| 02 | WHAT IS A PARKWAY? |

|

|

|

"Recreational development is a job not of building roads into the lovely country, but of building receptivity into the still unlovely human mind. " Aldo Leopold |

|

|

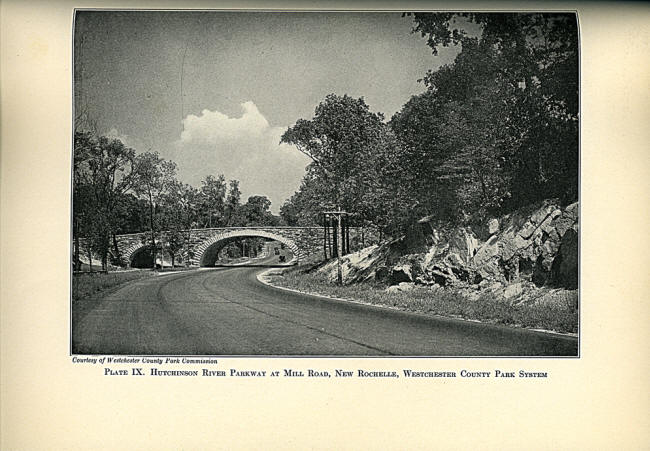

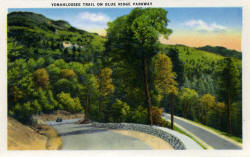

In western North Carolina when we mention "parkway" it is almost always within the context of describing our rural and scenic mountain landscape. In the Northeast when parkways are discussed, it is almost always within the context of city thoroughfares. To travel on the Blue Ridge Parkway is a very different experience than that of travel on the parkways of the Northeast. Early Origins - Westchester Parkways The earliest parkways were established in the Northeast. When construction began on the Bronx River Parkway in early 1907 it was the model for a string of similar parkways across the state of New York. The Saw Mill, the Hutchinson, and the Cross County Parkway were added to the Bronx River Parkway and by 1932 Westchester County had nearly 160 miles of parkways that also included the well-known Henry Hudson Parkway, the Taconic Parkway and the Long Island Meadowbrook Parkway systems. This extensive and integrated parkway network was inspired by the designs of Frederick Law Olmsted and the rapidly developing field of landscape architecture.

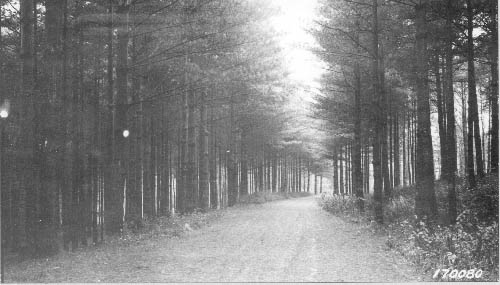

Even the work of Frederick Law Olmsted at Biltmore Estate in the late 1890's reflects his orderly, yet romantic notions of the "parkway". Here a roadway on the "Douglas Plantation" on the grounds of the estate, has all the elegance of the manor roads of Europe that were early influences on designers of park roadways.

While the new parkways were designed by the landscape architects and the early representatives are models of construction, the later iterations were too often executed by urban planners with narrow agendas and urban renewal czars, the likes of Robert Moses and others. When Virginia and North Carolina began work on their version of the parkway, the landscape architecture models were well established. Further, the similarity to urban renewal models already exercised in the Northeast, cannot be ignored. The use of eminent domain to "take" so-called "wasted land can be found in both urban and rural renewal programs. But, there are several important differences. The 469.02 (or so) miles of the Blue Ridge Parkway was not a transport system, like many of the urban parkways, but was built for the purpose of leisure driving and it was not just a parkway, it was also a large park. The Blue Ridge Parkway was partially carved out of wilderness ---- nature's wilderness, not the fabricated human jungle of the urban landscape. Parkways were, however, born in metropolitan areas. They are an integral part of the circulating system of many of our current cities. When parkways first came into being they were designed to address both circulation to and from and around cities, while providing aesthetic and recreational respite from the linear and often blighted and always congested roads that transversed the cities. The common feature of the urban parkway and the Blue Ridge Parkway is the "recreational respite" that was planned into each of the parkways. |

|

|

|

|

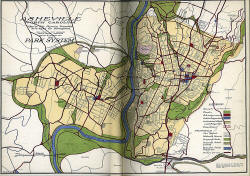

| John Nolen, the father of the 1922 Asheville City Plan, was one of the earliest landscape architects in the US to plan parkways. Nolen's 1922 plan can still be seen in small areas of the city of Asheville. His concept of small living units, self-contained with social, religious, business, and educational elements close at hand, created the sense of community throughout the city. | |

| Nolen's important book, Parkways and Land Values, conceived in 1930 and published by co-author Henry Hubbard in 1937, following Nolen's death, is arguably one of the best early treatises on parkways. It seeks to place the parkway within the metropolitan regional planning process and to assess the economics of parkways. Nolen and Hubbard's published work was with the assistance of the Harvard Department of Regional Planning and through careful analysis of planned and existing parkways, they reviewed the major features of a parkway. They analyzed the topography and occupancy of parkways, their administration, design, regulation, recreational benefits, and, importantly, their economic impacts. | |

|

John Nolen and Henry Hubbard in Parkways and Land Values, defined a "parkway" in the following legal manner:

|

|

| Gertrude Stein said "...that it is something strictly American to conceive a space that is filled with moving, a space of time that is filled always filled with moving." Whether it is a parkway, a street, a freeway, a boulevard, these threads of transportation are always filled with moving and it is in the moving along these cultural landscapes that relationships are made. It is in the process of moving that urban and rural come together, touch, and often ignite. It is where we may trace our past, our actions, and our ideas and where we may find our future, as we move along roadways such as the Blue Ridge Parkway. As rural meets the metropolitan, tensions are often formed and out of the tensions are born new partnerships, synergies of political practice, and new ways of seeing the world. In the points of contact of rural with urban along our transportation corridors, may be found lessons in evolution. In the cultural landscapes of both our parkways and our parks we can explore competing political interests, our social traditions, our understanding of aesthetics and our economic values. We can see graphically the change and continuity that accompanies the evolution of landscapes, both rural and urban | |