| 05 | POLITICS | |

|

|

||

|

||

|

While the muckraker Steffans was very hard

on the government and their enchantment with politics, it was during Theodore Roosevelt's administration that

many of the ideas fundamental to the Blue Ridge Parkway were born.

But, it was also during this administration that the idea of political "muckraking"

arose. The term, reportedly first used by Roosevelt, is taken from the muckrake in Bunyan's Pilgrims's Progress

where

the citizen looked "no way but downward, with a muckrake in his hands." Lincoln Steffens,

one of the most well-known muckrakers, or political pundits, took on the

early corporate establishment when he wrote an article titled "Tweed Days in St. Louis,"

which addressed urban

political corruption and the role of urban blight in the degradation of

our cities.

Theodore Roosevelt loved the mountains of western North Carolina and came several times to the area to both campaign and to recreate. The courthouse in the image below is the old Court House of Asheville that was replaced by today's City Building and County Courthouse. Roosevelt came to Asheville to campaign in 1902. |

||

|

[ball2114] Theodore Roosevelt addressing crowds at Pack Square, Asheville, NC, 1902. |

||

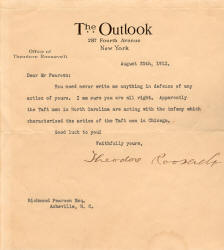

In 1912 Theodore Roosevelt wrote to

Asheville's Richmond Pearson who was running for office, regarding his

political observations of North Carolina politics.

|

|

|

|

Calling on the Appalachian heritage, authors made icons of virtue out of the mountain cabin. Robert Lindsay Mason, the author of The Lure of the Great Smokies, wrote, "The frontier cabin of America should be emblazoned on her coat of arms," He believed it to be "the emblem of the American, because it is like no other cabin on earth; that it appeals to every true American and awakens visions of upstanding men, fearless fighters, determined homemakers, invincible republic builders. "At once it [the cabin] suggests danger,

hardship, endurance and courage; it suggests clean -mindedness and good

citizenship," said Mason. The many famous Americans born in

these cabins were then named by Mason: Jackson, Lincoln, Boon,

Shelby, Robertson, Crockett, Houston, Blount, Custer, McKinley, and

Xavier. The idea of the frontier leader was never far from the

romance of the mountains and its rustic cabins. It is little

wonder that the cabin was integrated into the view sheds of the Parkway.

Where it did not appear naturally, it was fabricated, or brought from

other locations to add confirmation of this great American icon of

virtue. |

||

|

When Muckrakers like Steffans and other politicians looked to the countryside and to the agrarian communities as havens of sanity and common sense, they were following the common threads woven by politicians down through the years. The need to escape the corrupted city was a much expressed sentiment during the first two decades of the twentieth century. Cleaning up the urban mess was high in the minds of many who lived in the industrialized hearts of America's metropolitan areas. Congestion of city thoroughfares, pollution, poor air quality, immigrant issues, economic divides, graft, corruption, were all ideas Steffan's and others associated with the city and its money driven industries and businessmen. Finding ways to introduce bucolic and healthful living into the city was part of the charge given to landscape architects. Teddy Roosevelt did not turn a deaf ear to this rage for reform. He too, saw wilderness as a salve for this savaged city soul. It was during his administration that the seeds for environmentalism were sown and the cornerstone of the national park system was legislated. Speaking of a visit to the Great Smoky Mountains, he said:

The political tussles concerning the Parkway centered on three very contentious issues, all regarding the route of the Parkway. The first contentious political issue was the main one --- whether the parkway should follow a route into North Carolina or should pass through the neighboring state of Tennessee. The second major political sticking point was the desire of the government to run the route of the Parkway through the Cherokee Indian Reservation in the Qualla Boundary and to pull the cultural capital from that ethnic group into the travel and tourism mix. The desired route was to come down the mountain and to run through the main street of the reservation. The problem was reaching agreement among the Tribal members and the members with the Federal government. It was a lengthy process. The third route issue was the last and the most protracted, that of the Linn Cove Viaduct construction around Grandfather Mountain. TENNESSEE OR NORTH CAROLINA ROUTE? On October 17, 1938 a meeting called by Senator Harry Byrd was set to discuss the 'proposed' route of the parkway. At this time there was no firm agreement regarding the final route of the Parkway, nor was the Parkway yet given a name. Representatives from all states that had a stake in the parkway plan were present and all were asked to speak for their constituencies. Smaller committees were formed and all states, Virginia, North Carolina, and Tennessee began the process of developing proposals for the route of the parkway. The process was remarkably quick, but not clean. Virginia's stake in the parkway was certain. The new parkway would begin in Virginia where the earlier Skyline Drive ended and then continue its path through a combination of North Carolina and Tennessee, or entirely within one or the other of the states. Before the final decision was rendered by Harold Ickes, the two states, Tennessee and North Carolina engaged in a lively and sometimes heated political debate. |

||

|

Interior Secretary, Ickes, going against the recommendations of the Parkway committee, chose North Carolina as the preferred route. In his justification he cited the previous generous government subsidy of TVA which went mostly to the state of Tennessee and noted that the Parkway allocations to North Carolina would balance the budgetary considerations for the two states, by giving North Carolina a fair share of the New Deal funding. He was careful to say that both states had scenic capital of equal measure, but that the pivotal concern was focused on financial equitability. |

Robert Doughton, 1942. [Wikipedia Media, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division ] |

|

|

Another important influence may have been the presence of Robert L. Doughton (1863-1954), Democratic congressman from North Carolina, who served as Chairman of the very influential House Ways and Means Committee. Doughton was born in Alleghany County, NC which stood to benefit substantially from the North Carolina route. It has been noted by many that he wielded a strong hand in creating the Parkway and securing funding for the road. Doughton Park, one of the most used public parks along the way is named for the influential Congressman. Governor Ehringhaus place Doughton on the nine member task force, the North Carolina Committee on the Federal Parkway, who ere charged with devising a plan for the route. Chaired by J. Quince Gilkey, the committee had several influential Washington contacts, including the powerful Senator Robert R. Reynolds of Asheville, and the astute businessman, Ruben B. Robertson, the President of Champion Fiber Company, located just outside Asheville. |

||

|

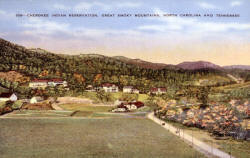

THE QUALLA BOUNDARY ROUTE. When initial planning was underway for the parkway, two routes were proposed. The first plan was to take the parkway from Virginia into North Carolina, down to the Lineville Gorge area and from there over the Roan Mountain into Tennessee where it would cross into the Great Smoky mountains and serve the large urban center of Knoxville, a thriving city that saw itself as the gateway to the Smokies. The second proposed route was one which would serve the prospering tourist mecca of Asheville. This urban center would have a stretch of parkway running to the south of the city and would make the city an even more desirable destination. Both proposals, the Qualla Boundary route and the Tennessee/North Carolina route kept government officials busy and state lobbyists hopping around to offices of Congressmen and Senators in Washington for many months. When Fred Bauer, Vice-Chief of the Eastern Band of the Cherokee testified before the House Committee on Public Land regarding the Weaver Bill (Establishing the Blue Ridge Parkway, pp. 74-75) he bitterly said that the government was trying to "landscape the Indians into the park entrance ... for the entertainment of rubber-nedked tourists." This acrimonious outburst by Bauer is one of many such desperate word-storms levied against the government for their handling of the right-of-way for the closing segment of the Blue Ridge Parkway planned to run through the Qualla Boundary and to end at Oconaluftee on the reservation. Fred Bauer and his wife Catherine Bauer were two of the most outspoken opponents of the government plan and their campaign against the parkway and the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) became so strident that George Stephens, the owner of the Asheville Citizen and the Times at the time, sent a notice to his paper and to others to not print anything the Bauer's sent to the paper. There is evidence that the Raleigh News and Observer and the Charlotte Observer took the advice of Stephens ... (so much for the 'free' press!). The saga that pitted the Bauers against the government is one of the most colorful and paradoxical chapters in the construction of the Blue Ridge Parkway and one that bring to the foreground the many issues -- often paradoxical surrounding the Cherokee and their relationship with the US government during the early thirties and later. The burning question with the Qualla Boundary and the construction of the last leg of the Blue Ridge as it ended at the doorway to the Smoky Mountains National Park was not one question, but many. Whose interests did the parkway serve? Whose parkway would it be when completed? Was the parkway even necessary? The attempts at answering these questions brought to front of the debate all the classic cultural and class conflict debates. The politics surrounding the parkway's route through the Qualla Boundary has been briefly described in the section of the exhibit, entitles "Politics", but the issues are much deeper than just "political" and complext from both the government and the Indian side. Negotiations began with the Cherokee in the mid-thirties but it was not until 1940 that the tribal council reluctantly approved the route for the parkway to pass through their territory and granted the right-of-way for the construction of this last leg of the North Carolina route. |

||

|

The Qualla Boundary, centered in Jackson and Swain Counties is geographically the North Carolina doorway to the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The park, newly created in the 1930's is sandwiched on the edge of two competitive states that both have interests in claiming. the Cherokee are also sandwiched between two large and often competing park systems; the Blue Ridge Parkway and the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The lessons in travel and tourism learned from their neighbors gave the Cherokee the opportunity to develop their own travel and tourism industry. On this fact all parties in the geographic area were agreed. |

[Click for larger image] Cherokee Indian Reservation, Great Smoky Mountains, North Carolina and Tennessee LeCompte Postcard Collection, D.H. Ramsey Library. Special Collections, UNCA |

|

|

On most other facts, there was disagreement. The clear need to generate an income to sustain the some 2200 Cherokee who were living in the Qualla Boundary in the 1930's was accepted by all, but the means of income generation was in dispute. How to maintain their identity and their traditional way of life with so many new encroachments became one of the most compelling conundrums. A review of the literature produced for the travel and tourism industry during the early years of the Parkway clearly defines the issues. Indians in feathered headresses, and the use of "squaw" and "papoose" and "Indian scouts", suggests a lack of understanding of the Native populations and a clear exploitation of a non-existent life-style. |

||

|

Since the 1830's when the tragic Trail of Tears removal program decimated the eastern Cherokee's way of life, the tribe struggled to reorganize and find their place again in the mountains of western North Carolina. Following removal the tribe managed to negotiate the purchase of some 60,000 acres of land and a charter that legalized their status as a Cherokee tribe. They succeeded and established a Tribal Council that would guide their people. The charter they had negotiated with the state of North Carolina defined them as a corporation yet their status as an Indian tribe placed them under the jurisdiction of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). The struggle between state and federal agencies put a strain on the already fragile fabric of the tribe during the Blue Ridge Parkway debate as some in the tribe aligned with the state and others with the BIA and the federal government. |

||

|

Fred and Catherine Bauer did not necessarily align with either legal entity but others in the tribe did and one key figure, the Tribal Chief (1955-1959), Jarret Blythe, established a strong relationship with John Collier, the former director of the Bureau of Indian Affairs until his administrative appointment to the New Deal cabinet. Collier has been described as a 'regionalist' romantic who, like Ickes saw in the Native American a return to our origins and a pristine life-style that honored preservation and homage to our cultural past. |

||

|

|

||

|

LINN COVE VIADUCT - "Beginning of The End. The Missing Link" Following this early failure to purchase the area, discussions continued sporadically with the focus shifting from negotiations for land acquisition and price, to the level of outright dispute when right-of-way was introduced. The disputes became a long-term issue when no compromise seemed acceptable to the owners. The back-and-forth became very political regarding the route on Grandfather Mountain and when land deeds were acquired in 1939, they had to be adjusted by the state in 1955 to another proposed route and yet again in 1957. Concerns continued on environmental issues, cost, and the disputed route claims and misunderstandings from years past until May 2, 1963, when the North Carolina Highway Commission recommended a route that was acceptable to all parties. Many of the details of the construction of the Linn Cove Viaduct are found in the extensive report prepared by the National Parks Service, the HABS/HAER Report, July 2001, to accompany the official Historic American Engineering Record historical report on the Blue Ridge Parkway. This report prepared by Kelly Young, written by Brian Cleven and edited by Tim Davis, is the most extensive record of the Viaduct, its planning, design, construction, and use. On Friday September 11, 1987, fifty-two years after ground was first broken for the Blue Ridge Parkway, the long, 469.02 (or so), miles were completed by the Linn Cove Viaduct. Milepost 1 to Milepost 469 were finally joined as one continuous parkway. |

||

|

|

||

_small.jpg)

%20(Custom)_small.jpg)

%20(Custom)_small.jpg)

%20(Custom)_small.jpg)