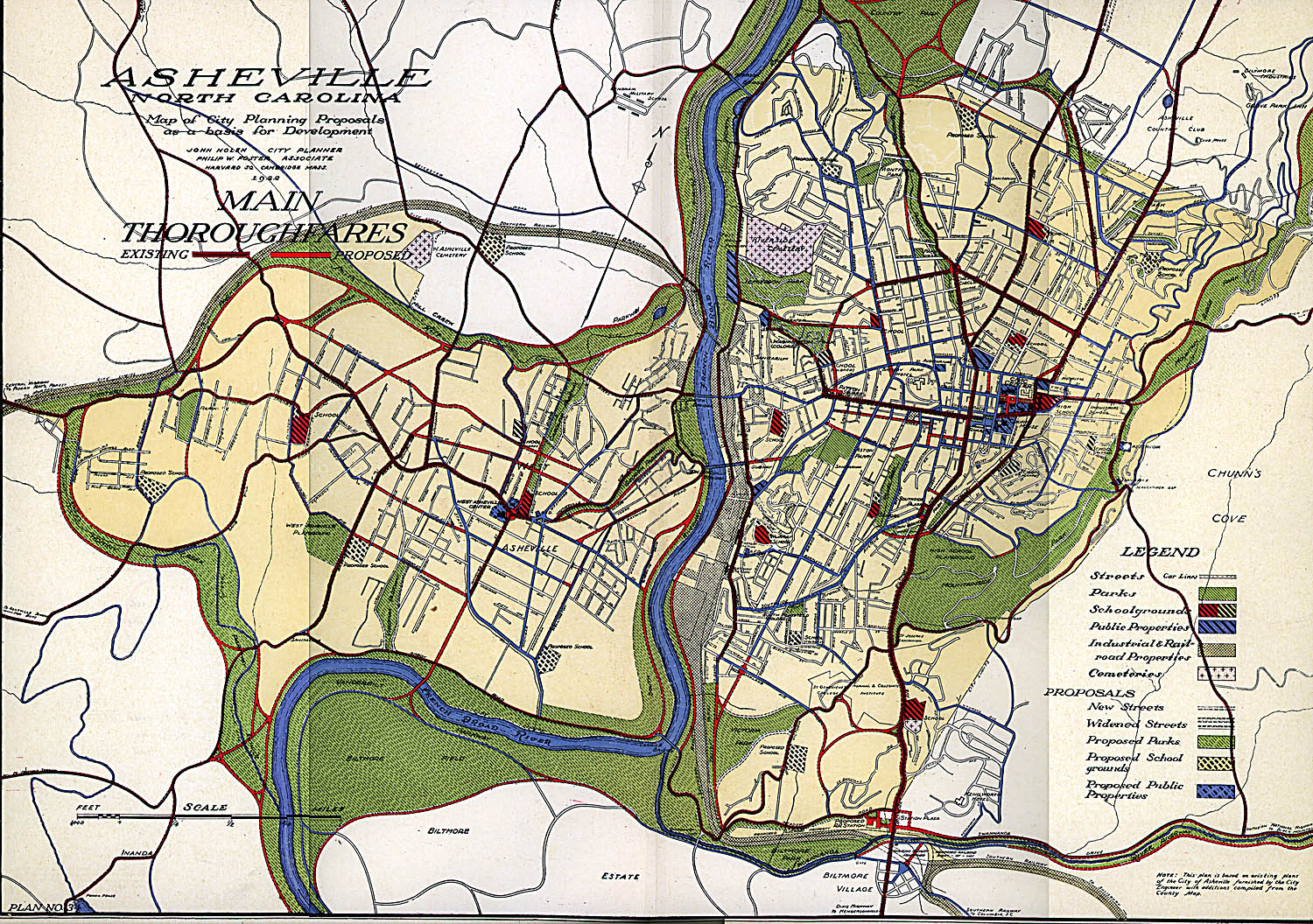

In the planning for Asheville's future, Nolen played a major role. When he arrived in Asheville in 1922 to begin the process of devising a plan for the city he declared, [Asheville] "...is on the threshold of a new state in its evolution." He saw the mountain city as a new leader in the South and a challenge to the other major metropolis' such as Atlanta. In 1922 Asheville was on the edge of the automobile age and it was the ease of access of tourists and travelers through the well established rail service and now the automobile, that Nolen heralded as the catalyst for accelerated growth. Asheville, in Nolen's plan was poised to become the center of the growing tourist traffic. He saw in the mountains, their scenery, the multitude of hotels and amenities, the possibility that Asheville could become the hub of the eastern "playground", as prime indicators of growth. Like Ickes and Hopkins, he was a regionalist who promoted the local cultural strengths of the southern Appalachians. His advice to city leaders was to curb their interest in expanding factories and instead to set their sights on "the native art and crafts industries of the mountains, such as weaving, furniture making, bookbinding, etc." [JOHN NOLEN ASHEVILLE CITY PLAN, 12-48] In his plan for Asheville he provided for twelve new parks and a series of eleven new parkways, or scenic roads on which the population could re-create. The transportation plan he outlined is seen here.

|

||

| BIBLIOGRAPHY: Starnes, Richard D. " A Conspicuous Example of What is Termed the New South": Tourism and Urban Development in Asheville, North Carolina, 1880-1925," North Carolina Historical Review, xxxxxxx Guide to the John Nolen Papers at Cornell University1926 Plan of Venice, Florida byJohn Nolen New Towns for Old: Achievements in Civic Improvement..." by John Nolen. A New Edition of a Groundbreaking text in American Town Planning. June 2005 The Roots of the New Urbanism: John Nolen’s Garden City Ethic by Bruce Stephenson. Journal of Planning History, Vol. 1, No. 2, 99-123 (2002) Madison : a model city UW-Madison TEI edition, July 2000 |

||

|

|

||

| JOSEPH HYDE PRATT

(February 3, 1870 - 1942) Geologist and initiator of the first plan for a Blue Ridge scenic highway in 1906. |

||

|

Joseph Hyde Pratt was from Connecticut where his family had settled after the Civil War. The family, largely merchants, were both wealthy and educated. Pratt attended Yale University as both an undergraduate and a graduate. He completed his Ph.D in 1896 in the natural sciences with a focus on minerals, an interest that eventually landed him a job in North Carolina as part of the North Carolina Geological Survey team. While a member of the Survey he also took a job as the Assistant to the General manager of the Toxaway Company, a successful railway and tourism business located at Toxaway in the Highlands area. It was geology, however that continued to be his life's work. In 1904 he was well-known as an expert in the field and was hired by the University of North Carolina to teach and by 1906 he was appointed as the State Geologist of North Carolina. As a geologist, Pratt was called upon to make decisions regarding road building throughout the state. He became a major figure in the state's Good Roads Association (serving as the secretary of the Association from 1905 -1920), and it was in this work that his travel and tourism experience with the Toxaway Company no doubt set him to thinking about a scenic road that would serve the tourism business in western North Carolina. Using his knowledge of the railway access to the western part of the state, his knowledge of travel and tourism, his broad familiarity with the region, and his far-reaching political contacts, Pratt set about promoting an early version of the Blue Ridge Parkway. His proposed roadway he called the "Crest of the Blue Ridge Highway" and by 1906 he had wide-spread endorsement of a plan to bring a road from the Virginia border to the Georgia border, through North Carolina. Most of the planned highway paralleled the later Blue Ridge Parkway but extended it through the mountains at Highlands, Toxaway and Sapphire. By 1912 his plan was in place and he presented it to the Good Roads Association for approval. Approval was given and construction began Construction began on July 1, 1912 near Altapass and moved southward toward the Linville Gorge area. WWI brought an end to the highway and only the section between Altapass and Pineola had been completed. Pratt's idea to develop a mountain crest highway in the Highlands area was picked up again in the 1960's by Congressman Roy Taylor and an Act of Congress almost brought the plan to construction. However, the Viet Nam War and the expense of the war intervened as did the accelerated cost of land in the Highlands area when speculators got wind of the proposed highway. |

||

| BIBLIOGRAPHY: | ||

| Joseph Hyde Pratt Papers, 1889-1942 (bulk 1915-1942). #2169, Southern Historical Collection, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. | ||

| North Carolina Geological Survey Papers (#2306); Mary Bayley Pratt Papers (#3888), Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. | ||

| Pratt, Joseph Hyde, 1870-1942 Diary of Colonel Joseph Hyde Pratt : commanding 105th Engineers, A.E.F "Reprinted from the North Carolina Historical Review with additions." in the D.H. Ramsey Library Special Collections, UNCA. | ||

| Finding Aid of the National Highway Association, Good Roads Association Records, 1902 - 1917, 1949. ORG.87, National Highway Association, Good Roads Association, North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh, NC, USA | ||

|

|

||

|

GEORGE STEPHENS (1873-1946) |

||

|

Stephens and John Nolen began a long relationship that eventually brought them both to Asheville where Stephens became the co-owner of the Asheville Citizen and was heavily engaged in real estate ventures in the city. Stephens was appointed to the City Planning Commission: along with A. G. Barnett, D. Hiden Ramsey, Harry L. Parker, and others and was in office when John Nolen presented his Asheville City Plan to the Commissioners in 1925. George Stephens was quite young when he began to have big dreams. Born near the city of Greensboro, North Carolina, Stephens was a star athlete at the University of North Carolina in both football and baseball and according to the football legend John Heisman was the first to establish the forward pass as a legitimate action in the game. Stephens moved to Charlotte after graduation and there formed a partnership with real estate entrepreneur, F.C. Abbott. The two were spectacularly successful in buying and selling houses. With their earnings, Abbott and Stephens purchased some eighty-six acres of farmland from W.R. Myers that soon became the foundation of his planned neighborhood, Piedmont Park. With the development of this land into what was essentially a sub-division, Stephens literally "broke the grid" of Charlotte. The streets of Piedmont Park followed the contours of the land and aimed for the most scenic views. Stephens also gave the Park an elite aura by establishing restrictive convenants that made it difficult --- impossible --- to be of color and to own land within the boundary of the subdivision. "...no part of said real estate shall ever be owned or occupied by any person of the Negro race." The land development signaled segregation on all levels, class, race, and economics. While Stephens was elitist is every respect, he was also a planning visionary. It was Stephens who was charged by the city of Charlotte to develop a park network in the city. He wrote to the American Civic Association and through them located John Nolen, a recent graduate of the Harvard school of landscape architecture. Stephens gave Nolen his first solid landscape job in Charlotte and later asked him to execute a plan in Henderson County for Kanuga Lake, again, a restricted private recreation complex in which Stephens had and interest. The pair began a long relationship that eventually brought them both to Asheville where Stephens became the co-owner of the Asheville Citizen and was heavily engaged in other real estate ventures in the city. Stephens was appointed to the City Planning Commission: along with A. G. Barnett, D. Hiden Ramsey, Harry L. Parker, and others and was in office when John Nolen presented his Asheville City Plan to the Commissioners in 1925. |

||

|

|

||

|

FRED L. WEEDE (1878 - ?) The illusive/elusive Fred Weede, while difficult to biographically isolate, was a central player in the North Carolina bid to bring the Blue Ridge Parkway into western North Carolina. While not a member of the North Carolina Federal Parkway Committee, the original planning committee, Weede was, nonetheless, a significant contributor behind the scenes. He claimed to be the individual who submitted the idea of a "parkway" to the Federal government, though most authorities credit Browning and Ickes for the idea. Little biographical information regarding Weede can be found other than his schooling which was at the University of Pennsylvania. His most important contribution to the history of the Blue Ridge Parkway is a 54 page autobiographical paper titled "Battle for the Blue Ridge Parkway: Being a detailed account of the long and bitter contest between the State of North Carolina and the state of Tennessee for the routing of the final approximately 169 miles of the scenic Parkway connecting the Shenandoah National Park and the Great Smoky Mountains National Park ..." . This long title sums up one of the best accounts of the intense competition for the route of the Parkway. It is filled with anecdotal information on both the inter-state competition for the parkway as well as his perspective on the later Qualla Boundary dispute. |

||

|

Weede's documentation of two of the most important political controversies of the Parkway construction gives us an excellent first-hand account of the major political battles that were associated with the construction of the Parkway. The record Weede left of his involvement is a lively and substantial first-hand account of the events that led to the creation of the Parkway, and are nuanced throughout with political intrigue. Fred was a well-seasoned politician. [WEEDE ACCOUNT OF THE BRP COMPETITION] Fred Weede came to Asheville in 1937 from Miami, Florida where he headed the greater Miami Chamber of Commerce. He was brought to Asheville to serve as the Manager of the city's Chamber of Commerce in 1938 and served in that capacity for twelve and one-half years. Unfortunately, as he notes in his memoir, the records of his tenure with the city were destroyed by his successor when he came into office. Some records, however have survived in the correspondence of other leading Asheville citizens and the flavor of his administration and personal style may be gleaned from those letters. For example, Fred Seely, the architect of the Grove Park Inn and the owner of Biltmore Industries, served as the Chairman of the Industrial Committee of the Asheville Chamber of Commerce in 1936 and later over-lapped with Weede who came into office in 1938. There are numerous correspondences between the two regarding city affairs. Regarding Weed's early life, we know that he received a B.S. in Economics in 1899 from the University of Pennsylvania, and became the General Manager of the Evening Herald in Erie, Pennsylvania shortly after receiving his degree. Sometime later he became the Publicity Director for the Miami Chamber of Commerce and soon became the Director. He was a member of the Miami Rotary Club, the Four Minute Men and participated in the Red Cross and Liberty Loan Drives during WWI. He assumed the position of Director of the Chamber of Commerce in 1938 and maintained that position until 1951. [Early biographical details from the General Alumni Catalog of the University of Pennsylvania, 1922. Weed's papers from his years with the Chamber of Commerce were reportedly burned by his successor]. |

||

| BIBLIOGRAPHY: LETTERS TO FRED SEELY FROM FRED L. WEEDE Regarding the activities of the Asheville Chamber of Commerce, D.H. Ramsey Library Special Collections, UNCA. |

||

|

|

||

|

|

||