| 09 | ENVIRONMENT |

|

|

|

|

|

"And so, difficult and troubling as the times are, I must not neglect to say that even now I experience hours when I am deeply happy and content, and hours when I feel the possibility of greater happiness and contentment than I have yet known. these times come to me when I am in the woods, or at work on my little farm. They come bearing the knowledge that the events of man are not the great events; that the rising of the sun and the falling of the rain are more stupendous than all the works of the scientists and the prophets; that man is more blessed and graced by his days than he can ever hope to know; that the wildflowers silently bloom in the woods, exquisitely shaped and scented and colored, whether any man sees and praises them or not. A music attends the things of the earth. To sense that music is to be near the possibility of health and joy." Wendell Berry, The Long-Legged House, 1965, p.91. |

|

|

The Scenic and Healthful Route As part of the North Carolina Committee on [the] Federal Parkway, appointed by governor J.C.B. Ehringhaus and in conjunction with the State Highway Commission, a report was prepared to be presented to the Department of the Interior in November of 1934. In this report, a proposed route for the parkway was outlined and the environment was described in a manner that has remained consistent with the Department of Interior's perspective, particularly that of Secretary Harold Ickes. Secretary Ickes and others stressed the scenic and healthful nature of the route. It was, in essence, an environment to be consumed. The report section headings reflect their views:

The report is filled with romantic and picturesque narrative complete with literary flourishes and sweeping generalizations regarding the beauty of the area and its appeal to tourists.

|

|

|

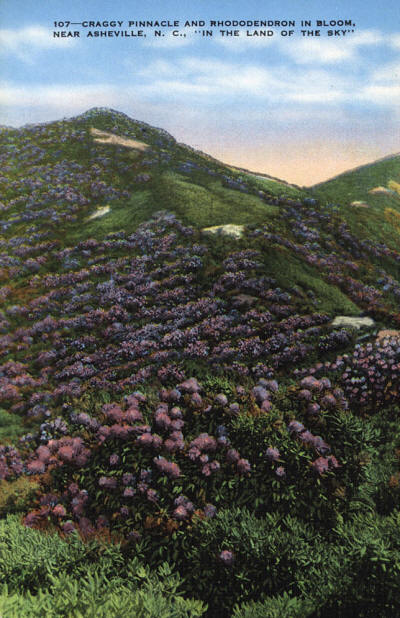

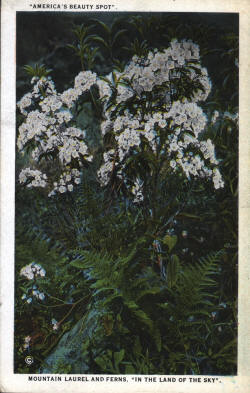

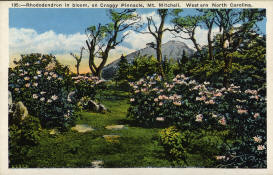

The rhododendron seen here on Craggy Pinnacle is in profusion along the route of the Blue Ridge Parkway. It blooms from June to September and can be found along the many stream beds, but also at the highest elevations, such as Craggy Pinnacle. The color of the blossoms can vary from a rose-color to a deep purple and the height of the plant can reach upwards some ten to fifteen feet. There are, in fact well over 500 flowering trees and shrubs along the Parkway route. Before July 1, over 300 of these have bloomed and following the June and July blooms, there are over 200 blooming species that may be seen later. A shrub similar to the purple rhododendron [Rhododendron Catawbiense], is called mountain laurel [Kalmia Latifolia]. "Laurel" is a somewhat confusing term in the mountains, as local people tend to call rhododendron "laurel". To further confound the nomemclature, the laurel is referred to as "ivy." Mountain laurel looks somewhat similar to rhododendron, but has a smaller leaf and is more densely packed and affords shelter for many small fauna. The dense thickets of laurel and rhododendron have been the downfall of many who tried to make early pathways into the Blue Ridge. One of the first accounts was that of Bishop Spangenburg, a Moravian who attempted to settle in western North Carolina in 1752. His venture into the mountains almost ended in tragedy when the party was lost in a thicket of laurel for days from which they had to slowly hack their way free. Both laurel and rhododendron serve another purpose along the Parkway and that is to hold the steep slopes in place. In fact many of the native plants were transferred along-side the Parkway during its construction for both the beauty and the root holding capacity of the plantings. |

"Craggy Pinnacle and Rhododendron in Bloom, Near

Asheville, N.C. 'Land of the Sky' "

|

|

|

|

|

Horace Kephart describes the forest he knew so well: .

While this rich forest growth may be glimpsed from the automobile, the best way to become acquainted with the Parkway is to leave the car and to hike into the forests. The National Parks Service in the early years characteristically emphasized the visual aspects of the Parkway. It is only in more recent years that environmental concerns, economic mandates, and travel and tourism revenues became points of focus. In the early years, unless there was a heritage site or a special topographical or biological component that warranted highlighting, the Parkway promotion was all about the scenic beauty. And, why not? Today the scenic beauty of the Parkway is still its primary attraction. But, all this beauty does not come without a price. |

|

|

In the 1963 report titled "Report of the Advisory Board on Wildlife Management in the National Parks," popularly referred to as the "Leopold Report" after it's author, Aldo Leopold (1877-1948), the preservation of national parks is detailed. This report requested by Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall spelled out the guidelines for preservation at many levels in the National Parks and advocated the re-creation of the natural ecosystem and and the natural landscapes "as nearly as possible in the condition that prevailed when the area was first visited by the white man." Leopold and others believed that a national park should represent "a vignette of primitive America." His view of 'Eden' created quite a stir among resource management personnel in the nation's parks and signaled a turning point in park management. Literally a voice in the wilderness, Leopold's views resonated with park personnel.

Leopold, who is best known as the author of A Sand County Almanac (1949), held views that are believed by some to be far too romantic. The most important chapter in this book is that titled, "The Land Ethic," which outlines a kind of mid-western pastoral idealism. His resolute pragmatism comes through when he says,

His rather romantic views are no longer held by many in the NPS, and since the 1970's, the views regarding preservation have shifted to a more pragmatic paradigm. Yet, today both the many environmental and aesthetic issues working against our national parks and the Parkway, are mitigated by the "preservationists," in the spirit of Aldo Leopold. These "Leopoldists" continue to be some of our best and most vocal watch-dogs. |

|

|

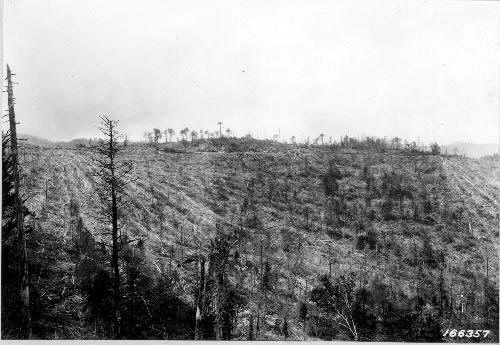

"Wasted Land" was a concept that many of those who developed the Parkway subscribed to. The idea was that the de-forested lands in the Blue Ridge mountains had yielded up their economic wealth, their timber, and that now they held little more promise for economic gain. The waste-land created by clear-cutting and extensive logging was indeed vast and ugly, but when the lumber was taken and milled, the land was not "wasted," or, non-productive. Deep in the land there were minerals and the power generated by streams was yet untapped. Tourism was still very active, even though many of the forests had been laid to waste. The "Wasted Land" anti-aesthetic concept is still alive and still working to destroy both forest and land in the Southeast. For example, over 15,000 acres of forest have fallen to clear-cutting on the nearby Cumberland Plateau. The vast holdings of government land has more recently generally spared western North Carolina from rampant clear-cutting, but in the Southeast from 1977 to 1997, thirteen of the Southern states saw clear-cutting increase by nearly 50%. Even today, by some accounts, almost two-thirds of the nation's wood supply comes from the South, not from the Northwest, as some believe. Two other devastating forces on the forests of the Blue Ridge, were the forest fires and the disease pathology of the southern Appalachian forests. Throughout the forests of the country, forest fires in the southeast led the national averages. In the mid-thirties the CCC (then called the ECW) office charged with the health of our forests, set up headquarters in Asheville where they began studies of the major diseases of the eastern hardwoods. The office sent out representatives to the CCC camps in the region where activity was underway to improve timber stands... in other words to rectify the "wasted land" in the region. The work of George Hepting, who headed the Asheville ECW office in the mid 1930's, was responsible for the firm footing of our understanding of pathological matters in the southeastern forests. Hepting's report for the CCC, found in Bulletin #2, Eastern Forest Tree Diseases in Relation to Stand Improvement, 1934 [?] outlined the extent of forest disease in the Blue Ridge mountains and beyond. The recent chestnut blight that had begun its southward march in 1912 left broad swaths of forested mountains in ruin. The fallen giants lay silent on every ridge and tannin industries in the region were devastated. |

|

|

. |

|

|

Records have not been kept for many years on the harvesting of

forests, but since 1991 it is recorded that softwood harvesting has

outstripped the net growth of this wood source. The trees targeted

for harvesting have also decreased in size and are now used for

laminated trusses and chip mill products such as paper and "chip-board".

Just in the last fifteen years (since 1987) the number of chip mills

have tripled in the Southeast. Approximately 4.6 million acres of

forests each year are harvested for these mills, and depending on the

size of the mill, the harvest can clear-cut some 7 to 10 thousand acres

of trees in one year. We can smugly look out on our "rolling sea of

forested land" along the Parkway, but we could easily see our view sheds go away if

harvesting on this scale were to be allowed in our western North Carolina forests

along the Parkway.

|

|

|

The Parkway lands have always supported a variety of flora. Recent inventories of the flora in the southeastern forests tell us that there are some 1,400 vascular plant species on the land along the Parkway and of these, nearly 25 are rare and endangered species. The Southern Appalachians are, in fact, one of the most ecologically diverse areas in the world with more than 100 varieties of trees, 1,600 plant species, 54 mammals, and 159 species of birds.

An inventory of the neighboring Great Smoky Mountain National Park by the (ATBI) All Taxa Biological Inventory project which began in 1998, has found some 907 (and counting) new species not known to science, and over 6,500 species not known to exist in the perimeter of the park. Remarkable new species of crustaceans, arachnids, algae, bees, beetles and others species have been entered into the Discover Life in America inventory, the data managing company charged with the ATBI inventory and now many others throughout the country. To view some of the many common plants that may be found along the Parkway, see the exhibit on the second floor of D.H. Ramsey Library, Native Plants of the North Carolina Mountains Suitable for Naturalization : Selected Works from the French Broad River Garden Club. The exhibit contains photographs of well-known plants from well-known western North Carolina photographers, George Masa, E.M. Ball, and Elliot Lyman Fischer. Ball and Masa are remembered for their association with Plateau Studio, a photographic studio in Asheville in the fist decades of the twentieth century. The French Broad River Garden Club, from whose collections the photographs were selected, is representative of the growing environmental awareness of organizations in western North Carolina.** The protected environment of the Parkway has a boundary of over 1200 miles and along this boundary many encroachments occur. Some encroachments include non-native species that later become invasive. Particularly troublesome are Bittersweet, kudzu, honeysuckle, and multiflora rose, (introduced in 1866 as rootstock for domestic roses). In the Blue Ridge Parkway Environmental Assessment Information Guide for Rights of Way, methods of containment are spelled out for land owners who have abutting land and serious fines are proposed for those who knowingly contribute to the spread of non-native invasive species. New fauna are also upsetting the balance of native species. The far-ranging habitat of the coyote and the rapid proliferation of the species is difficult to combat. Re-introduction of species such as the red wolf, elk, and beaver are still debated. The beaver, introduced back into the Parkway areas in 1987 are producing both positive and negative effects and the changes they are bringing to biological diversity and to the ecological processes are being watched closely by park staff . Protecting rare species within the park is serious business. For example, small reptiles such as the bog turtle, a very rare and endangered species, has a high priority with the Parkway staff. Even the species that are prolific and native, if left to populate rapidly can have adverse affects on the rarer species. The many large deer herds and the recently introduced elk have been known to threaten rare plant species in the forest due to their voracious appetites. |

|

|

Farming along the Parkway is another environmental concern. The many farms along the Parkway have begun to use modern farming methods and many of those methods while an improvement to earlier practice, can also introduce new environmental problems. For example, some haying techniques can be detrimental to water quality and to streambed sediment load, with both issues carrying long-term consequences for the environment. Many of the older farm practices were picturesque, but resulted in depleted soils and erosion. The Parkway made efforts to educate many of the farmers to good agricultural practice and their work brought much of the land back into full production. But their efforts also encouraged older practices as the rural farm was an attractive view-shed. for example, the older practice of "shocking hay" was labor intensive, but added to the local color along the Parkway. Here, some of those hay shocks may be seen in the open fields in a photograph taken by Jack Delano, a WPA photographer employed to photograph farms for the New Deal during the late 1930's and early 40's.

|

|

|

The split-rail fence was another early farm feature that Parkway officials sought to maintain along the Parkway, and some examples may still be found along the road. |

|

|

Rare and endangered plant species present special challenges for park staff as poachers of native plants and herbals become more frequent along the Parkway. Don't poach! The taking of any plant along the Parkway is illegal. Other regulations related to protecting natural life along the Parkway include:

If the violation is egregious, the fines can be $500 and as much as 6 months in jail. Regulations within the Parkway are constantly changing and many of those changes reflect the changes in our society. As we become more technology driven, new regulations must be written to protect the Parkway and its flora and fauna from sophisticated intrusion and encroachment. Recently a new regulation was written into the Code of Federal Regulations to prevent the use of recorded bird-calls played within any National Park to attract birds. While bird watchers have long imitated bird-calls, the use of electronic recording devices to reproduce bird calls has created havoc with the natural territorial imperative of many birds. For example, California spells out their concerns in their state Resources Code of regulations and mandates that this type of electronic broadcasting causes stress in the bird and may disrupt mating and nesting activity. They severely punish those who violate the Resources Code. |

|

|

"...near the possibility of health and joy ..." Wendell Berry said, "... A music attends the things of the earth. To sense that music is to be near the possibility of health and joy." Joy and that healthful relaxation does not need to be translated, legislated, or manipulated by technology, or by mediators of any kind. It only needs that one put one's foot to the earth. This action of axis mundi only requires our human imagination.

If we only let the tires of our cars touch the ground along the Parkway, we will not get the full benefit of this public gift. The automobile is not our axis mundi. To let our feet touch the ground along the Parkway, is to remember that we go into the woods to redeem ourselves, not nature. |

|

|

FRENCH BROAD RIVER GARDEN CLUB FOUNDATION COLLECTION ** For those interested in the French Broad River Garden Club and their activities, particularly their efforts to re-introduce the American Chestnut tree back into the forests of western North Carolina, join the Celebration of the Rebirth of the American Chestnut Tree to be held at the Cataloochee Ranch in Maggie Valley on September 11, 2010, sponsored by the French Broad River Garden Club. |

|

|

To view an exhibit of native flora found along the Blue Ridge Parkway that highlights plants suitable for naturalization, see:

|

|

|

|

|