The Indian Path in Buncombe County

|

|

|

|

|

| Title | The Indian Path in Buncombe County |

| Creator | Dr. Gail [Gaillard] Tennent |

| Identifier |

http://toto.lib.unca.edu/findingaids/books/booklets/indian_path_buncombe/ default_indian_path.htm |

| Subject Keyword : |

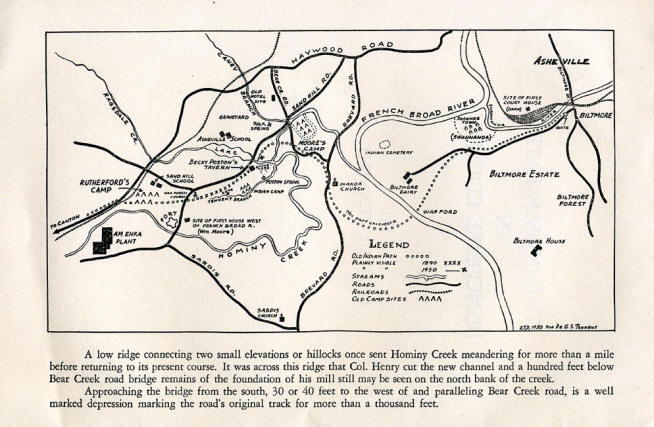

Dr. Gaillard Tennent ; Buncombe County, North Carolina ; Indians ; Cherokee ; Carolina Mountain Club ; trails ; Indian trails ; Indian paths ; Hominy Valley ; Dr. F.A. Sondley ; General Griffith Rutherford ; Biltmore Estate ; Brevard Road ; Sulpher Springs ; Sand Hill Road ; Ragsdale Creek ; Robert Henry ; Becky Poston's Tavern ; Oak Forest Church ; Hominy Creek ; Enka Road ; Captain William Moore ; David Gudger ; buffalo |

| Subject LCSH : |

Tennent, Gaillard S. (d. 1953) Indian trails -- United States Indian trails -- North Carolina Indians of North America -- North Carolina Buncombe County (N.C.) -- Description and travel Buncombe County (N.C.) -- History Indian trails -- Southern States |

| Description | A small 6 page booklet that describes the path taken by early Native Americans through Buncombe County, North Carolina from the time of the Spanish Conquistadors to the establishment of the city of Asheville, N.C.. |

| Publisher | Publisher: Stephens Press, Asheville, N.C., n.d. [after 1950 ?] ; Digital: D.H. Ramsey Library, Special Collections, University of North Carolina at Asheville 28804 |

| Contributor | |

| Date original | after 1950 |

| Date digtial | 2002-12-02 |

| Type | Text ; Map |

| Format | A 9.5" x 6.25", 6 p. booklet, privately printed |

| Source | F262 .B94 T4 ; 2nd copy in Carolina Mountain Club Archive misc. publications. |

| Language | English |

| Relation | Carolina Mountain Club Archive, D.H. Ramsey Library, UNCA ; |

| Coverage temporal | 1400's to 1800's. |

| Rights | No restrictions. Any display, publication, or public use must credit the D.H. Ramsey Library, Special Collections, University of North Carolina at Asheville. Copyright retained by the creators of certain items in the collection, or their descendents, as stipulated by United States copyright law. |

| Donor | n/a |

| Acquisition | n/a ;2002-12-13 [CMC copy] |

| Citation | "The Indian Path in Buncombe County," D.H. Ramsey Library, Special Collections, University of North Carolina at Asheville 28804. |

| Processed by | Special Collections staff, 2006. |