| 08 | DIVERSITY |

|

|

|

|

|

|

An exploration of the diversity issues associated with the Blue Ridge Parkway reveals substantial class and cultural differences at work in its creation, use, and future. Even those early planners who seemed the most enlightened with regard to human rights and social reform, failed to grasp the deep divides between the diverse populations touched by the Parkway. While it might be observed that "those were different times" some of the failures were clearly associated with class differences and long-standing cultural prejudices related to race and gender that continue to be a part of our national psyche. African Americans, women, Native Americans, and poor Appalachian mountaineers, were all marginalized by the prevailing racial, ethnic, gender and class issues in place in the early Parkway years. Many of those cultural and class identity issues continue to be points of considerable critique and debate, even today. This cultural conversation is a healthy process and one that has greatly expanded our understanding of diversity issues both at the local level and at the national level in this country. |

|

|

The census of 1940 tells us that about 980,000 African Americans lived in North Carolina and approximately 660,000 were living in Virginia. Within the area of the Blue Ridge mountains the numbers of African Americans was small, but the potential for travel and tourism from this population was great.

|

|

|

Both the cultural interest in the lives of African Americans and their potential as consumer were recognized by the Parkway developers, but when the Parkway was completed, this segment of the population either did not use the Parkway or were re-buffed by Parkway regulations. The reasons for these tensions are not easy to understand and cannot be attributed solely to racial relations but also grow from community relations. In one account, that of the oral history of Mary Jones, a resident of Ashe County, NC, we learn a great deal about the early negro populations of Ashe County, on the Virginia border where the Parkway came through. Jones in her interview with Dr. Louis Silveri speaks of the lives of African Americans in the rural communities around her, particularly the former slave families and their relationship with the local people and community..

Page 33 - 35 D.H. Ramsey Library Special Collections, Oral History, Mary J. Jones, UNCA Jones tells Silveri about the population near Creston, where she lived. : Jones goes on to describe a very close relationship of the mountain families with the former slave families:

A 1939 Parkway document, referred to in the literature of the Blue Ridge Parkway as the "Negro Master Plan," is part of the original planning for construction of the Parkway. It gives a clear picture of the sentiment of those master architects, landscape planners, and other project leaders, of the role of African Americans in the construction process as well as on the user or tourist side. Robert G. Hall is named as the associate landscape architect who worked on the Blue Ridge Parkway project and who was directly responsible for the master plans and the construction of the segregated recreation areas along the parkway, such as Pine Spur and other sites. Often those charged with the oversight of WPA programs or construction of facilities for negroes were themselves, of color. It is not known whether Robert G. Hall was black, but it is of little consequence as the segregation was well defined by the literature. Segregated picnic areas, signs in restrooms, limited motel accommodations, and other clear obstacles to travel prevented extended use of the Parkway by African Americans in its early history. Just how many African Americans worked directly in the construction of the Blue Ridge Parkway is not known. The construction of the Parkway was given over to private contractors and the records were never systematically gathered and preserved. Some letters have survived from other WPA parkway projects and they seem to indicate that African Americans were given construction work, but that racial strife was an issue among the workmen. Even when people of color could get hired on WPA projects or in CCC camps, the going was not easy. For example one letter from a workman on a parkway project in Chicago complained to Harry Hopkins, the Director of the WPA regarding a work program on the Chicago 56th and So. Parkway, describes the segregation of the work-force on his project in 1936. (McElvaine, p.89 ) |

|

The Civilian Conservation Corps camps along the parkway at the various identified locations, appear to have answered to one central Civilian Conservation Corps camp, near Galax, Virginia, Camp NP-29 , a camp that has left few documents for historians. The details of these camps is covered in the excellent study of the CCC by local historian Harley Jolley, The CCC in the Smokies (2001) While the disposable income of African Americans had expanded between the wars, few urban African Americans could afford the cost of personal automobiles, nor were they inclined to look toward the Parkway as a tourist destination. Yet, African Americans were highly mobile and the tourist market in that cultural sector was not lost on the planners of the parkway. African Americans were planned for by those charged with the construction of the Parkway and several recreation areas were developed to 'accommodate' a small number of segregated camping and picnicking areas. The segregated bathrooms that were present for many years all along the parkway often appear in apocryphal literature, but scarce information supports actual segregation of restroom facilities. There is clear indication, however that signage directed users to black and white stalls. Planning documents contain only evidence of tenuous commitment to the African American parkway traveler, but it was far more commitment to integration than was found in the public at large. While the planned segregated recreation areas reflect the cultural patterns of legal segregation reinforced by custom and the extra-legal oppression seen throughout the South in the 1930's and 40's , the remarkable point is the hyper-sensitivity to racial difference seen at the government level by planners in both the shabby construction, the sheer paucity of accommodation, and the failure to follow through with planned facilities. The Pine Spur recreation area in Virginia was the largest recreation area planned specifically for African Americans on the parkway. It was located at milepost 144 just south of Roanoke but was not put under construction until 1941. There is evidence that other recreation areas for African Americans were planned but the war effort stopped all construction on the parkway and the Pine Spur recreation site was never finished or opened. The Roosevelt administration was far better than previous administrations. He and his Cabinet members attempted to bring minority appointees into New Deal agencies and projects, however, those who were hired were largely placed in the agencies to work as "advisers on Negro affairs." They were given positions in order to provide advice on racial issues or to head specific segregated programs often entitled Negro divisions. While many of these positions were titular with little real power, the positioning of African Americans in administrative positions was the beginning of many important social and economic changes for this population. Even though legislation discriminated against the lower paying service jobs, such as those along the Blue Ridge Parkway, Roosevelt's popularity with blacks went up significantly from the previous administration and there was a steady migration from the party of Lincoln to the party of Roosevelt --- obviously an intended result. As more elite and educated African Americans were brought into administrative roles in the New Deal program, the more their decision making shaped the foundation of the urban renewal process. It was this core elite that were often called on to make decisions regarding what slums and blighted areas to be removed from their administered communities. It was these bright and eager leaders who were called upon to make decisions on clearing urban areas and on where the cleared populations were to be re-settled or where housing projects were to be built. Unfortunately the efforts of these African American administrators were compromised by the poor results of these massive urban renewals which too often fragmented or fractured the cohesion of communities and marginalized whole neighborhoods. Leadership opportunities soon became liabilities. Opportunity for African Americans in the New Deal was a paradox and it was played out in cities throughout the south, including Asheville and other North Carolina cities. |

|

|

While there are numerous accounts of the activities of the men who legislated, designed, and built the Blue Ridge Parkway as well as other New Deal projects, there are few recorded accounts of women whose work is associated with the National Parks in the southeast, unless one looks to the Appalachian arts and crafts industries or to environmental activists. Generally, men held most of the power in their administrative roles in planning and execution of the parkway. They certainly dominated engineering and architectural landscaping. Those men who labored on the actual building of the parkway shared that work with African Americans and other minorities, but not women. While the stigma of doing work, road work, that had once been the domain of the Negro did not seem to deter those men who were desperate for work, it is rare to find a man doing "women's work" during the years of the Great Depression. The assault on self-esteem was, evidently, too great to be caught doing the jobs of women. Further, during the depression years, only one member of a household was eligible to qualify for a relief job. If a woman was single or could prove that they were the economic head of the household, they could then be hired. If they could not prove eligibility and/or they had a physically able head-of-household husband, they were out of luck --- out of a job. As a back-lash to immigration, the state maximum hours laws reduced the employment of women starting in the 1920's and many women found employment very difficult during the economic depression of the 1930's though remarkably over 24 percent of women were employed in 1930 according to the census and in 1940, some 25.4 percent were gainfully employed. Domestic services, clerical workers and factories employed the majority of women. In the 1930s women entered the workforce at twice the rate of men but they were salaried substantially lower than men. The average annual salary of a woman in 1937 was $525, according to the Social Security Administration. Of the 4 million individuals hired by the New Deal program, CWA (Civilain Works Administration), only 300,000 were women and most CWA jobs were seen as not "suitable" for women. One area of the economy did benefit women and this was travel and tourism. Many women were engaged in the craft industry and many more, particularly African American women were employed as domestics for both the "summer people" and the large hotels. Many African American women benefited from the incomes of their husbands who held good employment as Pullman Porters on the railway. |

|

|

|

|

|

A very poignant letter written by a woman from the Buncombe County Jail in February 1934, graphically characterizes the plight of women during the depression if they were both poor and colored in North Carolina. The woman in this letter writes a pleading letter to "President Hoover," in confusion, not knowing, that Roosevelt had been in office since 1933.

|

|

|

|

|

|

When Fred Bauer, Vice-Chief of the Eastern Band of the Cherokee testified before the House Committee on Public Land regarding the so-called Weaver Bill ("Establishing the Blue Ridge Parkway,") he bitterly said that the government was trying to "landscape the Indians into the park entrance ... for the entertainment of rubber-necked tourists." This acrimonious outburst by Bauer at the Congressional hearing, is one of many such desperate word-storms levied against the government for their handling of right-of-way issues for the closing segment of the Blue Ridge Parkway planned to run through the Qualla Boundary and to end at Oconaluftee on the Cherokee Reservation. Bauer and his wife Catherine were two of the most outspoken opponents of the government plan and their campaign against the parkway and the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) became so strident that George Stephens, the owner of the Asheville Citizen and the Times, sent a notice to his paper and to others to not print anything the Bauer's sent to the paper. There is evidence that the Raleigh News and Observer and the Charlotte Observer took the advice of Stephens ... (so much for the 'free' press!). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

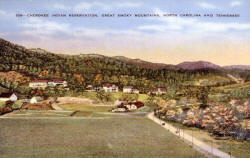

The burning question with the Qualla Boundary and the construction of the last leg of the Blue Ridge as it ended at the doorway to the Smoky Mountains National Park, was not one question, but many. Whose interests did the parkway serve? Whose parkway would it be when completed? Was the parkway even necessary? The attempts at answering these questions brought to the front of the debate all the well-known cultural and class conflict debates. Negotiations began with the Cherokee in the mid-thirties but it was not until 1940 that the tribal council reluctantly approved the route for the parkway to pass through their territory and granted the right-of-way for the construction of this last leg of the North Carolina route through the Cherokee Reservation. The Qualla Boundary, centered in Jackson and Swain Counties is geographically the North Carolina doorway to the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The Park which surrounds the Cherokee Reservation on three sides, was newly created in the 1930's and is positioned at the edge of the two competitive states that had interests in claiming the Cherokee. The Qualla Boundary could also be seen as sandwiched between the two large and often competing park systems; the Blue Ridge Parkway and the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The lessons in travel and tourism learned from their Government neighbors gave the Cherokee the opportunity to develop their own travel and tourism industry. Tourism was the economic future for the Cherokee. On this fact all parties in the geographic area were agreed. On most other facts, there was disagreement. While there was a clear need to generate an income to sustain the some 2200 Cherokee who were living in the Qualla Boundary in the 1930's, the means of income-generation was in dispute. How to maintain their identity and their traditional way of life with so many new encroachments became one of the most compelling conundrums for the Eastern Band of the Cherokee. Since the 1830's, when the tragic Trail of Tears removal program decimated the eastern Cherokee's way of life, the tribe struggled to reorganize and find their place again in the mountains of western North Carolina. Following removal the tribe managed to negotiate the purchase of some 60,000 acres of land and a charter that legalized their status as a Cherokee tribe. They succeeded and established a Tribal Council that would guide their people. The charter they had negotiated with the state of North Carolina defined them as a corporation yet their status as an Indian tribe placed them under the jurisdiction of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). The struggle between state and federal agencies put a strain on the already fragile fabric of the tribe during the Blue Ridge Parkway debate as some in the tribe aligned with the state and others with the BIA and the federal government. The Indian New Deal was enacted through the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934. The newly appointed Commissioner was John Collier. Also called the Wheeler-Howard Act, the IRA was the result of Collier's regionalist vision. The so-called "regionalist vision" of Collier was actually part of what was referred to as the "regionalist movement." Those who subscribed to this movement believed that America needed to be saved from the rapid industrialization seen in the 1920's and 1930's and that this could be accomplished by going back to regional values and life-styles. 'Regionalism' was a romantic notion that pushed for rejuvenation of art and craft as well as preservation of wilderness and the preservation of what was believed to be the rapid disintegration of unique and native cultures such as the Native American. and the Appalachian mountaineer. |

|

|

In many ways the issues of the Appalachian mountain people who lived along the course of the Blue Ridge Parkway was similar to that of the Cherokee. The people were self-sufficient and made a living off the land. They liked their isolation and prided themselves in their self-sufficiency. Again, the interview of Mary Jones by Dr. Louis Silveri captures the life-style of the families in rural Ashe County and the changes that were brought into the area with the WPA work programs of the New Deal. For example, when the CCC came to the area to work on the Parkway and on other WPA projects not all the families welcomed the new jobs and income. Mary Jones describes the work of the New Deal in Ashe County.

|

|

|

Like the Cherokee, the local mountaineers were also exploited by tourism, but in both cases the exploitation was often mutually agreed upon. Money is very persuasive. One of the methods for earning money for the mountain house-hold was to become part of what is known as the "cottage industry." This industry, which had its roots in the Arts and Crafts Movement and also in the rural settlement movement, allowed women to work in their homes, but to sell their products to local hotels, and other craft wholesales operations. Today, many question this home craft and have come to refer to the cottage industry as nothing more than a rural "sweat-shop" operation. Yet, many who participated in these home craft industries saw it differently and the money earned from their crafts kept many families from severe hardships during the depression years. Recent scholarship, however, continues to call into question the local memory of these home craft enterprises. Whether the cottage industries provided a benefit for the people of the region, or whether they were simply "sweatshops" that exploited cheap labor and hawked a pseudo-authentic product may not be an easy question to answer, as the industries varied so widely, as did their outcomes. There is no debate that the items offered for sale along the Parkway and in the urban centers near the Parkway, were popular, but the main center that was proposed for this regional craft never became fully operational and the sustainability was never put to the test until the creation of the Southern Highland Craft Guild was built just off the Parkway. The Guild has expanded the definition of "craft" and today tmany items have found their way into the Parkway shop that likely would have been excluded from the earlier Moses Cone site. |

|

|

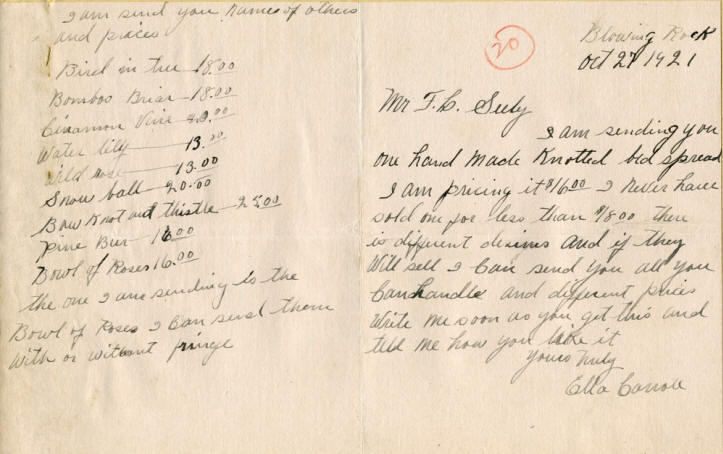

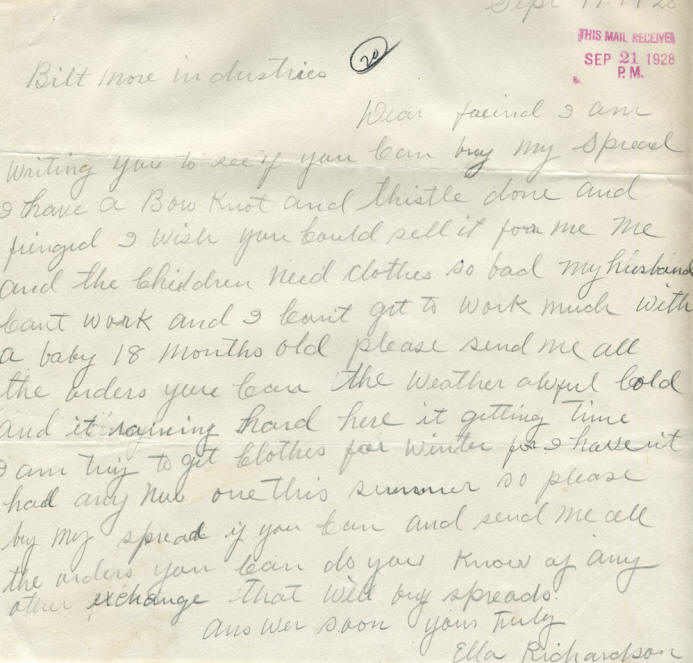

Perhaps the craft industry can be understood more clearly through the life of one woman who lived in the Boone area and who made tufted bedspreads for the Asheville Grove Park Inn in the early 1920's. We know a great deal about her through her letters which she sent to the Inn during the early years leading up to the depression. In these letters she guards her craft closely and in many cases desperately, as she struggles to make a life from the small income of her craft. She begins as a young and eager crafter, an unmarried girl, then marries, has a child and then struggles to care for the child and an invalid husband. Her story, gathered from her letters graphically details the life of one cottage industry worker and helps to put the lives of these workers in perspective. A sample letter is found below:

By 1929 she was becoming desperate:

|

|

|

Tufted bedspreads, runners, baskets, hooked rugs, pottery, weaving, Appalachian art and craft was proposed from the beginning of the Parkway to be a primary draw for the tourist and traveler. The donation of the Moses Cone property on the Parkway was proposed to be a craft complex that would be run by the well-respected Penland School, long a center of Appalachian craft. It was planned that it would highlight many of the mountain crafts and the park service would develop standards that would govern the quality and the boundaries of that mountain craft. For example, it was intended that true crafts such as basketry, weaving, wood-carving, and furniture, be separated from more commercial "knick-knacks" and that these generic tourist items be limited in any sales shop along the Parkway. The tufted bedspreads made by Mrs. Richardson, while appealing to tourists, would likely not have been seen as a native craft. Cottage industries were established to supply the tourist craft shops and a "guild" system was established to provide "good" craft and to serve as a monitor for quality. |

|

|

|

|

|

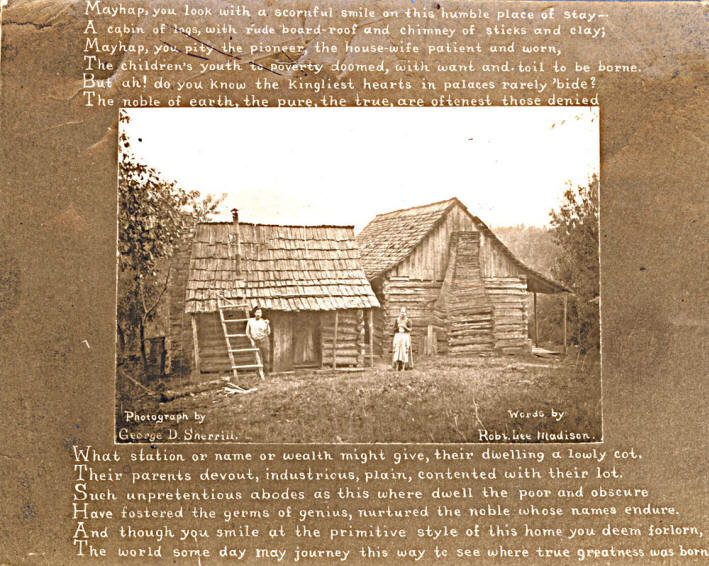

The pride of the mountain people can be seen in the poem that accompanies this photograph of a typical early mountain cabin. Written by Robert [?] Madison, the poem, while sentimental is tone, captures the feelings of many of the people who have lived in humble mountain dwellings, but have known the joys of the mountain life and the "genius" it can produce. This belief that mountain people had a special intelligence if they could only be brought into the mainstream, was a belief shared by many throughout the country. The idea that many of the founding fathers, and Lincoln, and Crockett, and others had come from humble beginnings but went on to greatness was and is promoted as a compelling American dream. If the muckrakers were convinced that graft and greed live in our American cities, the idealists were just as convinced that virtue lies in the hinterlands, in the 'back of beyond.' |

|

|

Authenticity is of major concern in evaluating the heritage sites along the Parkway and here, too, the Appalachian mountaineer has been largely misrepresented. Most of the "authentic" structures along the route were moved to the Parkway to provide context for interpretations of mountain life. The nostalgic recreations of life as it was lived along the Parkway, in the mountains of Virginia and North Carolina, was quickly adjusted to fit earlier generic stereotypes and the mountain dwellers along the path of the Parkway soon found themselves characterized as poor, moonshine-swigging, log-cabin dwelling, and illiterate people. Later attempts to ameliorate these views were only partially successful. The fascination with the moonshine history still seems to have a certain cache with tourists in the area. One can only puzzle about the recent beer-brewing frenzy in Asheville and find irony in these contemporary legal urban breweries. Has anyone considered brewing "white-lightening" in Asheville? "Moonshine City" of the U.S., anyone? |

|

|

|

|