|

|

||||

|

(June 6, 1831- August 31,1906) |

||||

|

A NAME THAT WILL

ENDURE |

||||

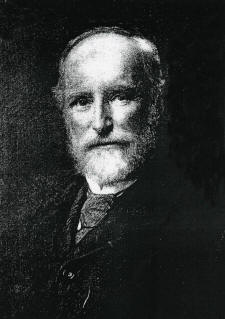

Geo.W. Pack , engraving by Bierstadt after the painting by Daniel Huntington, 1893 |

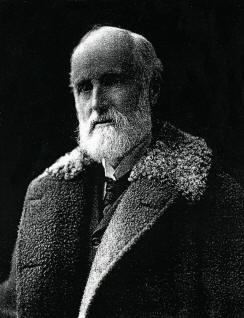

Geo. W. Pack, engraving by Sidney L. Smith of Boston, 1883 |

Geo. W. Pack, reproduction by Bierstadt after a carbon picture made by James L. Breese, 1896 |

||

| GEORGE WILLIS PACK - SORTING OUT THE LIFE | ||||

|

By Helen Wykle 100 years have passed since the death of George Willis Pack on August 31, 1906, in Southampton, Long Island, New York. Pack was born June 6, 1831, in Peterboro, Fenner Township in Madison County, New York, and his return to his home state at the end of his life seemed fitting. Yet, George Willis Pack gave some of the best years of his life to Asheville, North Carolina, and it is there that his legacy continues to expand even after his departure and his death. As the city prepares to develop and expand the small park he left to the people of this city, we are again reminded of the wonderful gift this philanthropist gave to us and of his vision for the city he called home for nearly twenty years.

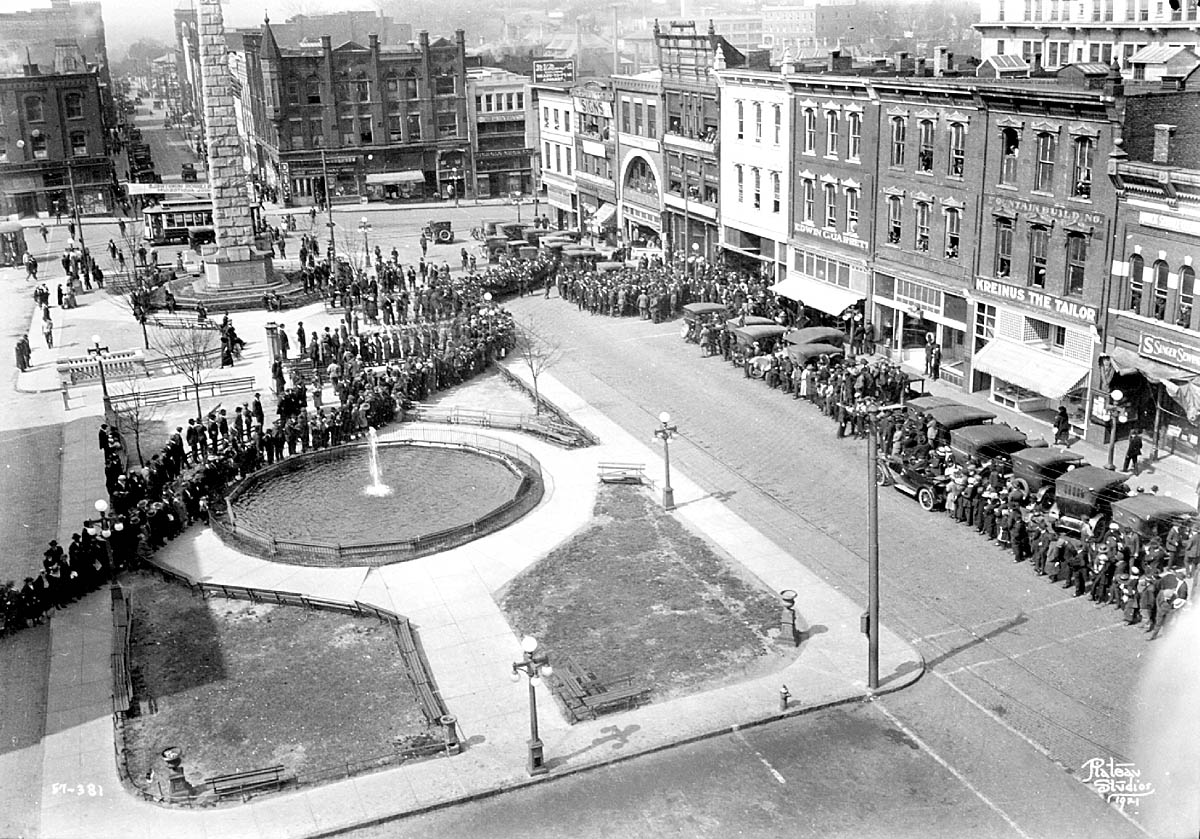

Few people who come to the mountain city of Asheville, North Carolina, can miss the open area at the cross-roads of the city, called "Pack Square." The square throbs with life as pedestrians, cars and commerce crisscross the slight hill that marks a mid-point of the city. Pack Square has always been the center of activity in this scenic North Carolina urban area. First called Market Square, then Public Square and later, Court Square for the Court House that faced the public area, the name "Pack Square" entered the city vocabulary in 1903. The name change followed the complex transfer of land from the County Commissioners to Pack and from Pack to the "people" in a DEED FOR A PACK SQUARE PARK signed by George W. Pack and his wife Frances. The deed details the provisions of the land exchange. A new Court House was to be constructed and the old 1876 court house was to be removed. In the space made available by the removal of the old court house, an open park was to be maintained for the people of Asheville. By public referendum the city honored George Willis for his generous philanthropy by naming the new space created by the removal of the old court house, "Pack Square," and George Willis Pack honored the city he had called home by creating a "park for the people."

Part of Pack's generous motivation was prompted by his desire to provide a fitting landscape for the newly erected monument to his friend Zebulon B. Vance (d. 1894), state senator and three term governor of North Carolina. The shabby and inefficient Court House that faced the monument dominated the Court Square and in 1895 Pack began thinking about a new court house and what role he might play in building one. In the complicated land purchase and later donation of land, Pack managed to enable the taking down of the old and poorly functioning Court House, to gain consensus on the construction of a new Court House and to put forward his vision of a newly transformed city. Pack appears to have always been a man of clear vision and action. In Asheville, he had the opportunity to use his accumulated wealth to put some of his visions into tangible form and in the last decade of the 1800's he set about doing just that.

The story goes that following the creation of the Vance obelisk and installation on Court Square in 1898, for which Pack reportedly paid most of the cost, there was a swap of land for a new court house between Pack, his wife Frances, and the Board of Commissioners of Buncombe County. The complex seven-page DEED dated July 24, 1901, involved a land shuffle of property Pack had recently purchased and the exchange of the land on which the County Court House stood to Pack for one dollar and the trust that Pack established between his land and the people of Asheville and Buncombe County. While the negotiations were and are difficult to follow, the resulting legacy for Pack and his family is as he must have intended it. It is a legacy that endures. The Deed reads in part

The trusteeship which Pack established passed through the family after the death of G.W. Pack, to his son, Charles Lathrop Pack and then to Charles' son Randolph Pack (1890-1956) and after his death to the second son, Arthur Pack (1893-1975) Apparently the maintenance of the Pack trusteeship ended with George Willis Pack's grandson, Arthur Pack |

||||

|

As a youth in Peterboro, New York, George Willis Pack was not schooled as one of the privileged, but attended the common school as did most youth in Peterboro. His father, George Pack, Sr. was from most accounts, a farmer, a devout Presbyterian and an industrious family-centered man. As the eldest son, George Willis learned very early that good land stewards needed to work the land as did his father and his grandfather. When the family moved to Port Huron, Michigan around 1857 when George Willis was twenty-six, the pine forests of Michigan's Madison and Sanilac Counties became the training ground and the test of his ingenuity and his endurance. Long hours of clearing ground, exploring the forests and later marketing land and timber gave him a deep appreciation of nature and of real estate. In Port Huron he and his father established one of the first sawmills, called Pack's Mills, in the Black River area of Port Huron and there made a good profit.

Before leaving New York state, the twenty-six year old George Willis married Frances Brewster Farman who came from a prominent Detroit, Michigan family. When the newlyweds came with the Pack family to Michigan in 1857, George and Frances were familiar with the state and had many contacts there. As an indication of his good connections, he was was elected to the University of Michigan Board of Regents in 1857. In 1858, the couple moved to Fort Gratiot, just north of Port Huron. The old French and Indian Fort area was also the home of another illustrious American, Thomas Edison, who knew the Packs. Here George Willis made a good profit locating and assisting others to purchase land. Another venture into the lumber business took the couple to Sand Beach, Michigan in late 1861 where he formed the firm of Carrington, Pack & Company and incorporated it in 1894. Nine years later G.W. partnered with a man named Jenks and formed Pack, Jenks & Company in Rock Falls, Michigan, a lumber business that continued even after his death until 1914. Another company, Woods & Company in Port Crescent, Michigan expanded his lumber companies even further. When Pack and his wife moved to East Cleveland, Ohio on June 25, 1870, he was a very successful lumberman and had amassed both a sizable fortune and a sizable reputation as a businessman. He soon became one of the leading citizens of Cleveland.

The family Coat of Arms contains the inscription, "Le pire ennemi du bien est la peu pres." Roughly translated, this means, "The most dangerous enemy of the good are the small things," or ".... the things that are near." Basically it reads "It's the little things that will get you ...." Keeping track of the vast real estate and timber holdings was an all consuming job for Pack, but he never let the management of his estate keep him from sharing in the civic responsibilities of the cities in which he lived. He also knew how to delegate. In Asheville his financial and real estate affairs were handled by W.B Gwyn whose two ledgers are found in the Ramsey Library Special Collections and contain personal correspondence from Gwyn to G.W. Pack and to Charles Lathrop Pack. The ledgers were donated to Ramsey Library Special Collections in 2001. Included in the ledgers are remarkable details regarding Pack and his business dealings in Asheville, particularly his real estate on the square and his involvement in the subscription campaign for the Vance Monument. George Willis Pack was a conscientious civic leader. His early education in Peterboro, a township of Fenner, New York prepared him to be a life-long contributor to the good of human-kind. His early influences included religious instruction with the anti-slavery leader and philanthropist, Gerrit Smith (1797-1874), who was associated with the Church of Peterboro, a "break-away" church which formed when the local Presbyterian church refused to condemn slavery. [NOTE from Donna D. Burdick, Smithfield Town Historian (including Peterboro), Madison County, New York.. She writes: "Perhaps George was influenced by Gerrit Smith, who did live in Peterboro, however Smith was not pastor of the Peterboro Presbyterian Church. He was a member of that church until 1843, when he and 28 others "seceded" because the Presbyterian society would not condemn slavery. Smith organized the Church of Peterboro, which was a free (or union) church."]

|

||||

|

|

Smith, a very wealthy man, chose to spend his fortune on the less fortunate

and had a vision of the world that united mankind in a common

purpose to good works.

Dr. Milton C. Sernett, Professor of African American Studies and

History, and, Adjunct Professor of Religion, Syracuse University, writes

about the

Gerrit Smith Broadside and Pamphlet Collection at

Syracuse University

It was the early influence of the abolitionist Smith and like-minded individuals that no-doubt led Pack to support Lincoln in the bid for the Presidency in 1864. And, while a member of the Michigan Legislature, and later a presidential elector during the Lincoln campaign, Pack, like Smith, demonstrated his power to persuade and to lead. Throughout his life George W. Pack remained politically well connected, persuasive, and active. |

|||

|

While Pack established businesses in many locations, he did not necessarily live where his businesses were located. The residence in Cleveland, however became a home base for he and his wife even when they finally turned to the South for health reasons. G.W. Pack came to Asheville, North Carolina in 1884, at the age of 54. He had contacts in the area and also sought a healthful environment for his wife's respiratory problems. He knew the growing reputation of the city for progressive health care and healthful and healing air. Like many wealthy Northeasterners, who sought to move their families to the mountains to get out of the increasing pollution that was overwhelming the northern cities, Pack and his wife Frances soon saw the potential for a healthy life-style in the growing city of Asheville. Just how they came to Asheville is not well known, but according to Preston Arthur in his History of Western North Carolina (1914), Pack had been encouraged by Edward J. Aston, sometimes called "Judge" Aston, to come to Asheville.

Edward J. Aston, an Asheville businessman who was well-known for promoting the real-estate of western North Carolina, possibly met Pack through mutual business associates. Both had many contacts in the lumber business. Aston who had moved to Asheville from Rogersville, Tennessee in 1853, became one of the city's most influential civic leaders and also an active land speculator. He is most likely the "Judge" referred to in an article by Edward King in Scribner's monthly magazine in 1874, in which the "Judge's" descriptions acquaint the traveler with Asheville and western North Carolina. King's article was one of the first to widely promote Asheville and the surrounding area as a desirable place to settle. Also, Pack may have found a common thread in his friend Aston's love of books. Aston became a three-time mayor of Asheville, and through his love of books, helped establish Asheville's first library.

Preston Arthur, the noted western North Carolina historian, relates that Aston was also often credited with originating the idea that Asheville would become "the sanatorium of the nation." Through the efforts of Aston and others, the first tuberculosis sanatorium was established in 1871 and the famous German tuberculosis specialist, Dr. Gleitzman, was soon enticed to the city to establish a clinic. For many years, Asheville was the "capital" of sanatoria and respiratory disease until the tourist economy eclipsed the medical economy. Growing fear of infection from the medical establishments created a widening rift in the economy in the early part of the twentieth century. Many owners began to add notices to their advertising that "consumptives need not apply," and "consumptives not welcome."

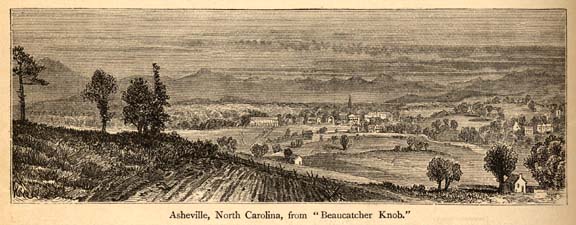

When G.W. Pack arrived in

Asheville, it was a park-like setting, but change was rapidly occurring.

The dramatic shift in population from 1880 (population 2,610) to

1890 (population 10,237) carried all the markers of rapid growth.

Forests were being decimated, the air was increasingly filled

with smoke from coal fired stoves, and water and sewer services were either

non-existent or stretched to the limit. Real-estate deals were being

made with a rapidity that staggers the imagination. This rapid growth from

a sleepy rural town to a bustling city in just ten short years can be

directly related to the arrival of the railroad in Asheville in 1880.

|

||||

|

Edward King describes Asheville (p. 505) in his

article, "The Great South: Among the Mountains of Western North

Carolina."

|

||||

| After the Pack family arrived in Asheville in 1885, they quickly became involved in civic affairs and established a large and luxurious home called, appropriately, "Manyoaks," (often written, "Many Oaks") at 140 Merrimon Avenue. While the house no longer stands, photographs of the residence show a large three-storied structure with a wide porch across the front. Today, Deal Motor occupies the 140 Merrimon location and only a grey granite wall reminds us of the Pack home. | ||||

|

|

||||

|

George Willis Pack was a member of many clubs and served in various civic capacities. We can thank him for his efforts to electrify early Asheville. He became the primary advocate for placing electric lights in the town square and also for paving the streets and constructing more sidewalks for pedestrians. He also worked to develop an improved sewer system and stated that he believed that Asheville would benefit from encouraging more indoor plumbing. He donated funds to support and build the Swannanoa Hunt Club which later became the Country Club and eventually the Grove Park Inn club. The Swannanoa Hunt Club was one of the first clubs to support a golf-course in North Carolina. It was followed by only a few years, by the Linville Golf Club, in Linville, NC, built in 1895. Pack was an active member of the Asheville Club and the Swannanoa Hunt Club and apparently delighted in activities that took him out-doors.

The generosity of G.W. Pack is legend. Besides the court house land, he donated a building for the Asheville Free Kindergarten and paid the salary of one of the teachers. This generous act was reportedly prompted by the numerous "ragamuffins" he saw on the city square. He also, reportedly, assisted in the development of what was then and now known as Mission Hospital. He gave approximately eleven acres of land for Aston Park on South French Broad Avenue, dedicated to his friend "Judge" Edward J. Aston, who had encouraged him to come to Asheville. The fourteen acre park today continues to serve the community in a variety of ways. It is nationally recognized for its tennis courts, reportedly the greatest number of clay courts of any mid-sized city in the U.S. |

||||

|

In Montford he gave the land for another park, Montford Park.

The Montford Park donation was approximately four acres of land and was

among only a handful of parks available in Asheville in the first decades

of the twentieth century. In addition to his gifts of land, Pack donated one of his prime buildings, the former First National Bank building [previously, Trust National Bank Building] to the Asheville Library Board to house the Asheville Public Library. Asheville's library wandered from home to home until the collections were consolidated in 1899 and placed in the donated building at the southeast corner of Court House square, later Pack Square. |

"Spring-time in Montford Park" (and009) , Stafford and Wingate L. Anders Collection, D.H. Ramsey Library, Special Collections, UNC at Asheville 28804 |

|||

|

|

Even consolidated, the collections were due to

be moved again when Pack's building was removed and was replaced in 1926 with

a white Georgia marble and Neo-Classical

structure, somewhat to the left of Pack's donated building. Today this structure

with many additions, houses the Asheville Art Museum, the

Health Adventure and the Gem and Mineral Museum. The library

collections were moved yet another time in 1979 to the new and expanded building on Haywood Street.

Today, the Haywood location is home of the Asheville-Buncombe Library

System and holds the historical collections of the city as well as

providing library services to the general population. Long committed to education, Pack supported the schools and this included the schools for the African American community. He paid the salaries of two teachers at Beaumont Street School, the first public school for African Americans that had opened in 1888 and reportedly had some 300 children in attendance. |

|||

|

Throughout most of his later life Pack was well known as a mentor. His counsel and his wisdom were remarked on by many. In one of the accounts of his life, a small booklet entitled "Life of George W. Pack," from America's Successful Men, published and privately printed in Cleveland, Ohio in 1898, his character is put forward

|

||||

| W.B. GWYN, LAND AGENT FOR GEO. W. PACK | ||||

| The letters of Walter B. Gwyn are some of the most

intimate accounts we have of Pack's years in Asheville and the various activity

and events

surrounding Pack's real estate interests. The competition for land was

fierce during the years following the completion of the railway into

Asheville. The many property swaps, "big-deals" and railroad fever can be

traced in the papers of W.B. Gwyn. In the some 2000 letters by Gwyn can be

read the extraordinary growth of a city. As he wrote to G.W. Pack and to

his son, Charles Lathrop Pack, the letters of Gwyn trace the events

surrounding the Vance Monument subscription initiative, the negotiation for the construction of a new court house on land

donated by G.W. Pack, and multiple other real-estate and financial

intrigues. Two ledgers of letters in the Ramsey Library Special

Collections contain Gwyn's correspondence from 1891 to 1897. Walter B. Gwyn's early business contacts were impressive, if the two ledgers in this collection are any measure. He was integrally instrumental in the building of the city through his legal negotiations for various clients. Real estate negotiations at the end of the nineteenth century and continuing into the early twentieth century in Asheville were rapid-fire and included many of the major so-called "Robber-Barons" in the north east. Also, in 1886 Gwyn had a Gold Mining Company located in Henderson County. The Boylsten [Boilston] Creek area of Henderson County was thought to have a large deposit of gold bearing quartz. In the Ores of North Carolina, 1887, p.316, we read, “Explorations were so favorable that a company was formed to work it [the mine], and the proper machinery erected for treating the ores.” The mining company Gwyn created was called Boilston Mining Company, and was incorporated under Cert. #59, in 1886. Walter B. Gwyn was the President, and the secretary was P.S. Cummings. Initially, Gwyn successfully sold shares in the company, but it did not turn out to be the "large deposit" that was first thought and mining returns did not sustain the company. It quickly fell into hard times and Gwyn moved on to other ventures. Like so many of the entrepreneurs at the end of the century, Gwyn's prospects and those of his clients began to dim in 1896 when personal debt began to pile up, many, including Gwyn, found themselves over-extended. He wrote to his brother James M. in December of 1896 that he was without means to re-pay his debts and that the Great Panic of 1893 had left his fortunes ruined. Gwyn and many others watched as stocks tumbled and railroad investments disintegrated. What happened to Gwyn, is not unlike the events before the Crash of 1929. Asheville had been in a feeding frenzy of land speculation from the mid to late years of the nineteenth century and Gwyn's ledgers are filled with accounts of speculative "deals." Land that can be had by buying "cheap" and quickly selling "high" was proffered to the highest bidder and the frantic pace of buying and selling is often difficult to follow in Gwyn's correspondence. The prosperity of the land boom in Asheville in the early part of the 1880's and 1890's led to a false sense of well-being. Land monopolies in Asheville such as those of George Willis Pack, Henry Phipps, the Vanderbilts, the Pattons, the Davidsons, the Merrimons, the Coxes, and others was not an exercise in planned economy, but one of opportunity that eventually ruined all but the very rich. While the very wealthy prospered, new entrepreneurs such as Gwyn, often found their over-zealous buying eventually brought them into crushing debt and personal ruin. In one letter to his family Gwyn laments that his assets in the early years of his life were recorded at over $100,000 and at the end of his life his debts were well over that amount. The "boom" and "bust" cycles seen in Asheville in the later years of the nineteenth-century and the early years of the twentieth-century have been repeated on a small scale, again and again as the city grew. Prosperity and decline and again prosperity was the case of Gwyn and such was and is the history of Asheville, generally. |

||||

|

While Gwyn may not have left a monetary fortune as his legacy, or large

civic enterprises, he has given

Asheville and Buncombe County something equally precious, his historical

reflections. Contained in the two ledgers in the UNCA Special Collections, are numerous accounts of his

work with G.W. Pack and other entrepreneurs and investors, and from these accounts,

we can begin to piece

together a first-hand account of the events surrounding two of Pack's most

important donations --the some $2,000 Pack contributed toward a monument for

Zebulon Vance to be placed in Court Square [later Pack Square] and the

donation of approximately four acres of land for a new courthouse, the

1903 County Court House, and an accompanying park where the old court

house had been removed --- Pack Square.

|

||||

| "THE WICKEDNESS AND FOLLY OF INTOLERANCE ..." - THE VANCE MONUMENT | ||||

|

The seed money for the Zebulon Baird Vance Monument is one of George

Willis Pack's most intriguing donations to the city of Asheville. The tall obelisk constructed of grey granite was completed some four years

following the death of Governor

Zebulon Vance (1830-1894), a Weaverville native.

Its location in Court House Square was agreed to by the subscribers and

the people of Asheville and local architect, Richard Sharp Smith was

contracted to design the monument. Over the years it has seen varying amounts of

attention from those who use the square. Annually, for many years, a ceremony was held at the foot of the

obelisk to remember Vance and his many contributions to North Carolina. The

monument also alludes to many of the things that were important in Vance'

life. The Egyptian obelisks with their cryptic hieroglyphs is referenced

in the shape of the monument. Rulers throughout the world brought many

of the Egyptian monuments back as trophies of their wars. The nineteenth

century had a particular fascination with Egypt and the

literature of the day is filled with references to all things Egyptian.

Egyptian symbolism also figures prominently in the lore of the Freemason.

Vance was a

life-long Mason and participated in the Mt. Hermon Lodge #118 l in Asheville,

as did many of Asheville's leading citizens. While the allusion to Egyptian monuments seems clear, the allusion to a particular related ideology is less clear. Recently, some have referred to the monument as Asheville's "monument to tolerance." [See Steve Rasmussen, "Asheville's Monument to Tolerance, " in Mountain Xpress, 1999.]. The Rasmussen article discusses Vance's political life and his commitment to humankind and suggests a relationship to his Masonic brotherhood. Allusions are intended to mean many different things to many different people and it is perhaps to the monument's credit that its plain and stately reach for the sky can take on a variety of meanings. The tall grey pillar is part of the landscape of Asheville, and stands as a marker for the heart of Asheville, yet few people when asked, can recite any of the history behind the creation of this memorial sculpture, particularly the role George Pack played in its creation. The essentials of the story are these. George Pack reportedly paid some $2,000 dollars toward the development of the monument and assisted in the subscription campaign to raise an additional $1,300 from other contributors in the city. There is no doubt that Vance was deserving of the monument. He had earned considerable reputation as a Senator and as a three-term governor of the state of North Carolina. His picture and name shows up all over the state. The history books carry many stories of his life. For example, it was Vance who nurtured the state through the bloody years of the Civil War. It was Vance who maintained civil law in the state when the chaos of the Civil War was tearing other states apart. It was Vance who adeptly negotiated the complex tax structure of the state and it was also Vance who was imprisoned by the Secretary of War for rather murky reasons following the war. It was a magnanimous decision of the Federal government to let him out of the "Old Capitol Prison" when it was revealed that Vance has assisted in obtaining food and clothing for Federal prisoners at Salisbury, North Carolina. The humanitarian act toward Federal prisoners in his own state was persuasive evidence that parole would be the most humane compromise to his dilemma. [See (1907. Ashe, Samuel. Biographical History of North Carolina..., Vol. VI, p.490.) |

||||

|

|

||||

|

Perhaps as a child growing up in Peterboro, New Jersey, George W. Pack learned "the folly of intolerance," in the teachings of Gerrit Smith, the noted abolitionist. His early education with Smith in the Presbyterian church was surely influential. Or, maybe it was Smith's guidance combined with the injustices of the Civil War that moved Pack to a more liberal stand on racial and ethnic views. But, at some point in his life he came to a belief in the idea of one humanity. This tolerant view was at the center of his character, as it was in the character of another important western North Carolinian, his friend, Zebulon Vance. However, the two views took the leaders in two very different directions. Pack, an elector for President Lincoln, was every thing the Union stood for during the War. Vance, while he began by canvassing for the Union, the first shot into Fort Sumter convinced him to shift his sympathy to the Confederacy and "his own people." He said of his new allegiance, that "If we had to slay, I had rather slay strangers than my own kindred and neighbors." Vance and his "Rough and Ready Guards" filled Public Square and marched against the Union even before the state convention adopted the ordinance of secession. What then, fostered the bond of friendship between these two civic leaders of two different political persuasions? Even before Fort Sumter was fired upon, Vance had clamored for a tolerance of views. Though he shifted his allegiance after Fort Sumter, his stance during the war was generally one of moderation. His well-known gift of oration made sure that his views had a wide audience and his gifts of persuasion were legend. Both were used to keep North Carolina from succumbing to the division and chaos seen in many other southern states. Vance, like Pack spent a lifetime seeking to bring people together and working to advance his state. One of his most famous statements on tolerance was in a speech he authored known as the "The Scattered Nation" (1916) speech. In the speech which he gave numerous times, in various forms, to many engaged audiences, he put forward an impassioned plea for a more tolerant view of the world. |

||||

| Some believe his speech to be a tribute to his

close Jewish friend and Masonic brother, Samuel Wittowsky, a Polish-born

Jew from Charlotte, NC. Wittowsky and Vance formed a close bond while they

both served as lawyers in Charlotte. When Vance died, Wittowsky carried

him to his final resting place in

Riverside Cemetery in Asheville, just as he had carried him by carriage to

Washington when Vane was imprisoned at the end of the war. Legend has it

that Wittowsky offered his carriage for transport when Vance had

difficulty in seating his portly body on horseback to make the long

trip. The trip, reportedly cemented the relationship of the two men. Wittowsky and Vance

and possibly Pack

were all members of the Freemasons. Vance, as noted earlier, was a member of the Mt. Hermon Lodge #118 in Asheville,

which was eventually in 1913, located in the Richard Sharp Smith building,

the Scottish Rites

building, on the corner of Broadway and Woodfin. It is uncertain if Pack

was also a member.

In the "Scattered Nation" speech, Vance quotes a passage from a certain Professor Maury that likens the Jewish people to the Gulf Stream that runs through the oceans of the world, but never mingles. While this allusion may run counter to some of our contemporary ideas of diversity, his point was intended to be encompassing and respectful of the Jewish need to remain separate, but equal, and to awaken the public to the accomplishments of this ethnic group. His comments in the speech run in part

For many years the Asheville chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy along with the local chapter of B'nai B'rith conducted a joint ceremony at the Vance Monument. This shared ceremony is testimony to the overlapping bonds that Vance fostered during his life-time. It is evident in the many accounts of his life that Vance had a great sensitivity to the plight of all men. This deep empathy for fellow-man was obviously shared by George Willis Pack. |

||||

| PACK, PIGS, DIVAS, CONESTOGAS, ROADS & THE RAILROAD | ||||

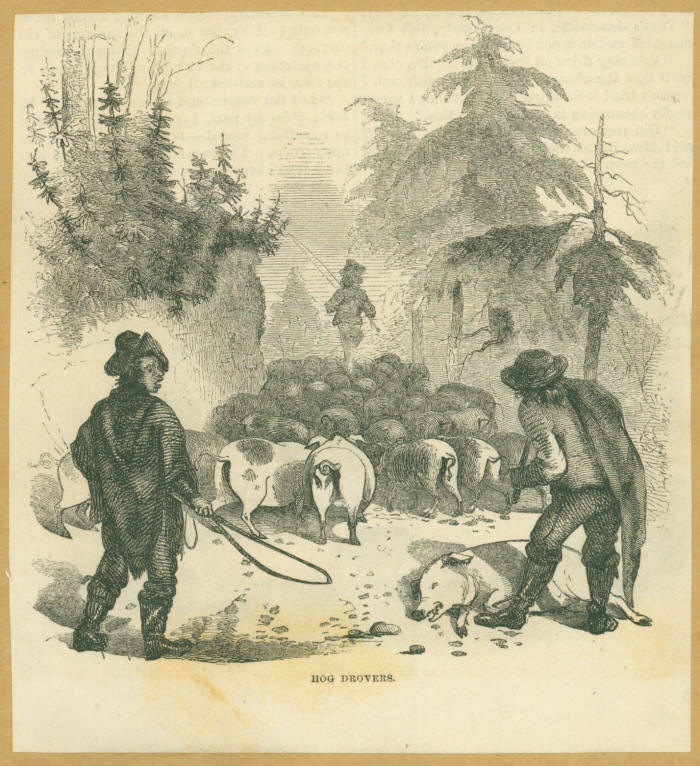

The Drover's Road, later the Buncombe County Turnpike, established a

pattern of movement through the city of Asheville. The course of animals

and humans right through the center of town often left deep pig-wallows,

mud up to the thighs of men and horses and, most likely, an unbearable stench on hot summer days.

But, it also left a pattern of movement that centered the north-south

route and the east-west route on the slight rise that is today Pack

Square. John Nolen, who was hired to develop a city plan for Asheville in

1922, said that Asheville's Pack Square had always been the geographical

center of the city and no matter how the city may change, it would

probably remain the city center.

In the midst of all the "messy" and odorous commerce of the early era, the city of Asheville yearned to be something more. Following the Civil War, during the Reconstruction era, many southern cities looked for ways to celebrate their growing wealth and their "culture. In 1876 the citizens of Asheville created an Opera Hall in the third floor of their new court house. By all accounts it was a great success and attracted a range of performers from vaudeville to the divas of opera. Atlanta had the Kimball Opera house before 1868 but the largest and most famous of the opera houses in the south east, the Grand Opera House in Atlanta was not built until 1883-1884, some years after the Asheville opera house. The Newberry Opera house, near Charleston was not built until 1882. A complete accounting of the programming for Asheville's Opera House, has yet to be assembled. |

||||

| ROADS AND THE BUNCOMBE COUNTY TURNPIKE | ||||

|

|

||||

|

Roads were the single most important element in the commerce of Asheville

and those roads and commerce structured much of the city as it exists today.

The most famous of the roads was the so-called Buncombe County Turnpike

which was approved by the state legislature in 1827 as a toll-road, and

which carried tens of thousands of drovers and their livestock from Kentucky and Tennessee

through Asheville to markets in South Carolina and Georgia.

The roads quickly improved following the production of the automobile. By the 1920's Asheville and the surrounding area were remarkably prepared for travel by auto. According to Drummond's Pictorial Atlas of North Carolina, [Albert Y. Drummond], published in 1924 by Scoggins Printing Company of Winston-Salem, NC, Buncombe County "had more paved roads than any county in the South and the projected area of paved streets in Asheville was expected to be the greatest area of paved streets in the United States for cities of comparable size. However, when G.W. Pack arrived in 1884, the city was still trying to negotiate many unpaved and muddy streets. With the arrival of the railroad, the roads through Asheville took on more importance and Pack worked hard to bring Asheville into the mainstream of city transportation. The central artery for north-south travelers led many tourists through Asheville and the to the west of the city. This route took travelers to what was then called the Atlantic Highway. Going to the east, the traveler would also cross Asheville to connect to the two main highways that were gradually improving and extending across the state and were well traveled by those wishing to travel to the coastal regions. |

||||

|

|

||||

| To honor the Drovers and their herds of animals, a local artist Margery Torre-Godwin, has created a series of bronze pigs and turkey's situated on a curving path marked with foot-prints in the square just below the Vance Monument. This sculptural group is one of a number of monuments, sculptures, and art-works that artists contracted by the Asheville Area Arts Council provided to the city. There are some 30 art-works throughout the city on a 1.7 mile Urban Trail. | ||||

|

|

||||

|

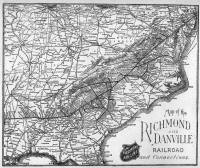

Following the Drover's Road and the Buncombe County Turnpike, the next milestone in transport was the railroad. The year 1880 marked the completion of the railroad into the city of Asheville and its connection with the growing rail system that was tracing a web of commerce across the southeastern United States. . |

||||

| THE RAILROAD | ||||

| The first train pulled into the Asheville

depot on October 3, 1880. The expansion of rail service to the mountain

town was the catalyst that Asheville needed to expand both commerce and

tourism. The large jump in population seen between 1880 (2,60) and 1890

(10,237) is testimony to the importance of rail to the development of the

city. W.B. Gwyn's small venture in local rail was only a part of the

expanding network of rail lines that would soon make Asheville a

cross-road in the Southern Railway system. After 1880, numerous brochures,

booklets and guides were published by the railroad promoting Asheville as

a tourist destination. Among those is

Roger's

Asheville and

Western North Carolina R.R. Scenery,

"Land of the Sky", and

Souvenir of Asheville or the Sky-Land,

1892. In Rogers Asheville we read

When the last leg of the rail line was completed into Asheville in 1880 service to a large section of the Northeast and the Southeast was enabled. The Carolina, the Clinchfield and the Ohio Railway systems by 1924 were the arteries that led to the major cities and the Cincinnati-Columbia division with the connectors running through Murphy to the west and Salisbury to the east brought large numbers of tourists and commerce into the area. |

||||

|

|

|

The Sunny South: Some Interesting Drawings by E.H. Suydam |

||

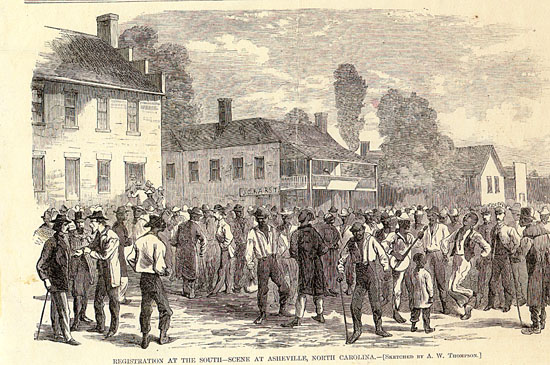

| In 1867 Harper's magazine recorded the Negro Registration to vote on the square in Asheville. This well-known sketch by A.W. Thompson, provides rich visual information on the population and on the political climate in Asheville during the years just following the Civil War. [See UNCA student paper by Jenny Wallace. "Making Congregation out of Segregation: the African American Culture and Community in Asheville, early 20th century," 2003, Senior History Paper, UNCA for a discussion of turn of the century segregation in Asheville.] | ||||

|

|

||||

| Where Pack Square is concerned, there are few

neutral opinions. Like many common spaces in our cities, the use of

park space and open space is often contested. Perhaps the most contested issue

surrounding Pack Square is the long held belief that George W. Pack willed

the space to the people of Asheville and that the people should be the arbiters

of its purposes and its uses. The uses and the purposes, like the people,

have been argued for and rejected, fought for and accepted, and

occasionally, hoped for and received.

What George Willis Pack was clear about was the need to serve the needs of all the citizens of the city and county and he set about constructing a document that would serve as a cornerstone, for a space that he hoped would help to build community. George Willis Pack did indeed will the area of Pack Square to the people and his generous gift is recorded in DEED [DB122/21] held in the Buncombe County office of deeds and records as of August 5, 1901. Because few have seen the full deed, the context of the quote "... hereby forever dedicated to a free and unobstructed public use." has often been misconstrued to suit the purposes of the many particular "publics." The full context of Pack's deed is, in fact, remarkably ambiguous, if Pack himself was not. It is this ambiguity of reading that has given writers, politicians, artists, trustafarians, neocons, vendors and just plain folk the foundation for much of their contention. While our reading of the Pack deed may present some challenges, the reading of the history of the space and the space itself are two other types of "read." If we are tuned into our visual process, we often "read" public spaces. We size up a place based on our walk through the space and we fill it with our allusions. The language of public spaces and of landscape generally, is an area of study that we are just beginning to understand. Reading space is a very cross-disciplinary process. It challenges the walker and the scholar to integrate in the most liberal way, the various parts of the "reading." For this reason, the space, we call Pack Square has often been contentious space and one well appreciated by those versed in the "liberal arts" and those adept at the informed leisurely stroll. It is history, sociology, art, psychology, popular culture, and more. Public spaces in general, have often been contentious. What we put in the space, what we bring to the space and take away, and what relationship the space has to its borders and periphery can create many points of conflict. Many spaces come to mind that have similar points of conflict. One, the placement of a large contemporary sculpture called "Tilted Arc" in the Federal Plaza of New York by Richard Serra, resulted in substantial debate on the use of public space. The work was eventually removed after a bitter fight over the rights of the artist versus the rights of the citizens who used the space. We often draw borders around the familiar not recognizing that our familiar is not the same as another's "familiar." As communities seek to share their diverse perspectives, and as individuals seek to find their identity, public spaces have often become the forum for trying out new ideas. Some ideas have been sustainable, and some have not. And, some ideas will be sustainable and some will not. |

||||

| DEDICATION OF THE COUNTY

COURT HOUSE, 1928 The changing ideas, ideologies, and allusions related to the court house space may be traced in the historical account of the court houses given in the dedication program notes written by A.F. Sondly for the new county court house. In this short history of Buncombe County he provides a snap-shot of the progression of the court houses and a snap-shot of the public spaces they occupied. [A Brief History of Buncombe County by F.A. Sondley, L.L.D. "Excerpts from a paper prepared for the ceremony of the laying of the corner-stone for the New Court-House, November 7th, 1927.] |

||||

The account reads in

part

|

||||

| DOUGLAS ELLINGTON AND THE CITY HALL DISPUTE | ||||

| Not only do our open spaces generate debate, so too, our buildings. One of the most memorable debates regarding buildings in the city of Asheville, is connected with the so-called "Ugly Twins" that sit on the periphery of Pack Square. Visually there is a failure to communicate between the two buildings. One, a Neo-Classical and traditional government structure, and the other, an Art Deco wedding-cake of a building. The story of how these two building came to be, is a story of great interest and also of on-going debate. The correspondence related to the details of the construction of the two buildings may be found in the Edgar M. Lyda Collection in the UNCA Special Collections and in files held at Pack Library. | ||||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

||||

| The political debate

regarding the County Building is briefly described by the following

account. The construction of the two buildings became complicated by

politics and poor communication. The progressive art

deco structure already designed by Douglas Ellington and completed and

dedicated March 19, 1928, was scheduled to have an adjoining structure

that would be used by the county. Ellington, after some discussion with the mayor,

Edgar Lyda, assumed that he would be the architect of choice to design the

County Court House. Following some intense political

maneuvering, the contract for the work was given, not to Ellington, but to

Milburn & Heister. It is in the disparate style of these two buildings, that many people today hang their allusions. City and county, rural and urban, conservative and liberal, have become points of departure for considerable debate and dispute, but fundamentally, the two structures provide a point and counter-point to central discussions we continue to put forward as the city seeks to find its "voice". The two building, together reflect the active "spirit" of this unique city. |

||||

| ALLUSIONS AND MORAL

SPACES - THE PUBLIC AND PUBLIC

SQUARES |

||||

| The language of a place is often the language

of the person or people who create the space. Probably no one has been

or is more

instrumental in the creation of Pack Square, than the public to whom Pack

dedicated the space and who daily re-invent the space. Those who have used

and have adapted the space over time have given every support to the

belief in a "public trust." "Landscapes" says Ann Whiston Spirn, who writes about language and landscape, are full of allusions. They remind us in an indirect way, of persons, or places, or of work or recreation. To allude to something pre-supposes that there is shared understanding and that those who share have a common knowledge. That common knowledge is most often, our history. But, who, when they visit Pack Square, can tell us of George Willis Pack? The rare few. Do the visitors to Asheville's central space know that the "Pack" alludes to a man who helped shape many parts of the city, not just the square? The Vance Memorial, the tall obelisk that dominates the square contains numerous allusions --- to the Civil War, to diversity, to our Biblical history, and to our many "Scattered Nations." But, few know those histories. Chains of allusions can often consolidate an idea. Today we read many things into the spaces we use and certainly into Pack Square. Today the Vance Memorial shares its space with bronze turkeys and pigs, and with "Trustafarians" and "Neocons". The cynical terms we use to describe the young tattooed neo-hippies who live on the trusts set up by parents and grand-parents, or the morally conservative Republicans, often dubbed neocons come to the park with their own set of allusions. All are welcome. Who is to say that one person's allusion -- or illusion -- is better than the others? The "Crossroads," bronze sculptures, the work of artist Margery Torre-Godwin, are allusions to the Drover's Road that came through the square in earlier times. Thousands of turkeys, pigs, cattle, horses, geese, and other farm stock had to be fed and around this demand a new economy grew, based on the production of food stock for the thousands of animals and for the boarding of travelers. Perhaps George Pack wanted to be associated with the revered Civil War governor, Zebulon Vance and by that association, or allusion, to make his connections to the area and the area's people. Perhaps Pack wanted the allusion to Vance's liberal stand on diversity to be associated with his own interests in creating a diverse city. Whatever the reasons, Pack worked to build many allusions into his created park and into the DEED that supported those allusions. Reading those allusions takes skill in reading, not just the documents, but some education in interpretive visualization. In literature, we often find common experiences with the characters in the literature. The many descriptions of Pack Square all share a pride of place and by placing our stories within a common textual framework we can share in those stories and they can give significance to our lives. For example, The Conquest of Canaan, a silent film from Paramount Studios was shot in and around Asheville's Pack Square in 1921 and is filled with allusions. It tells the story of a young man who is struggling to find his identity in a small town and explores the natural and moral state of individuals in a small town who are both conquerors and conquered. Like Booth Tarkington's novel of the same name and like the moral tale of John Martin's Conquest of Canaan, which was the inspiration for Tarkington, the film reads like a series of moral lessons from a father to his son.. The story was filmed in downtown Asheville, N.C., in and around Pack Square, the old Courthouse facing College Street and near the First Baptist Church at the corner of Spruce and College Streets. The old Swannanoa-Berkeley Hotel, later the Earle Hotel, was used as a backdrop and renamed the "Canaan City Hotel" for the film. Streetcars, signs, and other landmarks were re-named for the film and hundreds of extras were hired for the large scenes, particularly the mob-scene on Pack Square. |

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

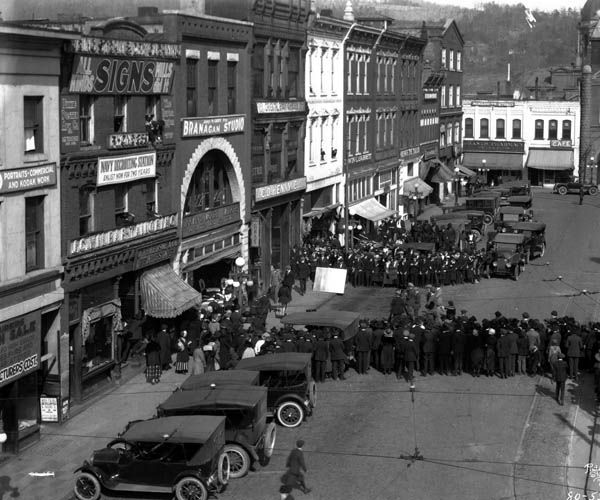

| In Herbert Pelton's photograph of the extras

in front of Branagan's Studio, on Pack Square, we are removed to the year of 1921 and the

allusion of life as it was or might have been in Asheville. We can see

beyond the small town America that Tarkington tried to capture in his

novel. And, in the film, we can marvel at the visual allusions captured by

Director Roy William Neill, as he translated Tarkington into a silent

montage of corruption and morality. The Russians took the Paramount film

to their country sometime in the 1930's or 1940's to show their

people what life in American small towns was like. While the visual

images may have been novel, the allusions to their own moral dilemmas must

have resonated.

When Asheville views the Conquest of Canaan it rarely sees the homogeneous "Our Town," viewed by the Russians, but instead sees our town, the buildings, the square, the Vance Monument. We relish in the allusions to another time and delight in the views of our familiar places as they appeared in the first quarter of the twentieth-century. Yet, we share with the Russians, the allusions to our own shared moral dilemmas. Through the camera lens of photographers such as Herbert Pelton, George Masa, Ewart Ball and the movie camera lens of Neill and others, we can imagine Pack Square in another time. The photograph freezes the moment in time, but alludes to the energy of place and the inner space of our intangible dreams. |

||||

| THE "PLAIN PLEASURES" of JOHN NOLEN | ||||

John Nolen was once asked why should cities

have public parks. He responded by saying that parks have a practical

role, in that they can raise the level of the real estate on the periphery and can keep urban blight to a minimum. He also added that parks can have

the advantage of keeping the wealthy content and from moving out of the urban

areas. In his article "The Parks and Recreation Facilities in the United

States," for the Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social

Science, Vol 35 No. 2, Public Recreation Facilities, (Mar., 1910), pp.

1-12, Nolen laments

Today, the attendance of our National Parks is on the decline and the attending to electronic entertainment is on the rise. The rise in the virtual experience suggests a shift in the way we are "reading." our environment. If John Nolen is to be believed, parks are a necessity in the city. If Nolen's plan had been fully realized, the whole city would have been a park, yet Nolen's idea of "park" was not necessarily the tree shrouded walkways and open green-spaces we may imagine.. The main purpose of a park, says Nolen is to enhance natural beauty and for recreation, while contributing to pleasure and health of urban populations. "Park" as Nolen defines it includes, city squares, public gardens, commons, and playgrounds. He further suggests that city parks need to be developed with an understanding that they are systems. And, as a system, each of the parts must have a relation to another part. What Nolen advocated was a system of city planning. Asheville was only one of many city planning projects that he undertook and Sarasota, San Diego's Balboa Park, Charlotte, and Roanoke are but a few cities that are more livable after his thoughtful recommendations. |

||||

| In 1922 Asheville contracted with John Nolen

to evaluate the city and to provide a well defined city plan.

The

Asheville City Plan, 1922, is that plan. "City planning," said

Nolen in the Annals article, "is, therefore, an effort to save

waste -- waste due to thoughtless delay, to hap-hazard procedure and to

ill-considered plans. When city planning is wise it works in harmony with

local conditions, takes account of topography, and responds to the

peculiar social and economic influences of the locality."

As noted earlier, Nolen understood city planning, but he was less savvy about natural landscape. He failed to fully understand the role of native vegetation in the city plan and seemed to be more comfortable in making nature conform to the plan than in planning around natural spaces, all the while envisioning the city as a park. Trees, particularly fell victim to Nolen's plan -- not to the extent that was seen in Nolen's revisions of Balboa Park in San Diego, where large numbers of trees were removed from the canyon slopes to provide "views" from the plateaus, but he relegated greenways in Asheville to the periphery of the city. In many ways Nolen's plan for the city exemplified the "Nature" versus "production" thesis put forward by Henri Lefevre in his book Space. Lefevre contends that space is an "open receptacle," into which is poured the contents of our allusions and ideologies. He observes that "the more a space enters into the social relations of production," the less likely it is to pay attention to nature. Correspondingly, the more fore-grounded the social relations of production, the more decline is seen in nature. The decrease in the visitors to our national and state parks is likely an indication of this phenomenon. The growing dependence on the virtual experience has taken the audience for nature further and further from this realm. Paul Virilio has painted a gloomy picture for us in one of the essays in his Landscape of Events. He says of this virtual world

The world in which we now live is one of instantaneous transmission. It is a world driven by the social relations of production and by the spectacle of calamity. A story is told of an old man who when asked to say what is the world's greatest calamity, replied, "the news." Paul Virilio, the harsh critic of our modern life told this story and added

This world that Virilio describes is one in which the individual is isolated from the active world of sensory experience, the park, the forest, the river, the flower. It is a world devoid of the knowledge of the space that surrounds the body. If we are to urbanize in real space we need to understand this space in relation to the inertia of real time -- what is in essence, the end of the outside world. Parks can bring us back to an understanding of self. They can help put us in touch with the language of landscape --- the discriminating gaze, and the language of our own bodies. In many ways the park space is a social relationship between its many discreet parts and it is a product meant to be "consumed." But, it is also a "means of production" (Lefevre, 1991). Parks produces space that is organized according to a social superstructure -- a montage of play, oration, spectacle, fountains that are allusions to mountain streams, aural feasts of music (Mountain Dance and Folk Festival and Shindig on the Green), and education {the projected Pavilion). By studying the content of the space of the Public Square, the Court Square and Pack's Square, we can begin to understand our history and culture in Asheville and with the creation of the new Pack Square, we can begin to shape our space, to produce space that heals, entertains, and informs. We can reshape a space that signals commodity and money or one that contains the dialectal relationships between city and countryside and between social reality and natural reality. After all, Pack gave the square to us. |

||||

| TRACING THE LEGACY -- THE G.W. PACK CHILDREN | ||||

| MARY PACK AND CHARLES LATHROP PACK | ||||

|

George Willis Pack and his wife, Frances Farman Pack had four children, Charles Lathrop Pack (May 7, 1857 - June 14, 1937), the eldest, and Mary Pack (September 23, 1860 - November 14, 1939), Millicent (February 22, 1865 - November 3, 1865) who died in infancy, and Beulah Brewster (August 27, 1869 - ? ) . Mary Pack was born at Fort Gratoit, Michigan and later married Amos McNairy. It is Mary who has left us the most intimate account of the family. In her brief "Memories," either written by her or dictated to her family at the end of her life, she captured the early years of the family while they were living in Sand Beach, Michigan.

Mary Pack McNairy's "Memories" give the most telling picture of the G.W. Pack family and the forces that shaped the parents and the two children during their years together. Either written or dictated in her last year of life at the age of 79, Mary's brief memoir is quite detailed regarding the family while they were at Sand Beach, Michigan. She recounts the quaint routines of the family at the turn of the century, speaks admiringly of her mother's courage and assertiveness, remembers events with family members and friends, and recalls the tragic forest fire that nearly destroyed the family home and business. She relates

|

||||

| CHARLES LATHROP PACK (1857-1937) - PHILANTHROPIST AND CONSERVATIONIST | ||||

| Charles, like his sister Mary was enchanted by

nature. The early years of living at Fort Gratoit, near Sand Beach kept

Charles close to the land and to nature. Like his father and his

grandfather, he began his career in the timber industry, but he

took another direction with his interest.

Charles was born in Port Huron, Michigan on May 7, 1857. He was educated in Cleveland,

Ohio where the family had moved in 1870. Following this early education

in Ohio,

he went to the Black Forest area of Germany where he studied forestry in

the developing program offered by the Germans. One of the first young

men to be trained in forestry, he quickly gained a reputation in the

field. Jay

Gould, reportedly the wealthiest man in America at the time of his death

in 1892, contracted Charles to evaluate his forests. The large fee that

Gould paid Charles was the first time a forester had received a fee for

work of this nature and the association with Gould, his obvious

knowledge of forestry, helped to establish Charles'

reputation across the country. His friend Dr. Arthur Adams, Professor of

English, Trinity College, Hartford, Connecticut contributed a credible

essay on the many accomplishments of Charles Lathrop Pack during his

life. It is found

in a small privately printed family genealogy, provided by the family of Pack to the Pack

Conservancy and is possibly taken from the larger publication by Charles

Lathrop Pack, Thomas Hatch of Barnstable & some of his

descendants; the descent of Alice Gertrude Hatch and her husband, Charles

Lathrop Pack, from Thomas Hatch and allied families. Newark,

N.J., The Society of Colonial Wars in the State of New Jersey, 1930. It reads in part:

In his book, The War Garden Victorious (c. 1919), in the chapter WAR GARDENS AS CITY ASSETS, A Thing of Beauty Is A Joy Forever, Charles Lathrop Pack, is obviously inspired by the City Beautiful Movement that prompted many early nineteenth century cities to re-evaluate their public spaces. The Movement, which began in England, found a very sympathetic audience in nineteenth century American architects and landscape architects. Following the World Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, many architects, city planners, and landscape architects such as George Kessler, John Nolen, Calvert Vaux, Frederick Law Olmsted, Charles Mulford Robinson, and Daniel Burnham, championed the international movement. Many forward thinking cities saw in the transformation of their landscapes, city streets , public spaces, and in innovative architecture, the opportunity to expand their economic base by attracting business and commerce. Space was for these early entrepreneurs both nature and commerce. Charles Pack took the ideas related to parks found in the City Beautiful Movement a step further and noted that parks that were active, that engaged people in productive activities, could collaboratively contribute to the war effort while encouraging civic pride and community spirit.

While President of the American Forestry Association in Washington, D.C., Charles prepared a small booklet called "Memorial Trees," in which he lauds the memorial tree. He says to his audience

The idea for the Memorial Tree movement grew out of the need to provide some fitting memorial to soldiers who had served in WWI. The movement also extended to Europe where the devastation to the forests in Belgium, Great Britain, and Italy are well known. The forest authorities in the a number of European countries worked with Pack and with the American Forestry Association to send saplings and seed to Europe to begin the re-planting process. Thomas R. Marshall, Woodrow Wilson's Vice President, said of the Memorial Trees program

|

||||

|

Pack's ideas regarding forest conservation resonate well today and due to his early efforts numerous cities were improved by their tree-lined streets and many parks were planted with trees that today are majestic in size. Through his campaign many of our trees have been preserved and maintenance of our forests has improved. He said of the future for memorial trees and forestry in general

|

|

|||

|

Another of his publications, Trees As Good Citizens,

published in

Washington, D. C.by the American Tree Association [c1922], is further

testimony to Charles Lathrop Pack's commitment to forest ecology and to

conservation, generally. |

||||

The Book of Clevelanders, A Biographical Dictionary of Living Men of

the City of Cleveland, Burrows Book Company, 1914 provides this

listing for Charles Lathrop Pack:

|

||||

| GRANDCHILDREN, GHOST RANCH AND GEORGIA O'KEEFE | ||||

| ARTHUR PACK (1893 - 1975) - EDITOR AND PHILANTHROPIST | ||||

|

Arthur Pack (1893-1975), the son of Charles Lathrop Pack, also distinguished himself as an environmentalist. His chosen career, however, was as a publisher. His story continues the enduring connection with Asheville's Pack Square and the family's commitment to environmental awareness. Importantly, he continued his father's work following his death and various environmental centers and educational institutions such as the Center for Sustainable Forestry at Pack Forest, University of Washington, benefited from his direct memorial contributions. Many of Arthur's letter to Dean Hugo Wikenwerder, the Director of the Center are held at the University of Washington. Additional letters may be found at the Charles Lathrop Pack Collection in the Terence J. Hoverter Archives at the State University of New York, College of Environmental Science and Forestry.

Arthur Pack was born on February 20, 1883 in Cleveland, Ohio. He attended Williams College a liberal arts college in Williamstown, Massachusetts, and from there went to Harvard where he studied Business Administration. When the war came, Arthur was first stationed at the US Ordnance Department in Washington, D.C and later went to England and to France where he served in various capacities as a Captain of Ordnance. While in England he worked with the war effort to develop tactical uses for airplanes in the war. Following the war, he came back to work with his father in a variety of tasks. He soon turned his many skills into several careers. As a former editor of Nature Magazine, Arthur Pack continued the family interest in the environment and became very active in national efforts to preserve the environment as a forest conservationist. He founded and headed the American Nature Association of Washington, D.C., and ensured that his father's work would continue by establishing the Charles Lathrop Pack Forestry Foundation.

In the 1930's when he was in his late 30's he bought a ranch in New Mexico, near Santa Fe that he called "Ghost Ranch," also in 1936 he married Phoebe Finley. The two of them went to Ghost Ranch to live and it is there they began a family. The ranch was both a home and an investment as a "dude ranch." It became famous through one of its more famous visitors, Georgia O'Keefe. In fact, Georgia O'Keefe became such a frequent visitor that she came to lay claim on her "cottage" and on one of her trips to the ranch she found the cottage had been rented to someone else. The story goes that she became unhappy that "her" cottage had been released and sat down with Arthur to work out the purchase of approximately four acres of the ranch, including her "cottage."

The New Mexico "dude ranch" was not a financial success and in 1941, Pack invested in a second "Ghost Ranch," this time in Tucson, Arizona. This second site was largely a lodge which he called "Ghost Ranch Lodge." In 1946 he moved his family to the lodge in Tucson and only returned to New Mexico for vacations. 1955 Arthur Pack gave his New Mexico "Ghost Ranch" ranch to the Board of Christian Education, Presbyterian Church, USA. Today it is used as an education center and as a retreat for the church.

Like his father, Arthur's profile was low-key. He preferred to keep his philanthropy a quiet process. And, like his father, he contributed to the community in which he lived. His development with William Carr of the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum was made possible largely through funding from the Charles Lathrop Pack Forestry Foundation and Arthur's funds. The Museum became a focus for him in the last years of his life and also spawned another similar museum which he supported in New Mexico, called the Ghost Ranch Museum near, Abiquiu, New Mexico, founded in 1959. His participation on many boards in Tucson was instrumental in shaping many of the city's important social programs. He participated in the Tucson Chamber of Commerce, the Tucson Child Guidance Clinic, United Way, the House of Neighborly Service, the County Parks and Revreation Commission, the YMCA, United Way, and as Chairman of the Board of Trustees for St. Mary's Hospital. For his outstanding contribution to the community, Arthur received the Tucson "Man of the Year" award in 1952 and in 1968 the Kalish Award from the Jewish Community Council for outstanding leadership in conservation. In 1974 he was awarded the Association of Interpretative Naturalists annual award. He held several honorary degrees, including an honorary doctor of laws degree from the University of New Mexico and an honorary doctor of science degree from the University of Arizona. In a tribute to Arthur Pack's generosity and his sensitivity to the environment, Morris Udall once noted, "If I could wish one blessing for each community, I would ask that each be blessed with at least one Arthur Pack." His partner in the Desert Museum initiative, William Carr said of him, "... He was always ready to stand up for his views and to back them up with his philanthropy." He also noted that Arthur was not one to preach his ideology, he simply practiced it.

|

||||

| PACK SQUARE - THE MANY FACES OF ITS ARCHITECTURE AND ITS PUBLIC | ||||

Catherine Alexander in her article in Signs, Spring 2002 v27 i3 p857(16), discusses "The Garden as Occasional Domestic Space," and tells us much about gardens as space. The garden, like a park can be enclosed by the many faces of architecture and commerce such as that seen in Pack Square. Each of the spaces has special qualities. While the intent of Alexander it to discuss "gardens" her interpretations have a particular resonance for those who use parks and squares. She says

What is markedly different in Alexander's garden, is its "occasional" nature. Pack Square endures, but its "nature" is occasional and it is about to change again. Pack Square was donated with the intent that it would endure and it will most likely endure through the coming years. But, it will also change. What will change and what has changed in a very marked way is the border to the space we call Pack Square. Buildings have come and buildings have gone away. This march of real estate we can well count on as a moving periphery, a "leaky" boundary to the cosmos within.

|

||||

| CLOGGERS AND PICKERS -

THE MOUNTAIN DANCE AND FOLK FESTIVAL & SHINDIG ON THE GREEN |

||||

|

|

|

||

An ongoing tradition on the square is the Mountain Dance and Folk Festival. The Festival (MDFF) is the nation's oldest folk festival. It grew out of the Rhododendron Festival and by 1930 it was an independent festival in Asheville, North Carolina. Today the annual Mountain Dance and Folk Festival continues to feature musicians and dancers who characterize the music and dance of the Southern Appalachian region. In 2003, the Folk Heritage Committee donated the archive for the Festival and for the Shindig on the Green to UNCA. This collection of material, the archive of the Mountain Dance and Folk Festival and its subsidiary entertainment venue, the "Shindig on the Green," is currently being processed by Special Collections at UNCA and the digital material will continue to be added as it is scanned. The Folk Heritage Committee, a subcommittee of the Asheville Chamber of Commerce is the governing organization charged with the management of the Festival and of the Shindig on the Green and the records in this collection were donated by that agency and record their activity from the late 1960's to the present. The very early history of the Mountain Dance and Folk Festival is included in the archive of Bascom Lamar Lunsford held by Mars Hill College, North Carolina and in various private collections. Some early records and correspondence is included in the collection at UNCA, though the largest body of material is the visual material that grew out of the marketing efforts of the Folk Heritage Committee and the Asheville Chamber of Commerce. The photographic images, the posters, programs, ephemera, and some objects such as award cups, plaques, and framed awards is concentrated on the 1970's through the 1980's and depicts many of the events and performers of the Mountain Dance and Folk Festival and the Shindig on the Green and may be accessed in the Special Collections at D.H. Ramsey Library. |

||||

Narrative written and posted online in 2006 by Helen Wykle, Coordinator of Special Collections. Helen Wykle retired from UNCA in 2012. This website had minor updates and revisions in 2017. Many thanks to the following for their contributions to the original 2006 exhibit: Suzzy Sams (UNCA), Donna Clark (PSC), Jamie Patterson (UNCA), Nancy Hayes (UNCA), Ann Wright (ABLS), and Zoe Rhine (ABLS). |

||||

|

|

||||